Where In Wisconsin Do Hardiness Zone Shifts Reflect A Changing Climate?

For centuries, gardeners have depended on tradition and long-honed folk knowledge to inform their spring planting decisions. Although many American gardeners may still prefer to sow their seeds guided by the advice of their forebears today they have another source of information.

In most locations around the United States, gardeners now have at their disposal more than a century's worth of detailed local climatological data. These records provide a wealth of information about climatic trends, and they hint at the types of plants that may, or may not, survive and thrive in a vegetable patch in Beloit or a flower bed in Bayfield.

But what gardener would choose to sift through mountains of historical weather records when they could be outside getting their fingernails dirty?

That work has already been done, though, thanks to generations of mapmakers who have used ever more sophisticated methods to distill heaps of climate data. Their creations establish a geographic system called hardiness zones which since 1960 have provided an evidence-based resource for planting decisions by defining regions with similar extreme low winter temperatures. These hardiness zones can help gardeners and farmers gauge whether a plant can reasonably be expected to survive the winter in a given location.

In Wisconsin, where winters can usher in brutal cold snaps, that guidance can be key to cultivating a successful perennial garden. But in a world with a changing climate, just how accurate are these maps, and how do their makers continue to ensure these tools are as useful as possible?

A brief history of hardiness zones

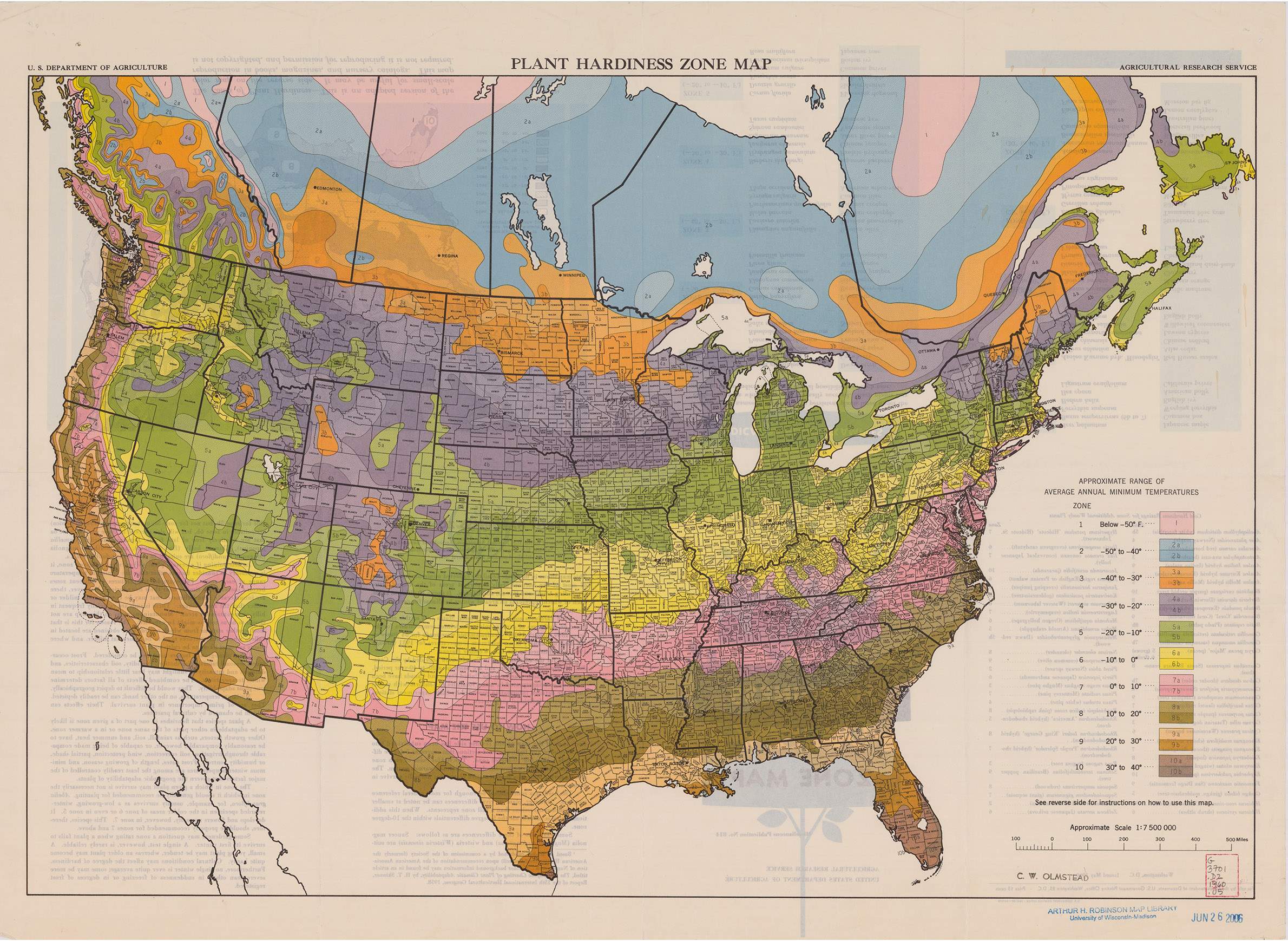

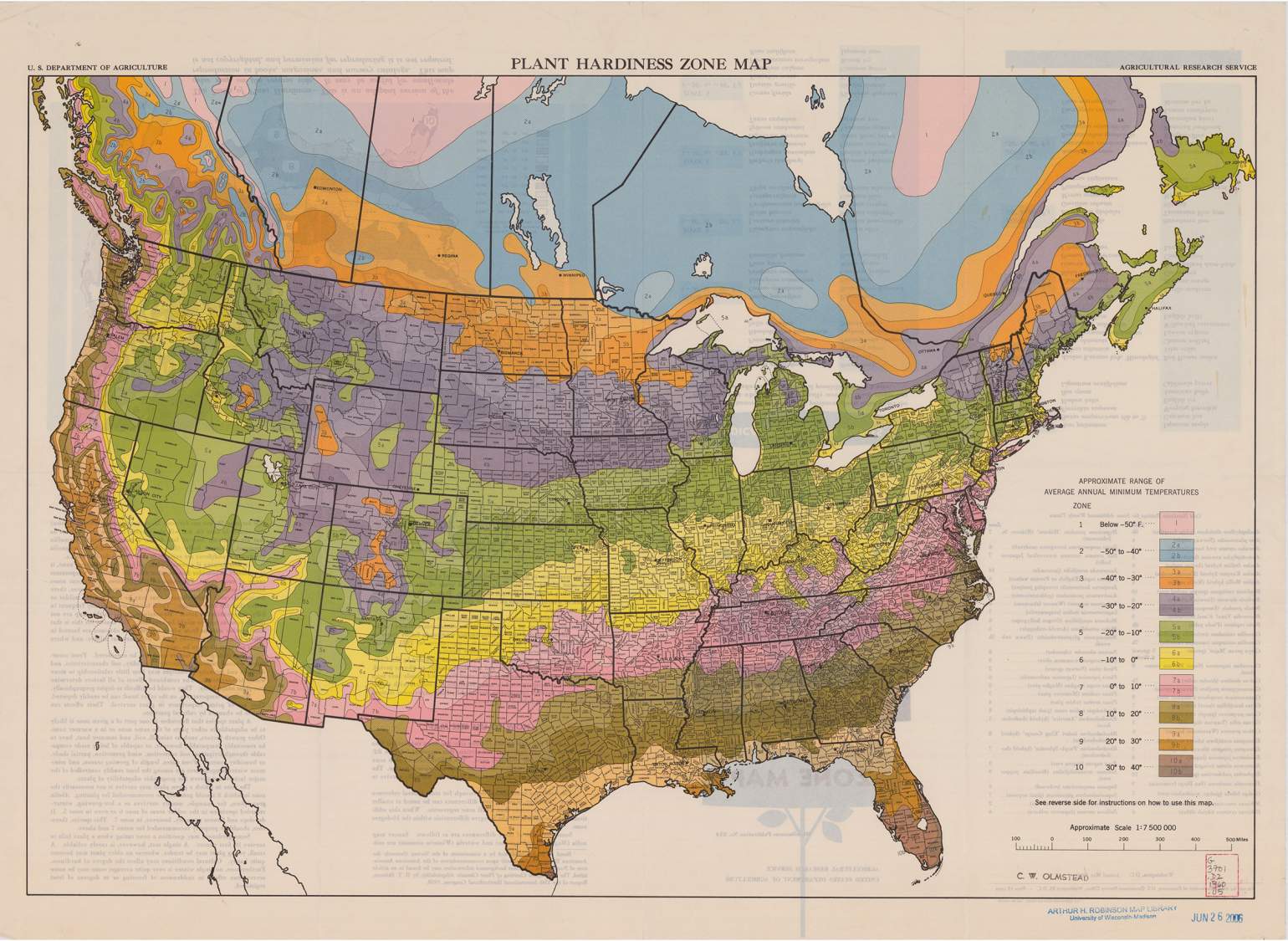

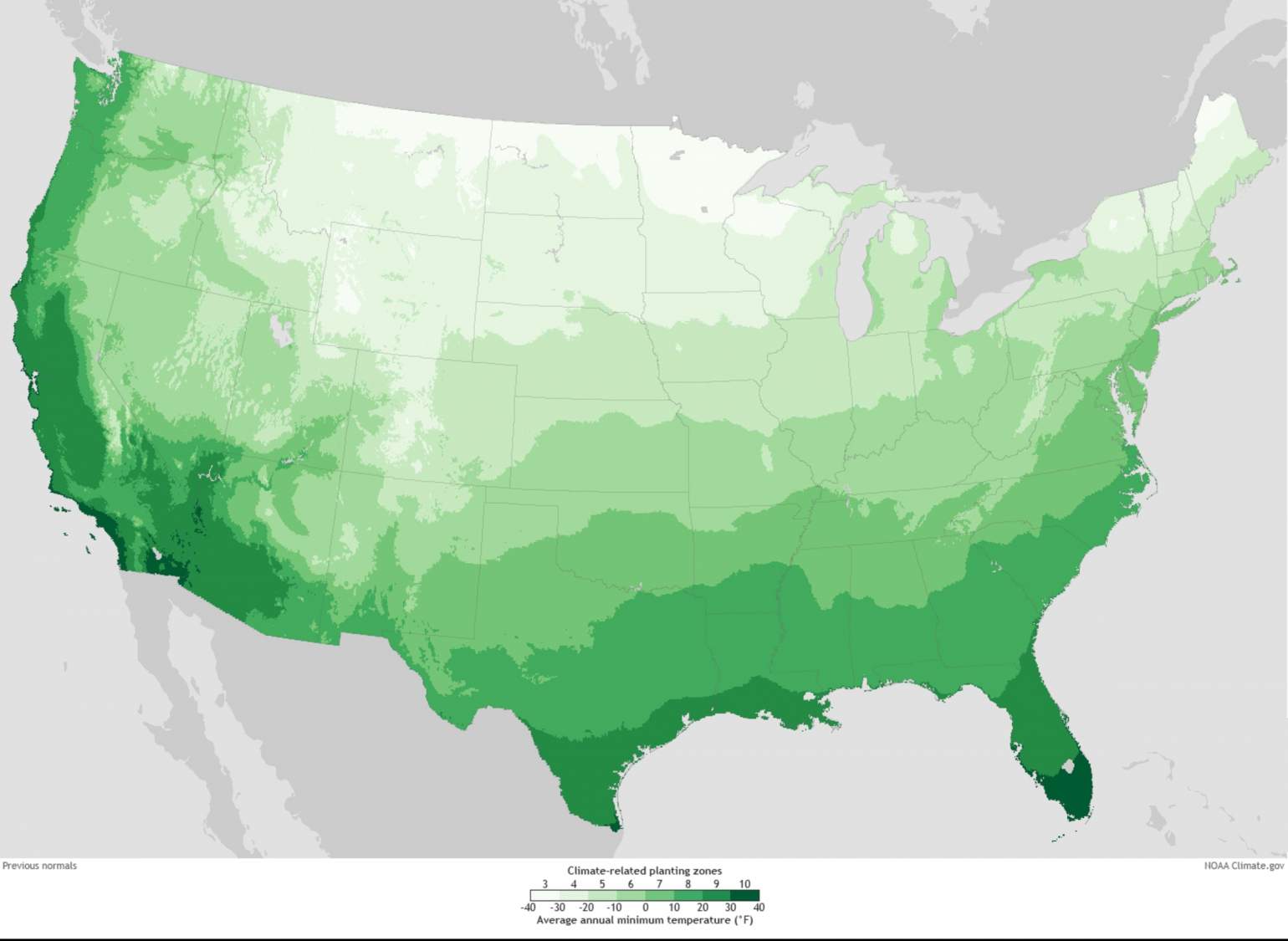

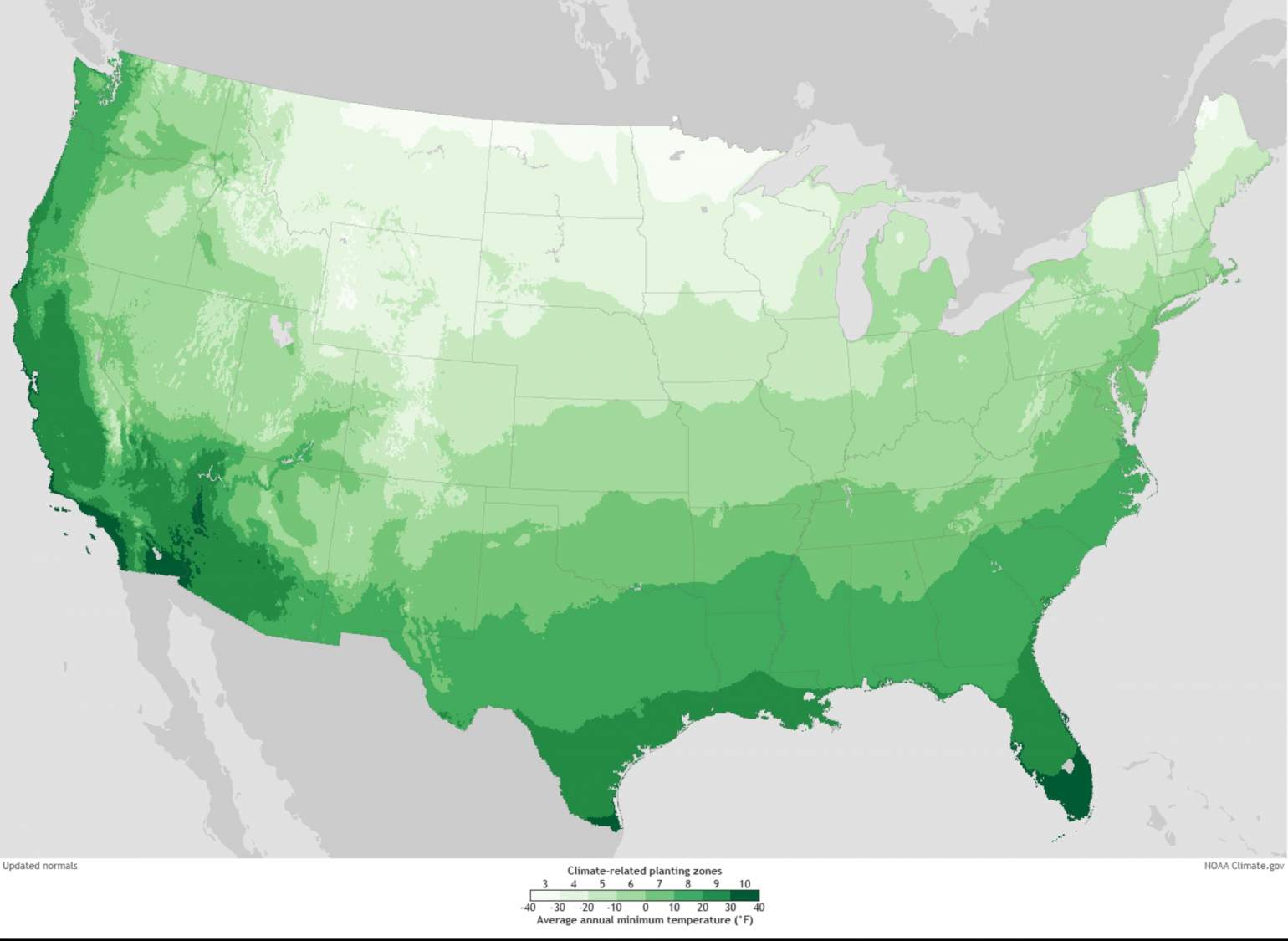

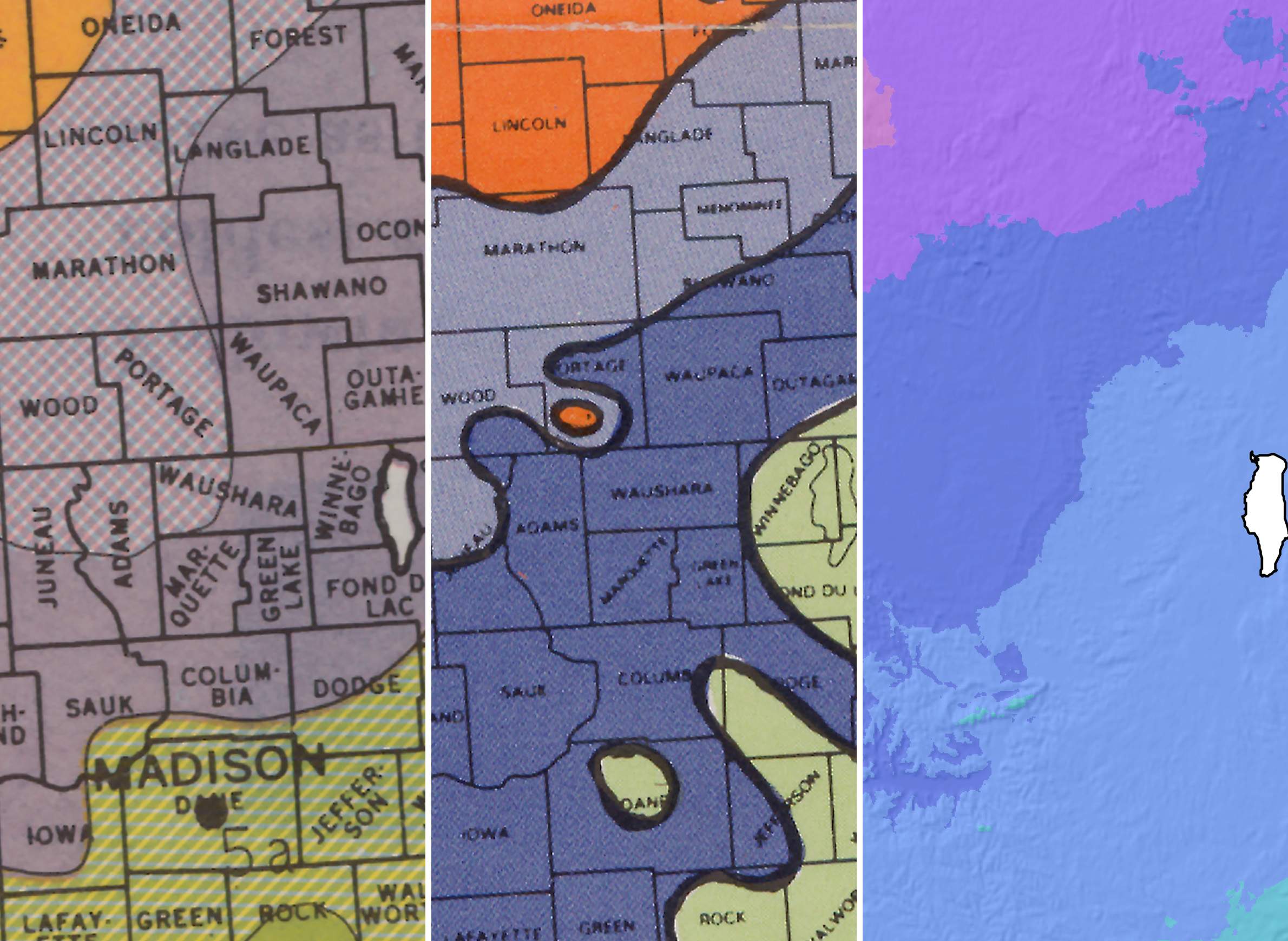

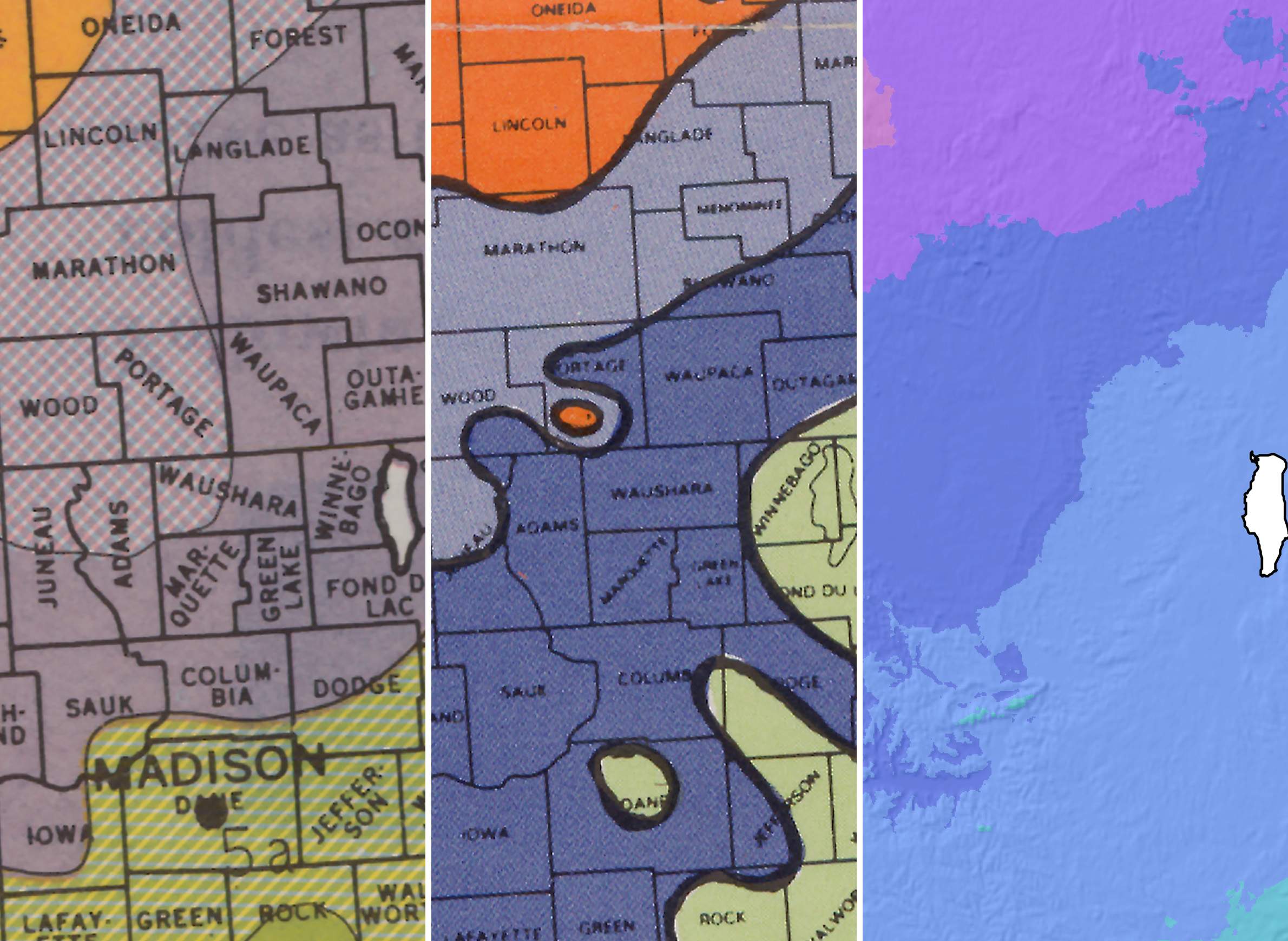

Over the past 60 years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has developed three standard hardiness zone maps, with the most recent version released in 2012. It is far more sophisticated than the previous versions released by the USDA in 1990 and 1960.

However, the 1960 map itself was a major undertaking in its own right. This work was the culmination of a long effort among horticulturists to make use of temperature data that the federal government had collected for decades via its network of weather stations dotted across the American landscape. The map split the continental U.S. into zones according to a multi-year average of extreme cold temperatures recorded at local weather stations, falling within 10-degree increments. Each of the 10 zones were subsequently divided into half-zones in an attempt to provide more detailed guidance.

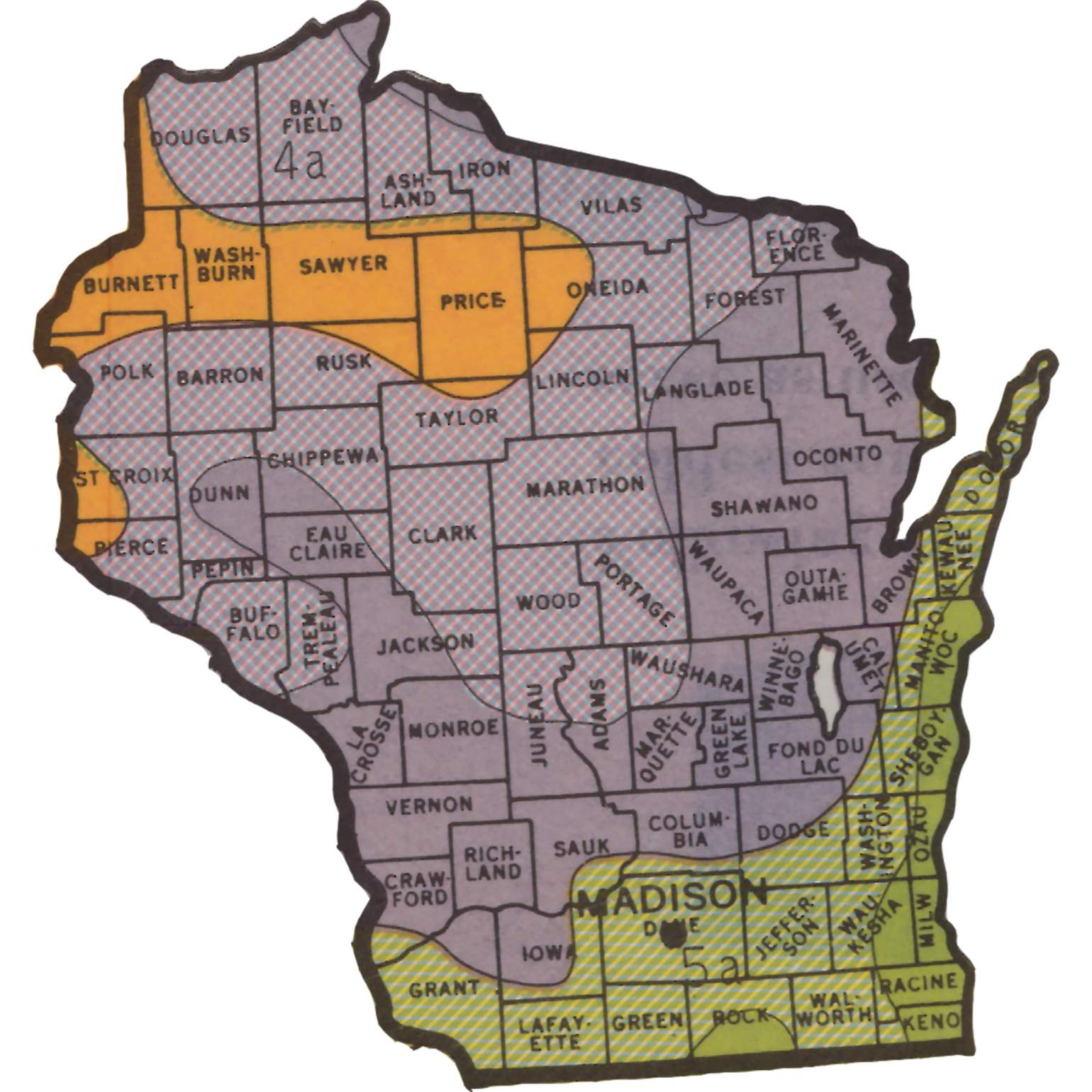

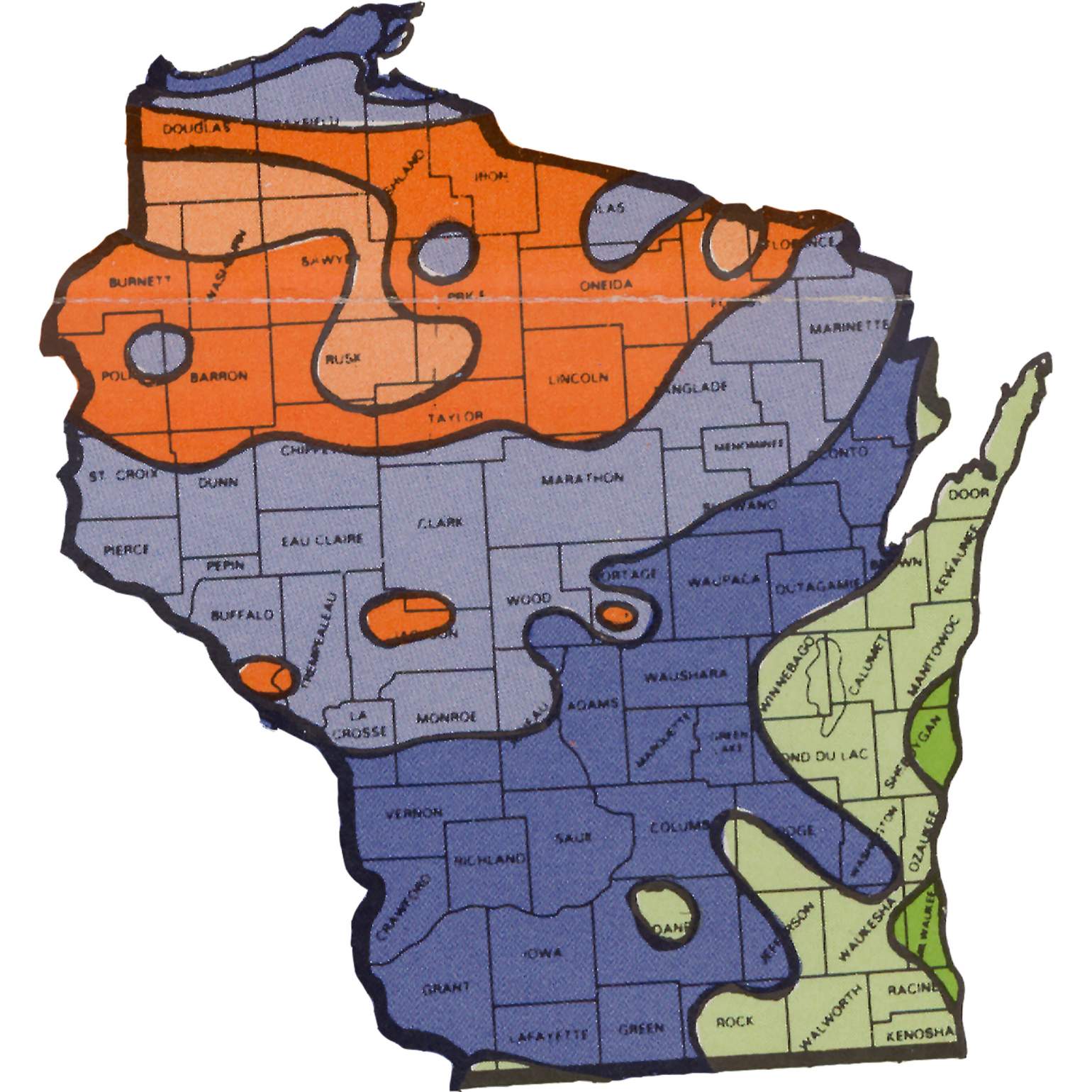

Swaths of Wisconsin fell into three zones in the 1960 map, with extreme winter temperatures ranging from -40°F in northwestern portions of the state to -10°F in the south and along Lake Michigan.

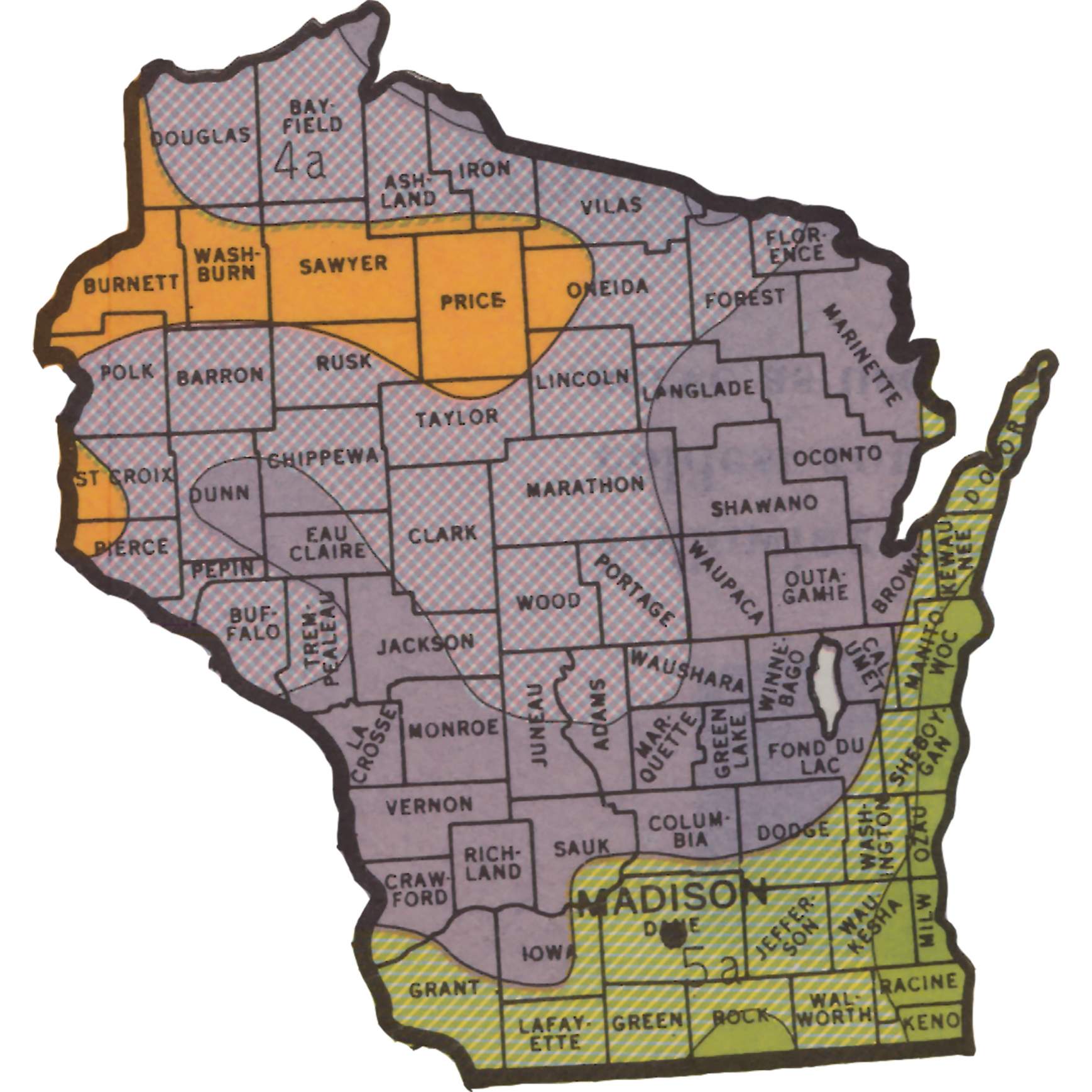

In 1990, the USDA released an updated map based on more recent climate data and defined by five-degree half-zones. That map broadly resembled the 1960 version, with some notable variations.

For instance, the coldest zone in Wisconsin, Zone 3, expanded over much of the northern third of the state, while Zone 5, Wisconsin's warmest, shrank considerably. According to this 1990 map, much of the state was actually more likely to experience colder winter extremes than the previous map had forecast.

However, the methods used by the USDA for the first two maps limited their usefulness. While each provided gardeners and farmers with an evidence-based resource using mapping techniques available at the time, they are blunt instruments by 21st century standards.

For starters, the maps were hand-drawn, and the boundaries between zones lacked spatial detail. Areas with fewer weather stations, such as the mountainous western U.S., and where records were incomplete, were particularly difficult to map in much detail. The 1990 map also drew from a relatively short time frame — just 14 years — and that period happened to include several years with colder than average winters.

These limitations — along with pressure from competing hardiness zone maps put out in the 2000s by organizations like the American Horticultural Society — led the USDA to seek an improved methodology for its mapmaking.

New technologies lead to better maps

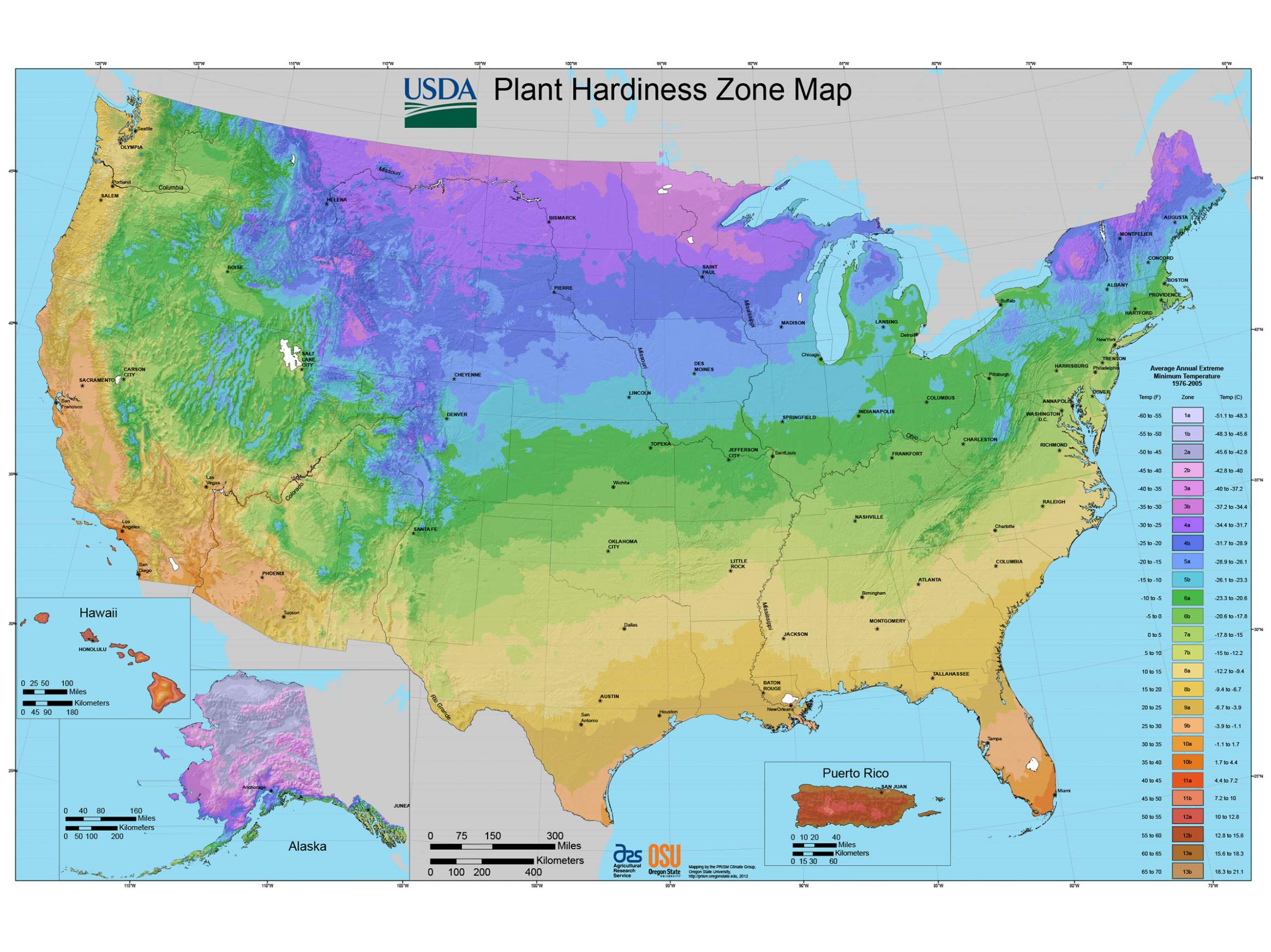

The USDA's solution to improving its hardiness zone mapping approaches came by way of the PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University headed by geospatial climatologist Christopher Daly. In the early 1990s, Daly developed computer modeling techniques that incorporated more than just weather data to map climate trends in precise spatial detail.

Crucially, Daly recognized the important role of physical geography — known as physiography in scientific circles — in constraining localized climate conditions. His models therefore incorporated variables like latitude, elevation, prevailing winds and proximity to bodies of water, all of which influence weather, including extreme winter temperatures.

The modeling tool Daly developed came to be known as PRISM, and in 2007 the USDA asked him to develop a new hardiness zone map based on its techniques.

Those techniques incorporate sophisticated quality controls, according to Daly.

"We use a number of different screening steps," he said. "The first one is that we’re pretty big sticklers for data completeness."

Generally, if a weather station is missing records for more than two days in a month, none of its data are incorporated into the PRISM model, Daly said, though that standard was relaxed slightly for the hardiness zone mapping work.

Additionally, using the physiographic parameters Daly developed, PRISM is able to forecast what a given location's temperatures would likely be.

"That gives PRISM the power to forecast even in areas where there aren't weather stations," Daly said.

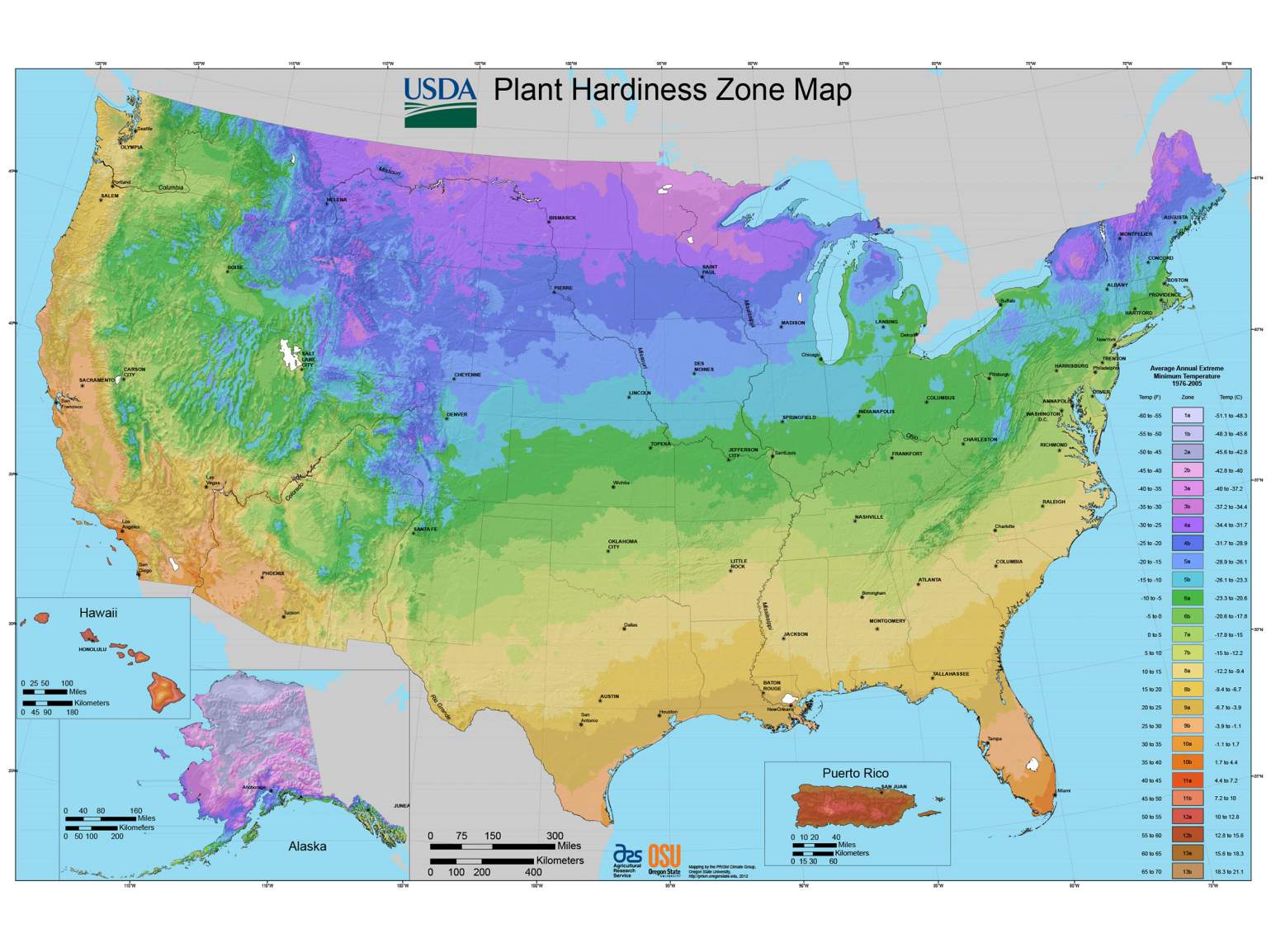

With strict quality control measures in place, and using a 30-year climate record, the PRISM group began developing a hardiness zone map with much finer spatial detail than the 1960 or 1990 iterations. The new map was complete by 2009, Daly said, though it took another 3 years for the USDA to release it because the agency needed to build digital infrastructure capable of distributing it and handling expected levels web traffic. The 2012 map was the first to not only incorporate complex computer modeling, but also to live online.

The delay turned out to be prudent as there were tens of millions of accesses within the first few weeks after it launched.

Not only was the new map more precise than ever, but it more closely resembled the 1960 version than the one released in 1990. In Wisconsin, Zone 3 reverted back to a relatively small portion of the northwestern portion of the state, centered around Hayward, while Zone 5 expanded well beyond the Lake Michigan shore to include most of southern and eastern Wisconsin.

Reflecting PRISM's incorporation of variables outside of weather data, the 2012 map also for the first time displayed the impact of physical geography on plant hardiness in Wisconsin. In particular, the boundary between zones 4 and 5 closely follows the rolling topography in parts of the Driftless area in southwestern Wisconsin. Hilltops and higher ground are part of the warmer Zone 5, while river valleys are generally classified as Zone 4.

"Cold air pools in valley bottoms and river valleys, even shallow ones," Daly said. "There is some of that in Wisconsin. Cold pools at night, especially during an arctic outbreak, and if the wind dies down, cold, dense air settles into river valleys and depressions. This can change your ability to grow certain perennials quite dramatically."

However, there are still questions about the localized usefulness of this most recent map. Lisa Johnson, a horticulture educator with University of Wisconsin-Extension Dane County, said topography remains a confounding variable for some Wisconsin gardeners, as do differences between rural and urban areas, the latter of which often experience a heat island effect.

"I take it with a grain of salt," Johnson said of the USDA's 2012 map, especially since extreme winter temperatures are not the only important parameters for gardeners and farmers to consider.

The timing of spring and autumn frosts can also dramatically impact the ability to grow certain plants, though frosts are usually more of a concern for annual flowers and crops that require a certain period of frost-free weather to reach maturity. Hardiness zones and first and last frost dates may generally follow similar trends — i.e., more northerly locales will generally have shorter growing periods and colder winter extremes — but they aren't totally correlated, Daly explained.

"One of the misuses of the map is that people don't really understand what the plant hardiness statistic is," he said. "It's often used to describe when last frost in the spring might be, but it doesn't have to do with that. You could have a plant hardiness zone that's pretty warm but the last freeze is late."

How does climate change fit in?

One major phenomenon that will likely alter Wisconsinites' ability to grow certain perennials in the decades to come is climate change. Models show that by the 2080s, many locations in Wisconsin are projected to have climates similar to those currently experienced in locales far to the south and east, like Kansas City and Philadelphia.

But while some regions in the USDA's 2012 map shifted to warmer hardiness zones from previous iterations, Daly cautioned against consulting it as a proxy for understanding climate change. That's because hardiness zone maps provide only a tiny (albeit important) snapshot into local conditions: extreme low temperatures.

Plant hardiness is "a really volatile statistic in time," Daly explained. "It's only one day per year over 30 years. Even if the average is slowly creeping up on us, as a single, volatile statistic it's just not a very good metric for looking at climate change."

His view reflects the USDA's own guidance against interpreting the maps as evidence for climate change.

Moreover, the three USDA maps were produced using different methodologies, so a comparison of their zone boundaries is as much or more a comparison of the mapmaking process as it is the underlying data, Daly said.

Another federal agency weighs in

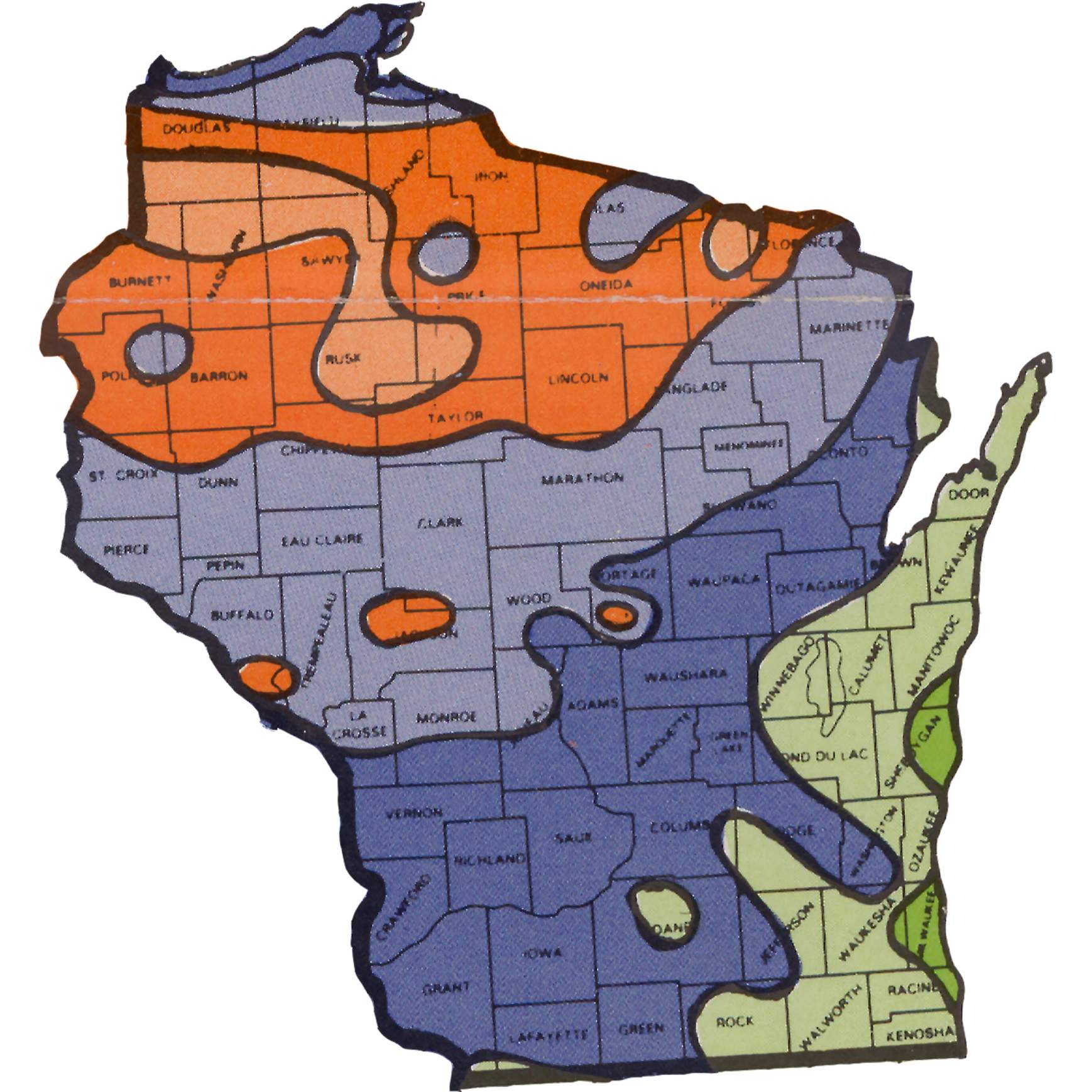

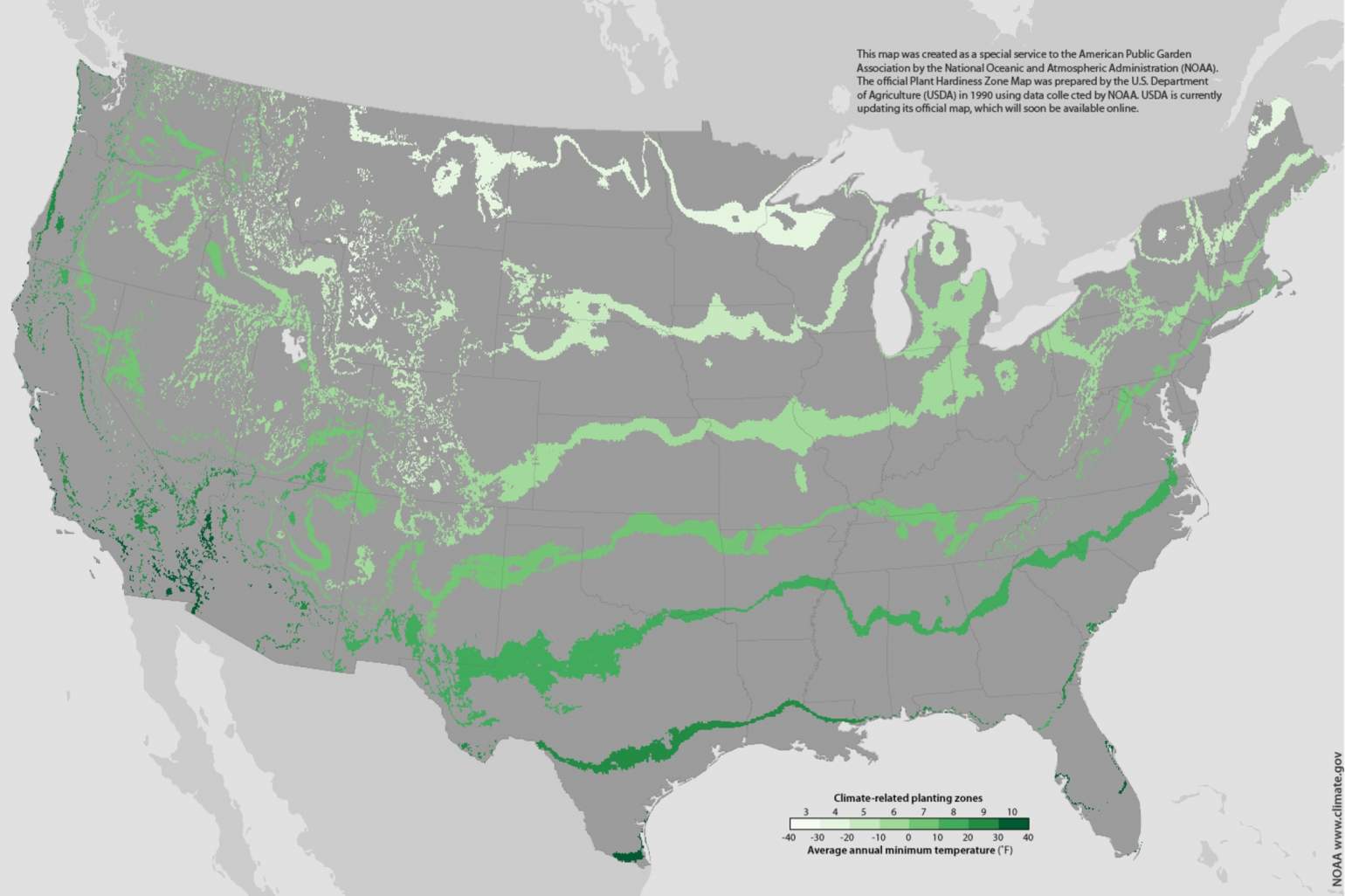

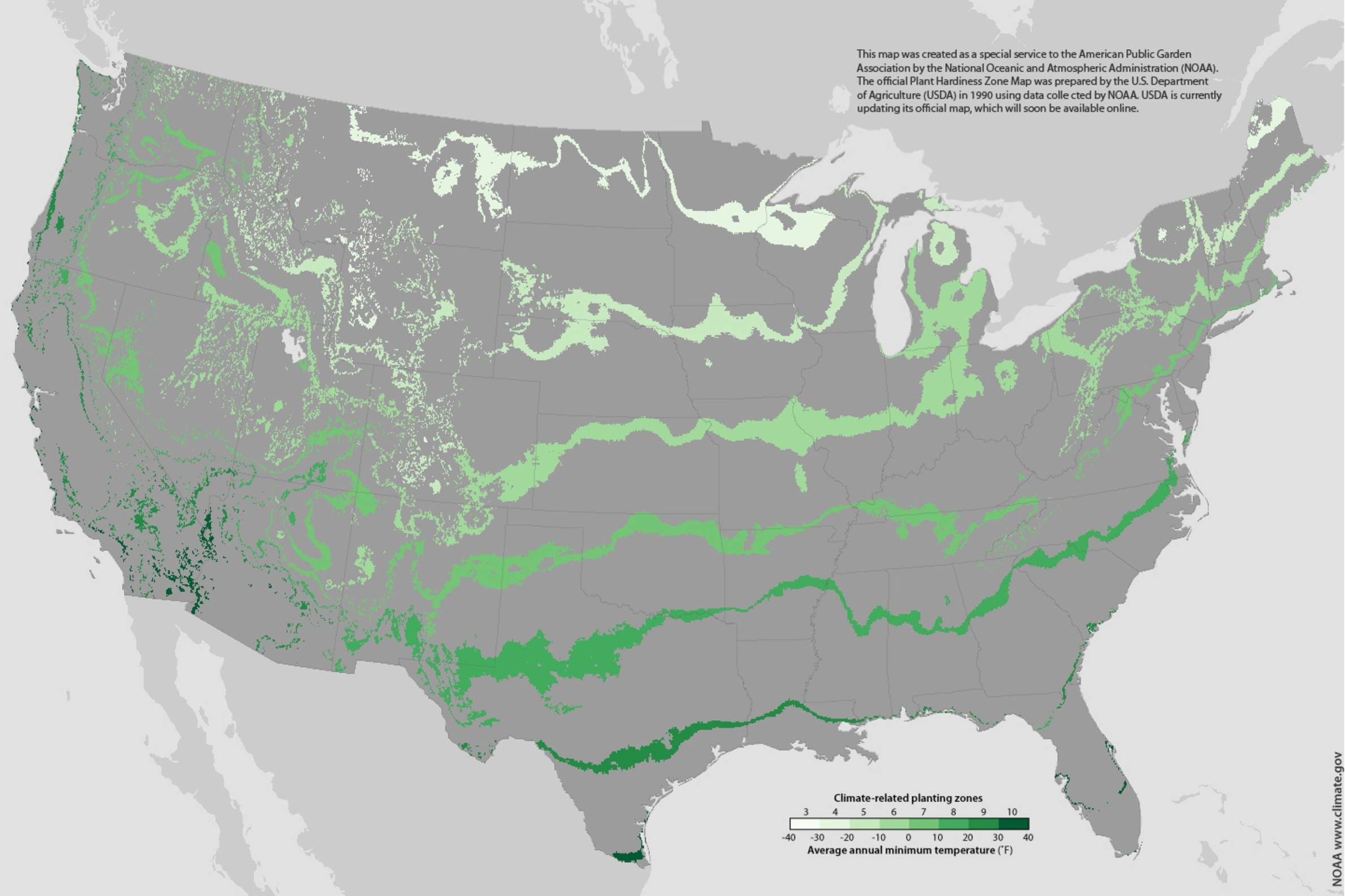

Around the time the USDA was releasing its 2012 map, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration developed another set of hardiness zone maps for the explicit purpose of tracking a changing climate.

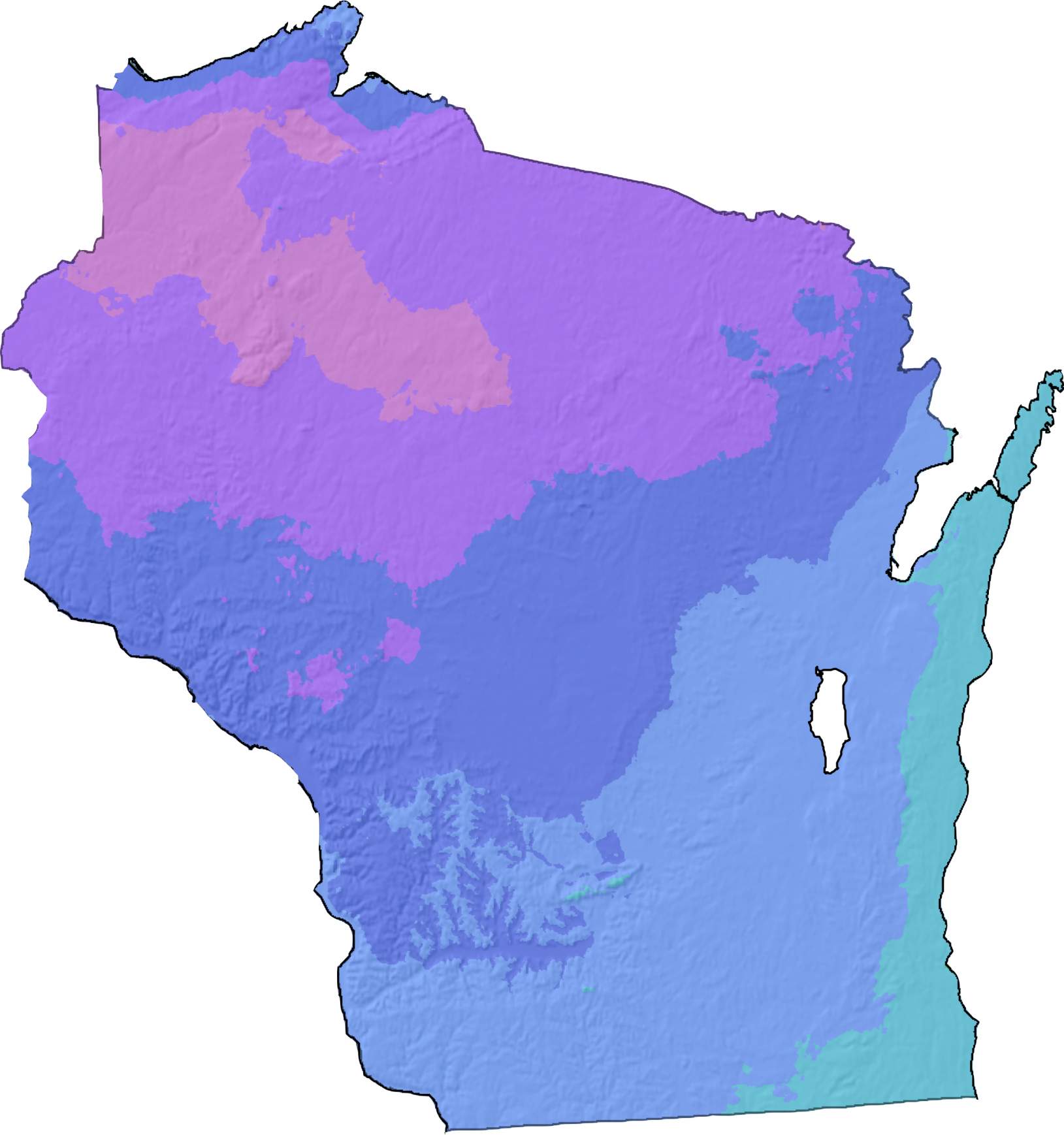

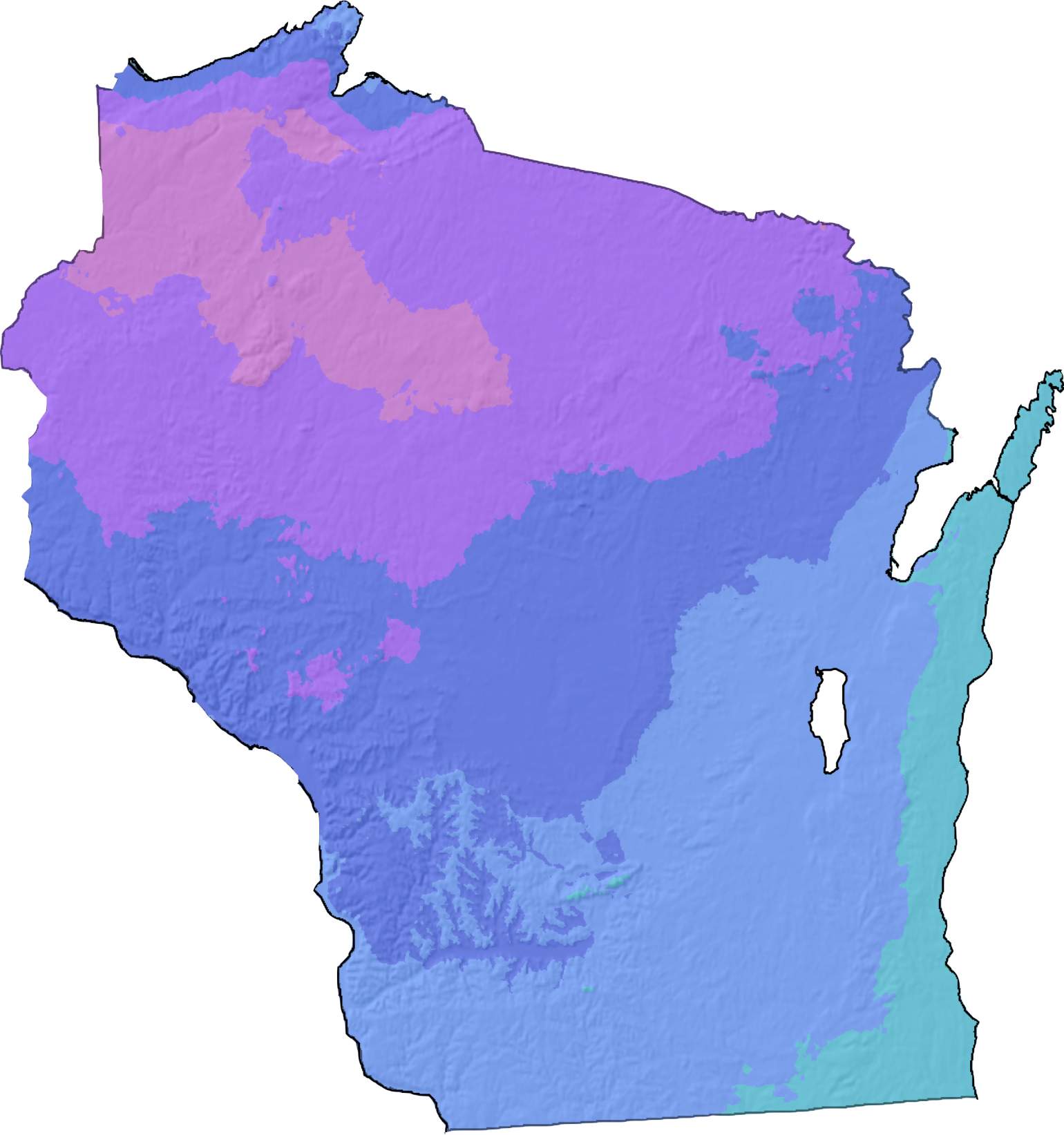

NOAA's maps are based on two 30-year periods called climate normals. One covers the period between 1971 and 2000 and the other spans 1981 to 2010. The 2012 USDA map also uses the 1981 to 2010 data, and a comparison of the two shows fairly similar zones, though the PRISM-produced map is more finely detailed and shows cold hardiness zones stretching farther south in the upper Midwest, including Wisconsin, than does NOAA's map of the same period.

At the same time, a comparison of the two NOAA maps reveals that hardiness zone shifts seen in Wisconsin could be due to the changing climate. These shifts affect a narrow band from the state's southwest corner to the Michigan border near Marinette, as well as a large region in the northern third of the state. Hardiness shifts would be expected under climate change modeling, which project a larger warming effect on nighttime minimum temperatures than on daytime highs, and hardiness zones are based on the most extreme of those minimums.

If climate projections bear out over the coming decades, hardiness zones could continue their northward march.

Oregon State researcher Christopher Daly said he is hopeful the USDA will continue to update its maps going forward, adding that he would be happy to provide PRISM's services again. He has had informal talks with the agency about an update once the latest climate normals are in after 2020.

"I would like to see the map updated every 5 years or so," he said.

Over the long-term, Daly hopes the USDA's maps could provide an increasingly detailed snapshot into local growing conditions and how they are changing due to both natural variations and human-caused climate change. Daly viewed it as a responsibility of agency to continue the updates, noting that these maps will always be in high demand by gardeners, farmers and the horticulture industry.

"Once you start leaving a map not created there's a vacuum and it'll be filled by less reliable maps. We want these to have the highest integrity possible," he said.