What Wisconsin's Special Elections Looked Like In 1963

How vacant state legislative seats get filled seems to have long been a hairy question — that is, when people think much about it at all.

By Scott Gordon

February 15, 2018

Low angle view of dais in Wisconsin Assembly chambers

How vacant state legislative seats get filled seems to have long been a hairy question — that is, when people think much about it at all. Wisconsin and most other states use special elections to fill a seat when a state legislator resigns or dies before the end of their elected term. Over the course of the state’s history, though, the rules governing special elections have been light on specifics, creating occasional controversy.

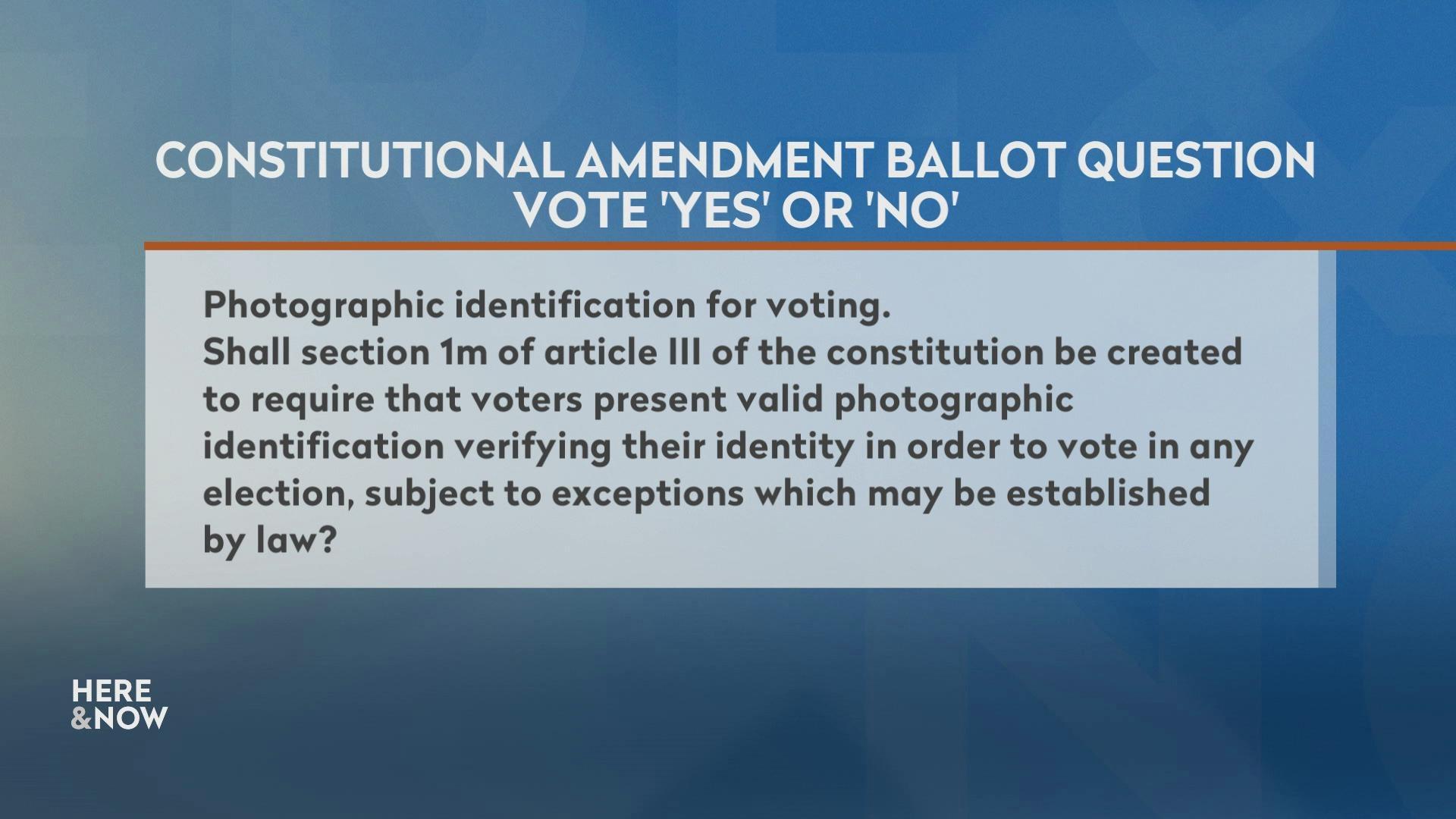

Gov. Scott Walker asserts that the wording of state law gives him considerable latitude to not call special electionsunder certain circumstances, namely for a pair of vacancies he created by hiring two state legislators to work in his administration. This law provides some guidance about how soon special elections should be called — but it uses broad language like “as promptly as possible,” and does not set firm time intervals or deadlines. Democrats in the Wisconsin Legislature are trying to change that with a bill (SB 782) that would require special elections to be called within 60 days of a vacancy, barring some other exceptions that the law provides, such as when one occurs close to an already scheduled spring or fall election.

The Democrats backing this bill — which is likely dead on arrival in the Republican-controlled legislature — aren’t the first to take issue with Wisconsin’s ambiguous vacancy rules. While investigating the past five decades of special elections in the state, WisContext uncovered a Legislative Reference Bureau research bulletin from 1963.

“Filling Legislative Vacancies: The Wisconsin Experience” contrasts how the state Constitution and statutes treated such vacancies, and delves into various facets of special elections up to that point in Wisconsin history. While it’s just a single report that’s more than a half-century old, it offers helpful clues into how Wisconsinites have thought about special elections.

The ways in which state Legislatures do business change over time.

According to the Legislative Reference Bureau report, Wisconsin held just 54 special elections for state legislative seats between 1848 and 1963. However, WisContext found 105 of them between 1971 and early 2018.

Perhaps this difference just means life moves faster now, or maybe it means that state legislators have become quicker at climbing the political ladder in recent decades. (Most vacancies since 1971 occurred because a legislator was elected or appointed to another post in state government.) The period when the Legislature is actually voting on bills is still mostly confined to a few months of the year, as it would have been in the 1960s, though a legislator is officially employed on a year-round basis: governors can call them back in special sessions, and officeholders do plenty of work outside of debating and voting, from studying issues through committees to assisting constituents. And in the contemporary landscape of politics and money, the interests of legislators to fundraise for reelection can be insatiable, even in state-level races.

Even in 1963, the author of “Filling Legislative Vacancies: The Wisconsin Experience” was feeling the world speed up, and suggested that laws addressing gubernatorial authority over special elections weren’t quite up to the task.

“In a simpler age when Legislatures met but a few months every 2 years, this method of filling legislative vacancies proved adequate. Now, with the Legislature meeting in lengthy special and extended regular sessions throughout much of recent legislative biennia, there are those who believe some modification, some modernization, should be made in the process of filling vacancies which arise in Wisconsin Legislature.”

Indeed, while some of the finer points of state law have changed, the underlying system of filling vacancies remains much the same in 2018. It’s laid out pretty plainly in the Wisconsin Constitution: “The governor shall issue writs of election to fill such vacanu00adcies as may occur in either house of the legislature,” reads Section 14, Article IV. But in granting the governor that authority, the Constitution doesn’t lay out when or how it should be exercised.

Not everything has changed in the Legislature, though.

The 1963 report discusses state Sen. Fred Risser, D-Madison, who was first elected to the Legislature in a 1962 special election and still represents Senate District 26.

The state Constitution and state law might clash.

The Legislative Reference Bureau report seemed a bit skeptical of the specifics that state law sets out around the Constitutional authority for Wisconsin’s governor to call special elections. The state Constitution says that the governor “shall” call elections to fill vacancies, but state law at the time indicated that “a special election shall not be held when the last regular session for a vacated term has ended, unless a special session is called.”

“Between the ‘shall’ and the ‘shall not’ exists a gap which Wisu00adconsin’s Governors have interpreted to mean ‘may,'” wrote the Legislative Reference Bureau’s Michael R. Vaughan. “In that period between the early and latter parts of a legislative biennium, they have exercised their own discretion in calling or not calling speu00adcial elections. This discretion is not clearly granted by the Conu00adstitution.”

The state statute (8.50) regulating special elections in 2018 provides much the same wiggle room. It states: “Any vacancy in the office of state senator or representative to the assembly occurring after the close of the last regular floorperiod of the legislature held during his or her term shall be filled only if a special session or extraordinary floorperiod of the legislature is called or a veto review period is scheduled during the remainder of the term. The special election to fill the vacancy shall be ordered, if possible, so the new member may participate in the special session or floorperiod.”

That wiggle room is key to one reason why Gov. Walker says it is not worth calling special elections to fill legislative vacancies in Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 — because even if he did, there’s almost no way the new officeholders could be sworn in before the Legislature wraps up its regular session of debating and voting for 2018. A special election can’t be held immediately — a governor has to call it, and then the vote must take place between 62 and 77 days later.

Walker also makes a hair-splitting argument that specific language in state statute allow him to not call special elections in these two cases. The law says a governor has to call a special election if a vacancy opens up “before the 2nd Tuesday in May in the year in which a regular election is held.” The current vacancies technically opened up on the last weekday of 2017, and both seats were both up for regular re-election in 2018, so Walker claims the statute gives him an out.

Vacancies can have policy consequences.

State legislatures craft a great deal of law that has real impact on people’s day-to-day lives and exerts influence on national politics. The two vacancies in 2018 likely won’t sway what the Wisconsin Legislature does — Republicans have comfortable majorities in both chambers, and though GOP legislative leaders have had public quarrels with each other and with Walker, they are more or less in lock-step on most policy issues. But empty seats can have a significant impact of the balance of power as the Legislature takes up issues of real impact. That’s exactly what happened in the early 1960s, as state lawmakers took up one of the most consequential things they do — redrawing state legislative and Congressional districts.

Over the course of 1961, four Democratic state senators and two Democratic assembly members vacated their offices. The implications for these departures in the Senate were profound: Republicans already had an elected majority in that chamber, but by the time the Legislature took up redistricting in the summer of 1962, these vacancies had given Republicans a 20 to 9 majority. That’s a two-thirds majority with two votes to spare, enough to allow Republicans to easily override vetoes or suspend procedural rules in the state Senate.

With the absence of nearly one-eighth its membership, a body carrying out a key function of representative government was far from representative itself: “The Senate was at less than 88 per cent of its full strength,” reads the Legislative Reference Bureau report. “Almost one-third of the Democrats elected to the 1961 Senate were no longer eligible to participate; 482,275 persons were no longer represented in the Senate.”

It’s never been perfect.

A legislature is a messy human enterprise charged with carrying out lofty ideals of representation with the consent of the governed. Vacancies are just one way in which they can fall short. No matter the timing or consequences, if an officeholder resigns or dies, their constituents will be without representation in one state legislative chamber for at least some period of time.

One way to make vacancies shorter would be to give Wisconsin’s governor the power to appoint legislators to vacancies rather than simply call special elections to fill them. Special-elections at least let voters choose who fills the vacancy, but neither approach is entirely democratic, as the 1963 report noted.

“Opponents charge that [having a governor call special elections] is really inconsistent with a republiu00adcan form of government because it denies representation,” the report stated. “In many cases a vacated seat is not filled during the remainder of the sesu00adsion in which it was vacated. Even in those cases where special elections are called, the lengthy and costly process consumes so many weeks — and even months — that effective representation is seu00adverely curtailed.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us