Flu's Seasonal Curve Swelled In 2017-18

The winter of 2017 and 2018 was a rough time to catch the flu or treat patients for it. Vaccines struggled to guard against the particularly aggressive H3N2 influenza subtype, while hospitals were facing shortages of some basic supplies even before dealing with a surge in flu-related hospitalizations. Given a nationwide spike in cases, public-health officials in Wisconsin shifted influenza surveillance into high gear. No one questions that the 2017-2018 flu season was tough, but how unusual was it really?

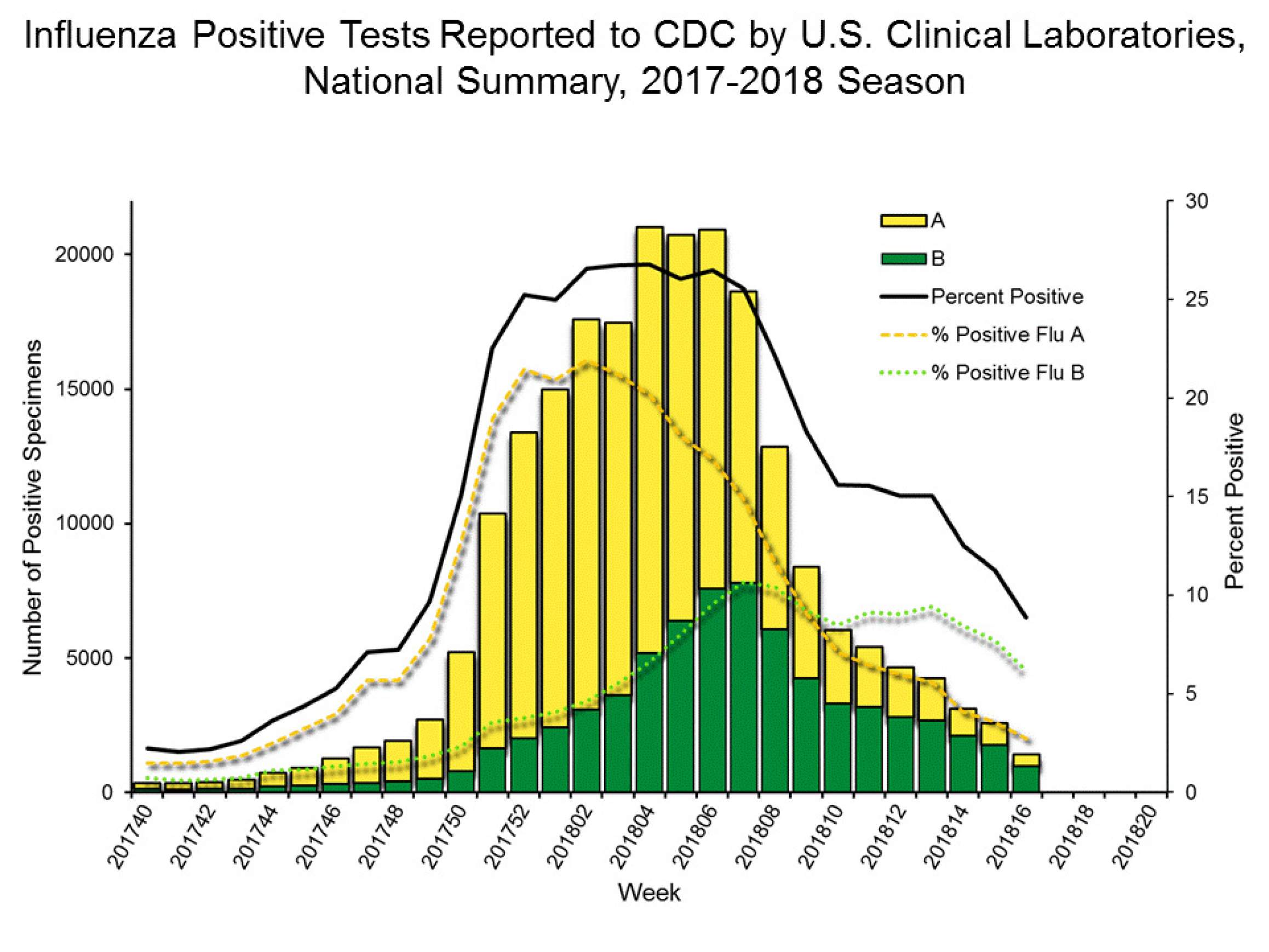

As cases gradually tapered off between late February and early April, the state-level data from the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene tell the story of a flu season that followed a familiar trajectory, but did so with a vaster scope. As in other flu seasons, this past one began to pick up steam in the fall, escalated sharply during December and January, then started to drop off gradually as spring (or what has passed for spring in 2018) approached. Influenza A cases dominated the first half of the season, with influenza B picking up steam toward the end but not enough to negate an overall decline.

The big difference in 2017-18 was that the peak was higher and lasted a bit longer, and the ensuing drop-off in cases wasn't quite so sheer. State officials even feared that influenza B cases would produce a second peak. Influenza B cases did indeed make the flu season longer and tougher overall, almost causing a brief plateau amid the overall decline in the spring. (There are four different types of influenza viruses, with A and B responsible for seasonal outbreaks in the United States.)

The overall scope of the season — measured in terms of hospitalizations, the amount of samples healthcare providers and public-health labs tested, and the number of patients who tested positive for flu viruses — is what makes it stand out. The patterns weren't abnormal — though public health officials stress that they don't believe there's such thing as a "typical" flu season — yet overall the outbreak was nearly as severe as the 2009 pandemic, said Pete Shult, director of state hygiene lab's communicable disease division.

"What was different is the magnitude of that epidemic peak, whether you're measuring the amount of testing what was being done, the amount of positives that were being seen, or some of the clinical and epidemiological indications," Shult said.

A lot of flu data about Wisconsin cases is available because the state hygiene lab draws on a statewide network of local public-health officials and laboratories affiliated with hospitals and other healthcare providers. The lab also gathers and tests influenza samples from clinical labs across a broad swath of the central United States, feeding that data into a federal surveillance network in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Federal funding helps the state lab pay for equipment and staff time to keep up with a surge in flu activity, but a season like 2017-2018 can strain overall efforts to track the flu, not to mention treat it.

"A lot of the clinical labs were experiencing sporadic shortages of testing reagents," said Erik Reisdorf, virology surveillance coordinator for the state hygiene lab.

"That's happened previously. It happened during the pandemic in 2009 for sure, but with the fact that the flu season was severe this year and also it tended to peak at very similar times across the country, some of the labs were having challenges getting the test kits."

Influenza never goes away entirely. Even through the summer, the state hygiene lab will typically learn of at least one or two cases per week. At that frequency, the disease is considered sporadic and doesn't pose much threat of contagion. But there's still an in-between realm, where flu isn't in full swing but still sickening enough people that there's a lingering threat of it flaring up, in a way that can be particularly dangerous for small children and elderly adults. That's where Wisconsin was by the end of April.

"As long as you have some measure of flu in the community, there's a chance it can get into a school setting or into a long-term care community and cause a problem there," Shult said.

What Wisconsin and North America experienced with influenza in 2017 and 2018 didn't break out of seasonal patterns to become a pandemic, but the familiar curve isn't necessarily reassuring in the bigger picture.

"I think this season in particular serves the purpose to show us that you don't have to have a pandemic to have a very impactful influenza season," Shult said.

From a global perspective, the U.S. and the United Kingdom had tough flu seasons, said Raina MacIntyre, a professor of global biosecurity at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Meanwhile, continental Europe had it easy while India is dealing with alarming annual flare-ups of the H1N1 virus, which caused the 2009 pandemic.

"In India, it has been causing very severe illness, with death rates more than 100 to 1000 times higher than elsewhere," MacIntyre said. "The pattern there is unusual and needs further study."

As for what Wisconsin and the U.S. as a whole experienced in 2017 and 2018, MacIntyre largely agrees with Shult and Reisdorf but still sees unusual features.

"It is correct that the epidemiology is similar in the sense that there was a typical epidemic curve with a peak in winter," she says. "However, there is still high flu activity in some states, such as California, and moderate activity in Wisconsin. This is not common so late in spring, but can occur. There was a lot of genetic diversity of the H3N2 circulating. It would be interesting to compare this with previous years over a decade or so."

Additionally, even pandemics have some things in common with seasonal flu outbreaks, but with far more brutal impact.

"Estimates of the 2009 pandemic suggest it was similar to a severe seasonal flu year in impact, although the average age of death was some 30 years younger than we see with seasonal flu — 53 compared to 83," MacIntyre said. "So we saw much younger people dying. The pattern in the 1918 pandemic also.showed young health adults dying. In seasonal flu the deaths tend to peak in the very young and the very old."