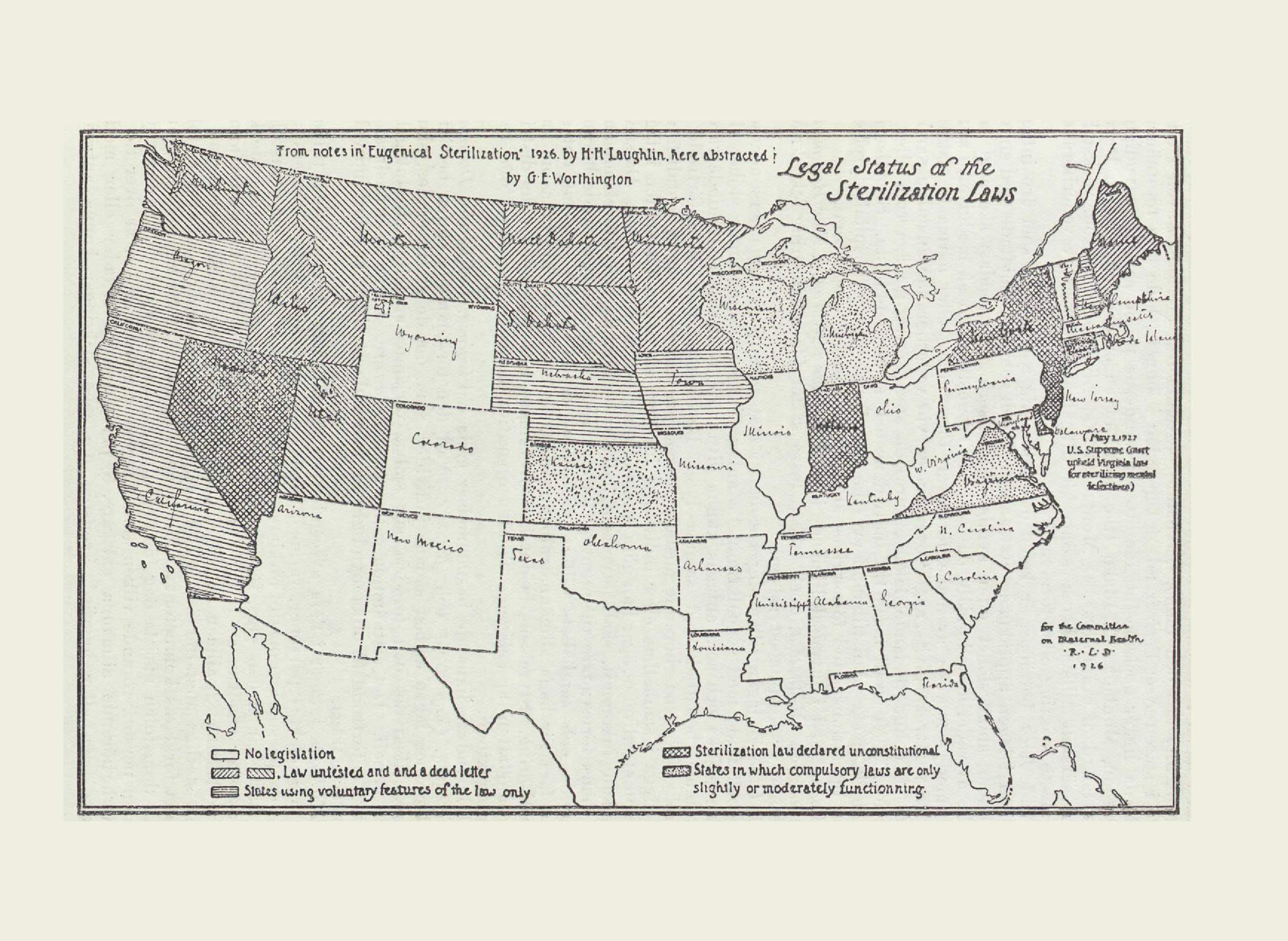

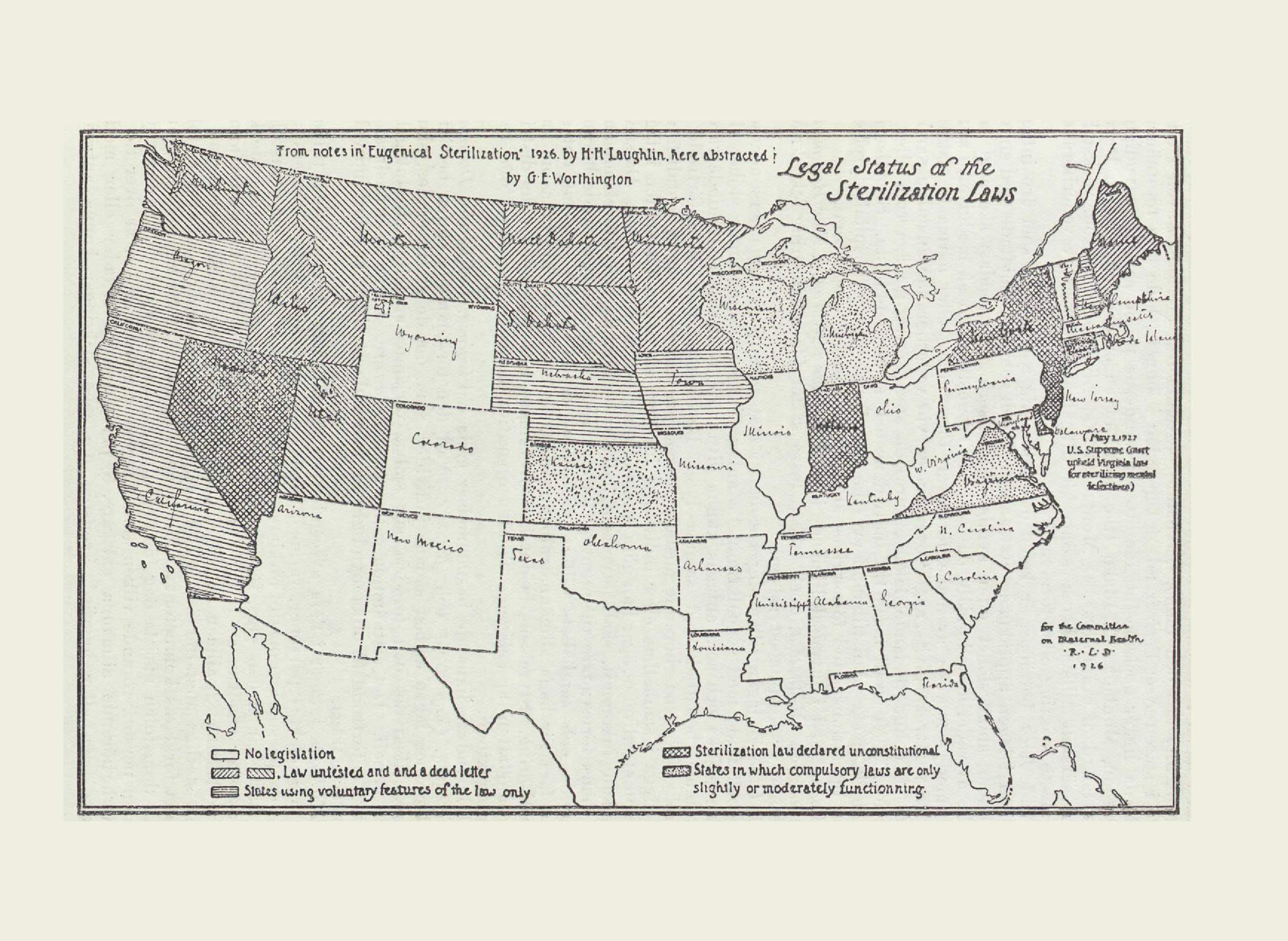

A 1929 map created by the Swedish government documents the widespread use of eugenics-motivated sterilization in the United States.

A 1929 map created by the Swedish government documents the widespread use of eugenics-motivated sterilization in the United States.

Policies based on eugenics — the notion that humanity can essentially speed up its own evolution by weeding out people with "undesirable" traits — were once widespread in the United States. Eugenics became established as a respectable scientific field in the late 19th century, and had broad support among social and economic leaders, politicians and advocates for women's suffrage. The eugenics movement in the U.S. informed federal immigration restrictions and influenced forced-sterilization laws in at least 30 states.

The Nazis' use of eugenics, while influenced by American policies, eroded public support for the idea in the United States after World War II. But the legacy of eugenics continued to harm vulnerable populations in the form of forced sterilization into the 1960s and 1970s.

Wisconsin had its own role to play in the eugenics movement. Phyllis Reske, a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee's College of Letters and Science, discussed the state's eugenics program in a January 21, 2016, interview for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place. Reske wrote a 2013 journal article detailing Wisconsin's forced sterilization of women, titled "Policing The 'Wayward Woman.'"

In the interview, she detailed how eugenics resonated with the politics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. People who violated the social mores of the times often were targeted for sterilization, and industrialists found that eugenics helped to deflect blame for poverty and other social ills away from capitalism and onto supposedly inferior genes. Reske detailed how Wisconsin's sterilization program had an outsized impact on women—and noted that, going back through the record, it's very hard to find evidence that anyone at the time listened to the voices of people being institutionalized.

Key facts

Key quotes