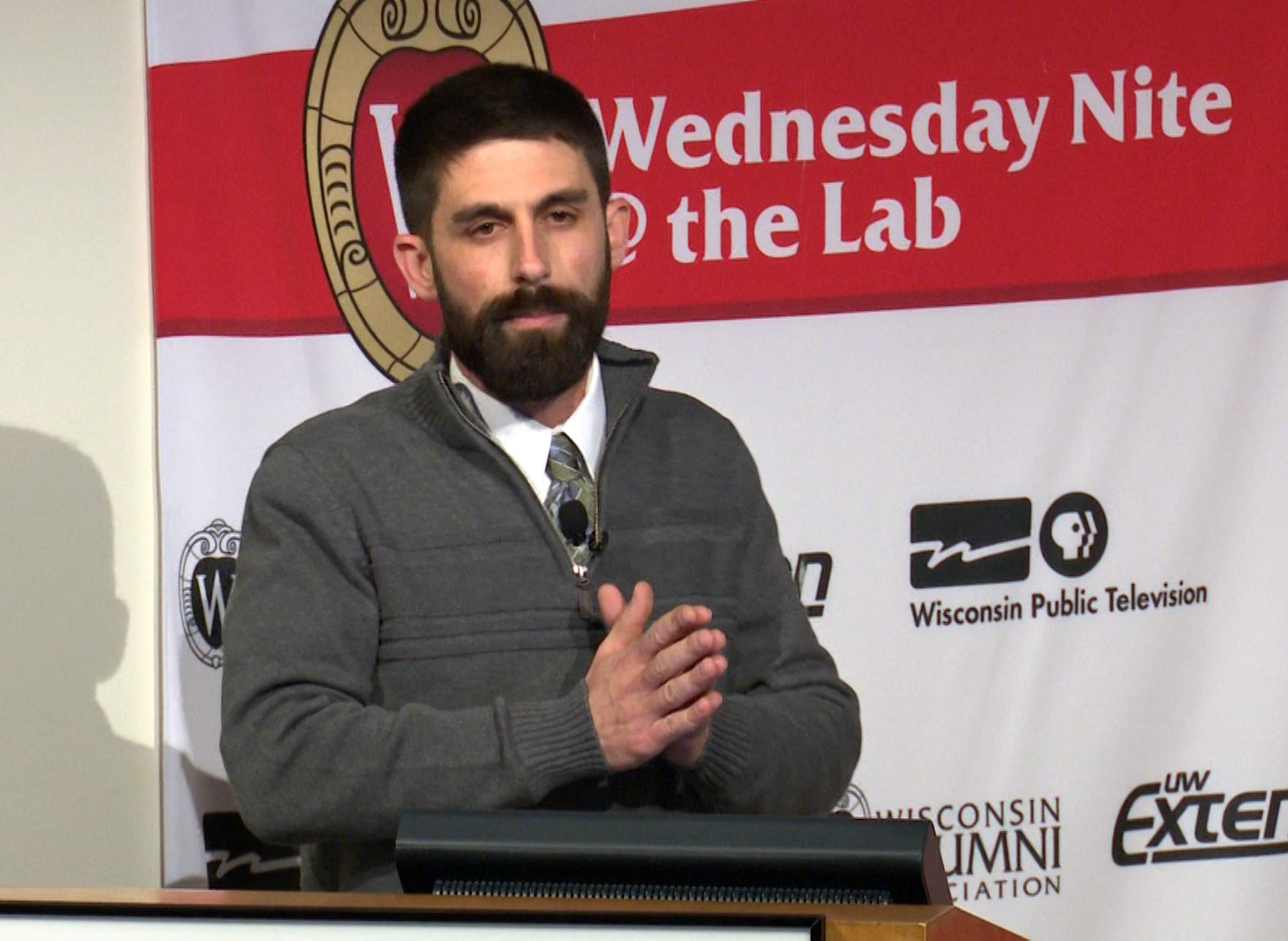

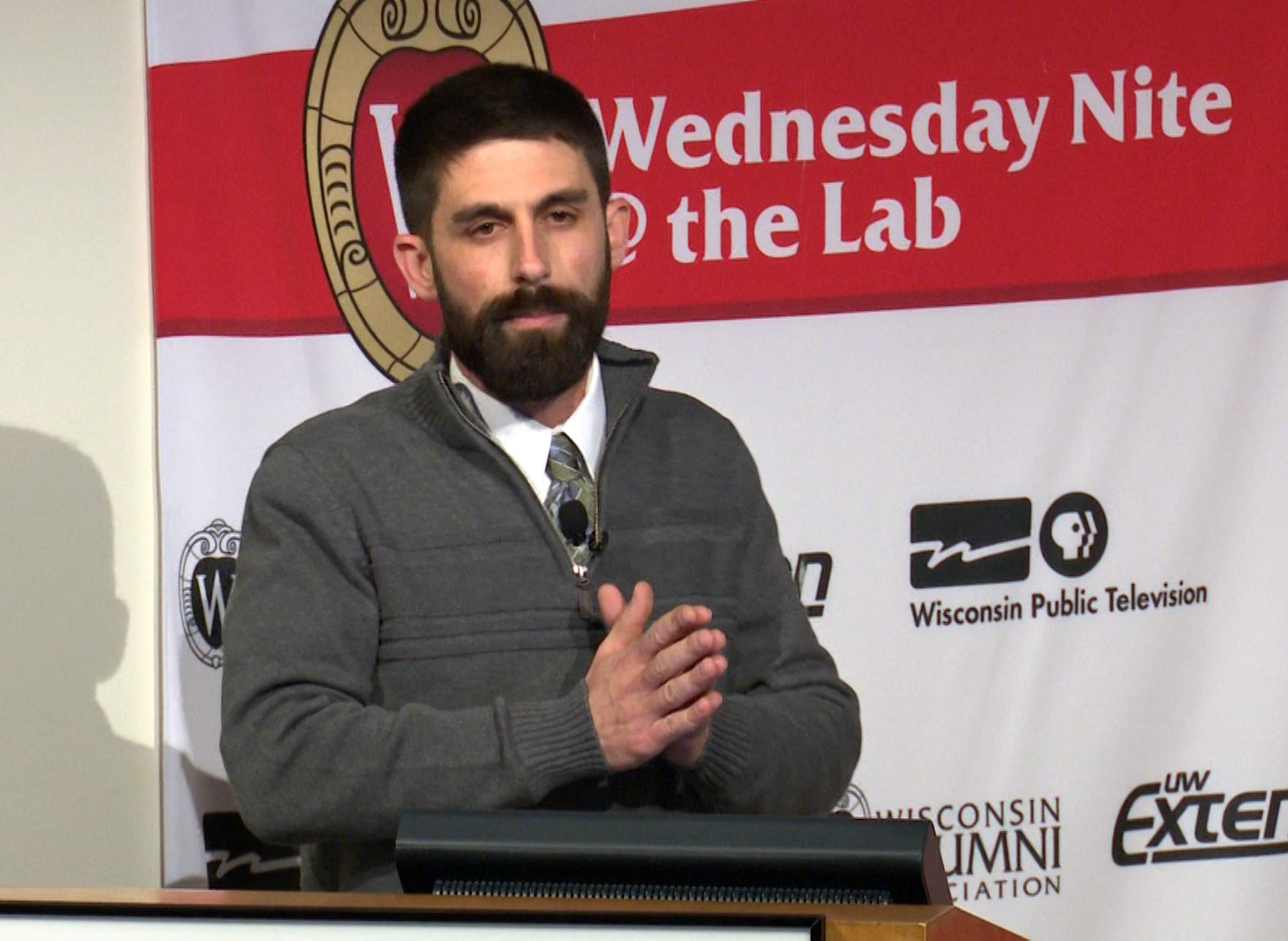

UW-Extension groundwater education specialist Kevin Masarik: "The thing that makes it difficult is it’s a critical resource for agriculture."

UW-Extension groundwater education specialist Kevin Masarik: "The thing that makes it difficult is it’s a critical resource for agriculture."

U.S. farmers embraced nitrogen-based fertilizer at a dramatic pace during the 1960s and '70s. Since then, its use has played a key role in boosting agricultural productivity. But as a consequence, nitrogen's more soluble form, nitrate, has become a common drinking water contaminant in Wisconsin and around the country.

In a Jan. 20, 2016, talk at the Wednesday Nite @ The Lab series on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, UW-Extension groundwater education specialist Kevin Masarik laid out the agricultural context in which nitrate is used and explained how it often can end up contaminating some of Wisconsin's drinking water. The talk was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place.

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for most plants, and therefore nitrate will continue to play an integral role in agriculture, Masarik said. But Wisconsin's varied bedrock geology and the specific choices farmers make about applying nitrate play a big role in determining how much of it actually ends up in the water supply, he explained. Nitrate contamination can present a serious public health threat, especially in the form of methemoglobinemia, colloquially called blue baby syndrome.

In his talk, Masarik outlined what Wisconsinites can do to protect their drinking water, including testing private wells and looking up information on the Well Water Quality Viewer, developed by the Center for Watershed Science and Education (a partnership between UW-Extension and UW-Stevens Point's College of Natural Resources).

Masarik also discussed some of the solutions he and other Wisconsin water quality experts have proposed. If farmers introduced different kinds of crop rotations, grew cover crops and implemented other land-use practices — and if those practices become economically viable — he said Wisconsin could vastly improve its nitrate picture.

Masarik also shared his advice for private well owners in a recent online Q&A.

Key facts

Key statements