The Hazard Of COVID-19 Heading Up North For Summer

Every year, hundreds of thousands of cabins, cottages and lodges across the northern third of Wisconsin come back to life as their owners commence their annual summertime excursions to their home away from home. A majority are owned by people who live in the region, but one out of five of these owners live in the southern part of Wisconsin, and one in six hail from outside the state. Altogether, there are more than 200,000 second-homeowners in 21 northern counties who don't live there year round, and these families and their guests make a profound mark on the economy and culture of the region.

The sheer number of people who make their way to northern Wisconsin when the weather warms is a matter of serious concern during the COVID-19 pandemic. And as the days approach their longest and the stress of isolation mounts, the desire to head up north will become quite potent. On March 24, 2020, Vilas, Oneida and Bayfield counties issued advisories asking tourists and second homeowners to stay away during the COVID-19 health crisis to avoid spreading the virus.

Across the United States, local governments in popular tourist areas issued similar warnings. Though these actions were meant in part to slow the spread of COVID-19, they are also intended to protect rural areas that lack the needed medical resources to deal with even a limited outbreak of the disease.

For Wisconsin, cases of COVID-19 have been fairly limited in the northern rural counties over the first six weeks since outbreaks started growing rapidly around the state. As of May 21, 2020, 21 Northwoods counties accounted for 192 of Wisconsin's 13,885 confirmed cases and 6 of 487 confirmed deaths.

The warnings issued by local officials in northern Wisconsin highlight the unique relationship between locals and the typically urban-dwelling visitors from the south. After treaties between the federal government and the Ojibwe and Menominee nations in 1836, 1837 and 1842 opened the region to colonization and industrial development, economic activities expanded to include large-scale timber harvesting, mining, paper production and limited agriculture. As the 19th century ended, railroads marketed the rich natural landscape and tourist amenities to wealthy urbanites in collaboration with local governments and tourist promoters. And as the 20th century progressed, a growing middle class and the development of highways provided even greater access to the region.

These consistent interactions with the tourist landscapes by non-locals in northern Wisconsin transformed the Northwoods into a quintessential "pleasure periphery." Destinations like Hayward, Minocqua and Eagle River offer miles and miles of lakefront property, as well as ample access to hiking, cross-country skiing and snowmobiling. In areas that are fortunate to have a greater abundance of these recreational amenities, rustic cabins have given way to multi-million-dollar getaways.

While such patterns are plainly visible when driving through communities like Eagle River or Hayward, how much of Wisconsin's Northwoods is owned by non-locals and from where do they hail?

It's possible to answer this question given a change made to state law. Wisconsin's 2013-2015 biennial budget mandated local governments to coordinate with the Wisconsin State Cartographer's Office to develop a statewide database that provides digital access to information about land ownership. The resulting database and map provides a large set of data including (but not limited to) the tax mailing address of parcel owners, as well as the size, location and value of individual parcels. More than 3.4 million parcels across Wisconsin are included in this database.

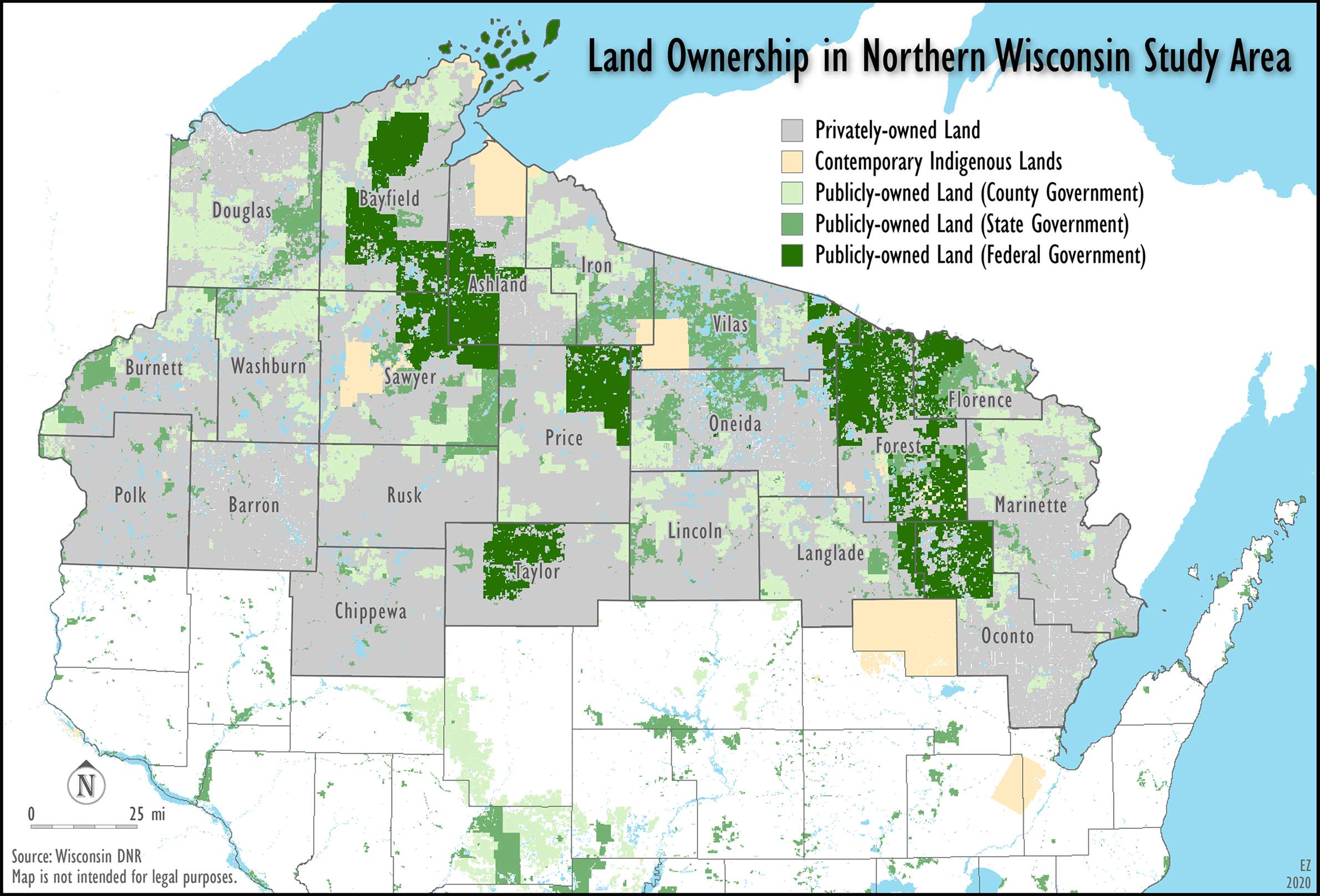

Tax mailing addresses can help to gauge ownership patterns in 21 northern Wisconsin counties, which can be visualized using a geographic information system. These counties are Ashland, Barron, Bayfield, Burnett, Chippewa, Douglas, Florence, Forest, Iron, Langlade, Lincoln, Marinette, Oconto, Oneida, Polk, Price, Rusk, Sawyer, Taylor, Vilas and Washburn.

The 21-county area covers 21,000 square miles, of which 36% are public lands (local, state, and federal) and 64% privately owned. Thousands of parcels are owned by corporations such as Georgia-Pacific and Enbridge, and are used for logging and pipelines, respectively. There are 718,808 privately owned parcels, of which most are owned by individuals as either permanent or seasonal residences.

Property owners can be divided into three categories: local permanent residents, non-local Wisconsin residents and out-of-state residents. As of 2018, 58.4% (419,583) of the parcel owners were local to northern Wisconsin, 19.5% (140,105) identified as non-local property owners who live elsewhere in the state, and 16.6% (119,442) were from out-of-state. Meanwhile, 5.5% (39,678) of parcels were additional properties owned by residents of the region, such as a permanent resident of Rhinelander owning a parcel of lakefront property in Vilas County.

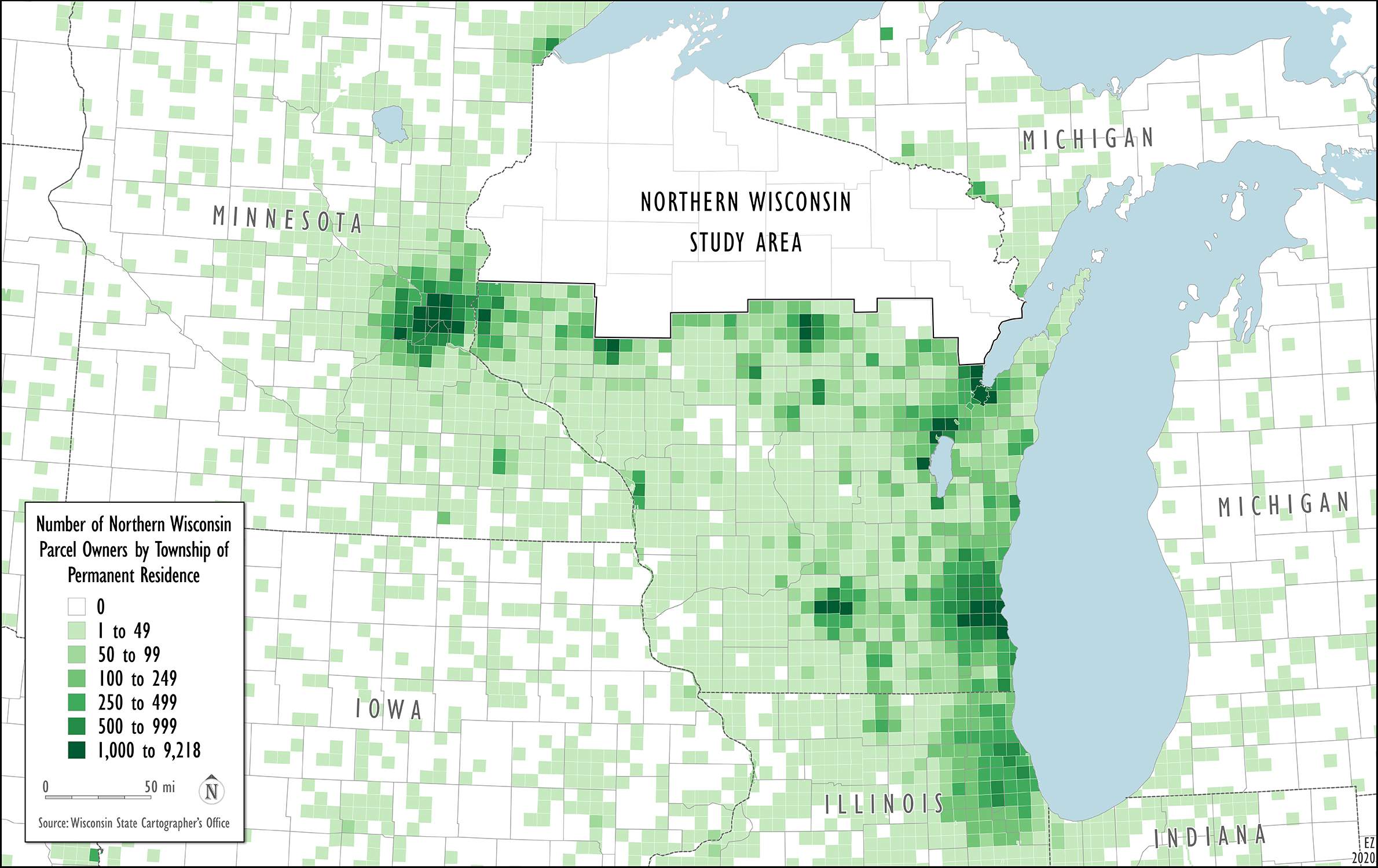

Of the non-local Wisconsin property owners, 42% (59,893) came from the counties immediately south of the study area, and 34% (47,677) were from the metropolitan areas around Madison and Milwaukee. The remaining 23% (32,535) came from elsewhere in southern Wisconsin.

Local property tax bills for Wisconsin lands are sent to owners in all 50 states, three U.S. territories and 25 foreign nations. Minnesota residents comprise the largest out-of-state block of Wisconsin property owners (37,918), with the vast majority of them living in the Twin Cities metropolitan area (35,756). Illinois residents made up the second largest group of out-of-state owners at 20.6% (24,536) with most coming from the Chicago metropolitan area (21,575). Other states hosting noteworthy numbers of residents with Northwoods connections include the seasonal snowbird destinations of Florida (4,149), Texas (2,977), California (2,593) and Arizona (1,635).

Altogether, non-local property owners are concentrated in southern Wisconsin, Chicagoland and the Twin Cities. Minnesotans are more likely to own property in northwestern Wisconsin, while southern Wisconsinites and Illinois residents are more likely to own property in the north central and northeastern parts of the state.

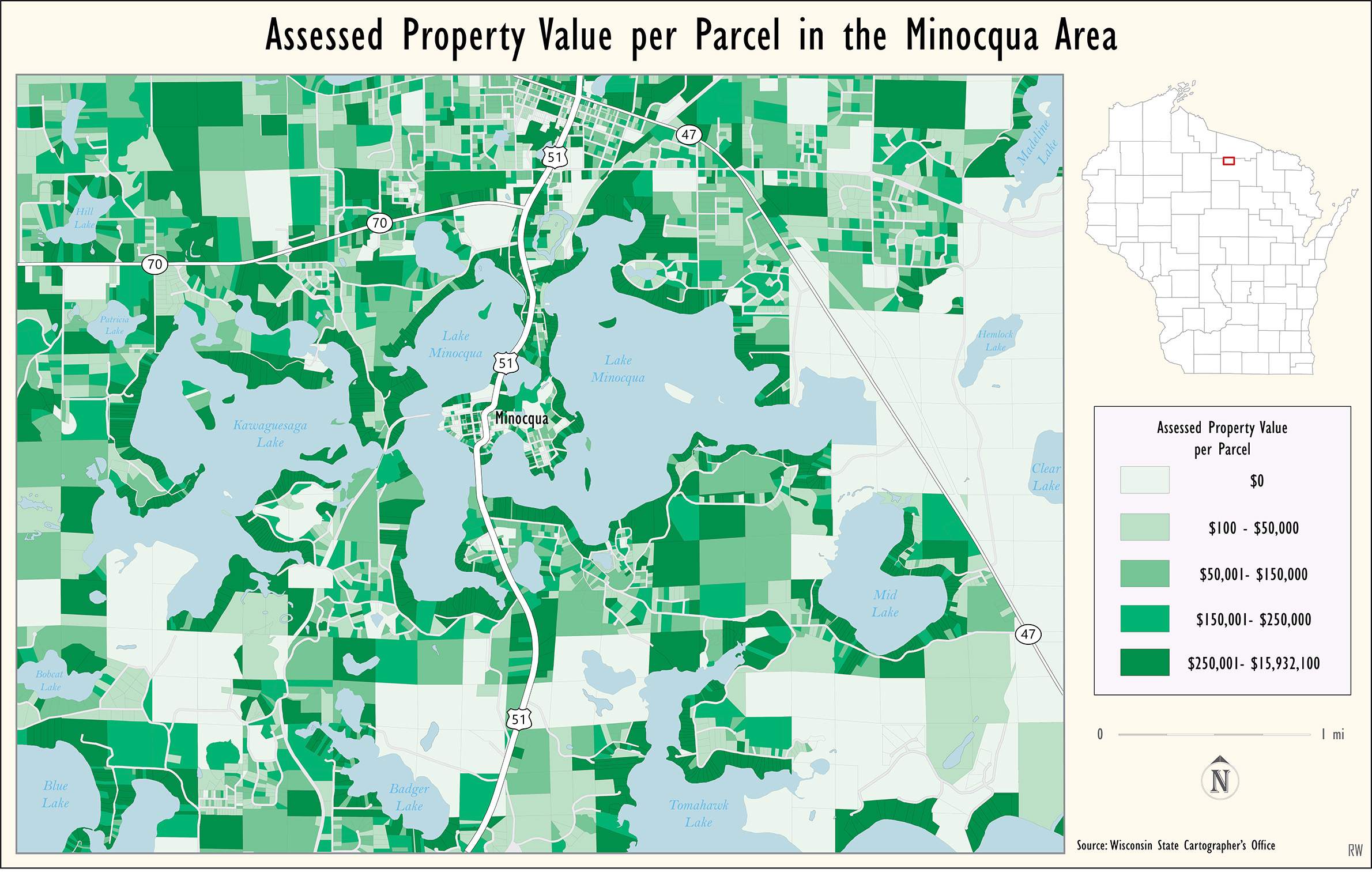

The average size of parcel ownership and the assessed value of parcels shows stark differences between local and non-local owners. For local owners, the average parcel size is17.1 acres with an average assessed value of $93,428. For other Wisconsinites, the size increases to 18.4 acres, as does the value at $95,408. Meanwhile, for out-of-state owners, the size of the parcel decreases to 16.2 acres, but the value increased to $123,501, an increase of nearly a third.

Property values and ownership varies across northern Wisconsin, with higher property values located near larger communities and along bodies of water, as well as near highways. A map of property values near Minocqua illustrates how property values are much higher along the surrounding chain-of lakes, with almost all properties valued over the $250,000 mark. The most expensive property, at $15 million, is a Walmart, but there are several other properties over the million-dollar mark throughout the area.

Due to the higher property values along bodies of water, some local areas benefit more than others. This pattern stands out when analyzing the impact of second-home ownership on funding for local school districts. Districts with higher rates of second homeowners have a much larger tax base compared to those that don't. While this is an obvious benefit for local owners and their children, it can also put local officials in a bind when they are lobbied to keep tax rates low to appease non-local property owners.

This tension is true for the Northland Pines School District, which benefits greatly from the property ownership of non-locals around Eagle River. With a student population of only 1,300, the district draws in nearly $20 million in tax revenue, which results in it having one of the lowest mill rates (5.88 per $1,000) in the state. This funding level equates to approximately $14,000 per student.

In comparison, the Hurley School District, located to the northwest of Northland Pines, can only cover about $6,000 for each of its 562 students, as this area in Iron County does not offer the same amount of lakefront property and commensurate tourist amenities.

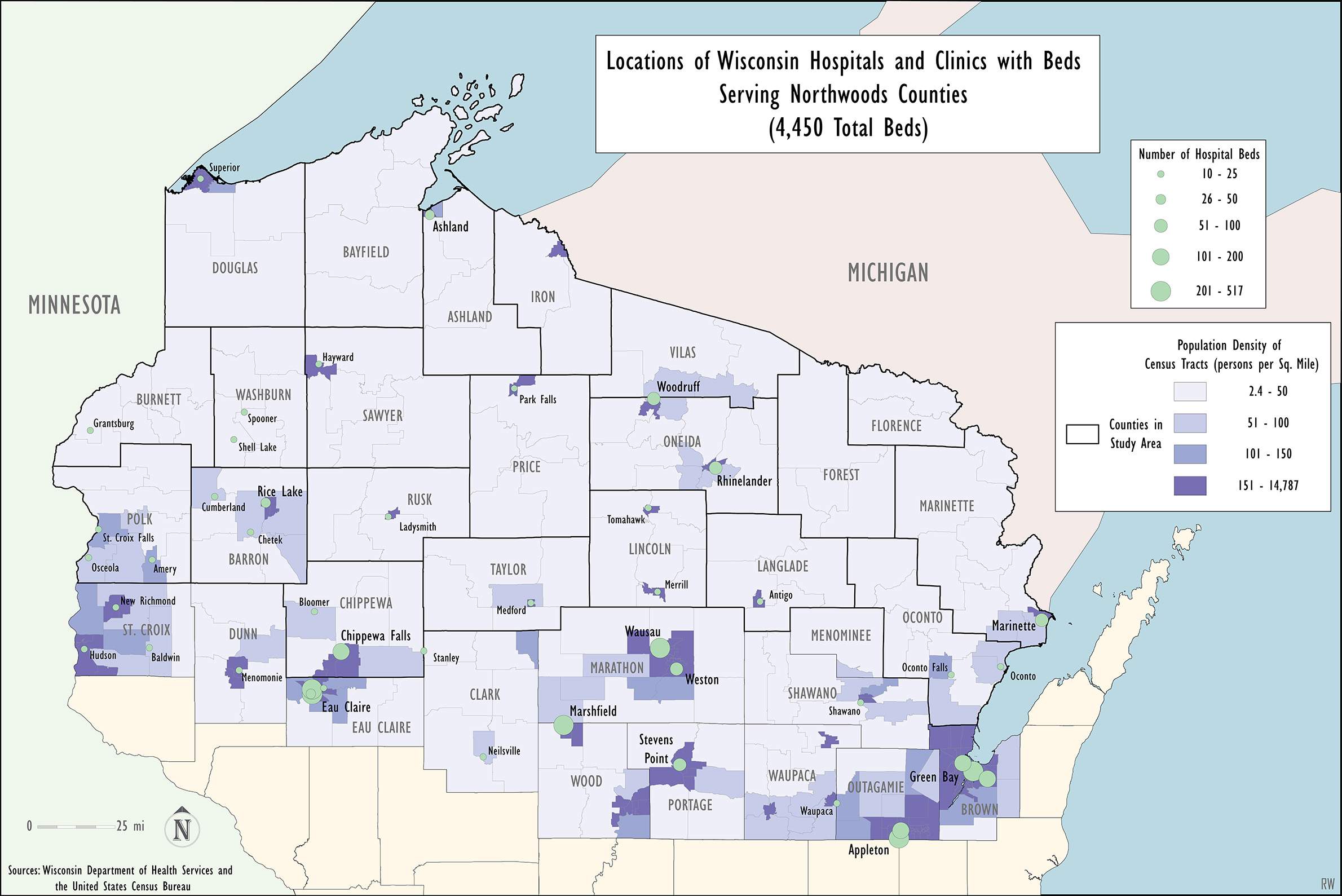

Though over half of the Northwoods is owned by locals, the economic impacts of non-local ownership and tourism demonstrates the magnitude of statements by local officials who have told second homeowners to stay at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Milwaukee, Chicago and the Twin Cities each had high rates of COVID-19 by May 2020. If non-local homeowners travel in large numbers to northern Wisconsin during the summer and local outbreaks of COVID-19 emerge, would hospitals in the region be able to handle a growing number of patients?

According to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, northern Wisconsin does not have a large hospital capacity. With the exception of Woodruff, Rhinelander and Marinette, many local medical centers have 25 or fewer beds, and are likely unable to provide intensive care treatments needed by the most critical COVID-19 patients. Larger medical facilities are found along the southern fringes of the region in Eau Claire, Marshfield, Wausau and Green Bay. Therefore, a growing outbreak of COVID-19 in the Northwoods would threaten the limited medical capacities in the region.

For seven weeks, starting on March 25, all 72 counties in Wisconsin were covered under public health orders issued by the administration of Gov. Tony Evers and the state Department of Health Services, intended to limit movement and gatherings that would facilitate the spread of COVID-19. Those restrictions were lifted when the state Supreme Court struck down the order on May 13, limiting any future statewide approach through a rulesmaking process involving the Wisconsin Legislature.

Following the court decision, county and municipal public health departments in multiple heavily populated communities in southern and eastern Wisconsin issued local stay-at-home orders. However, this action was not taken in counties across much of northern Wisconsin.

Cabins, vacation homes, summer cottages, or whatever one happens to call these getaways are central to tourism across the upper Midwest. While every vacation has its own unique story to tell, the realities of COVID-19 have placed local officials in the difficult position of weighing the economic lifeblood of tourism and the health of locals. The region lacks the necessary medical facilities to deal with a large-scale outbreak.

Over the first several months of the pandemic, Wisconsin's Northwoods has avoided an unmanageable number of COVID-19 cases. With summer arriving, though, the start of the tourism season and return of second homeowners to the region represents an uncertain variable for any future waves of infections.

This research was made possible with funding support from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Office of Research and Sponsored Programs. Students Zach Fisher, Andrew Moen, Hannah Wirth and Nicholas Berg contributed to this research.