Why The Invasive Longhorned Tick Has Potential To Reach Wisconsin

An invasive tick species is swiftly making its way across the United States, the first to do so in about 50 years, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report issued in September 2018.

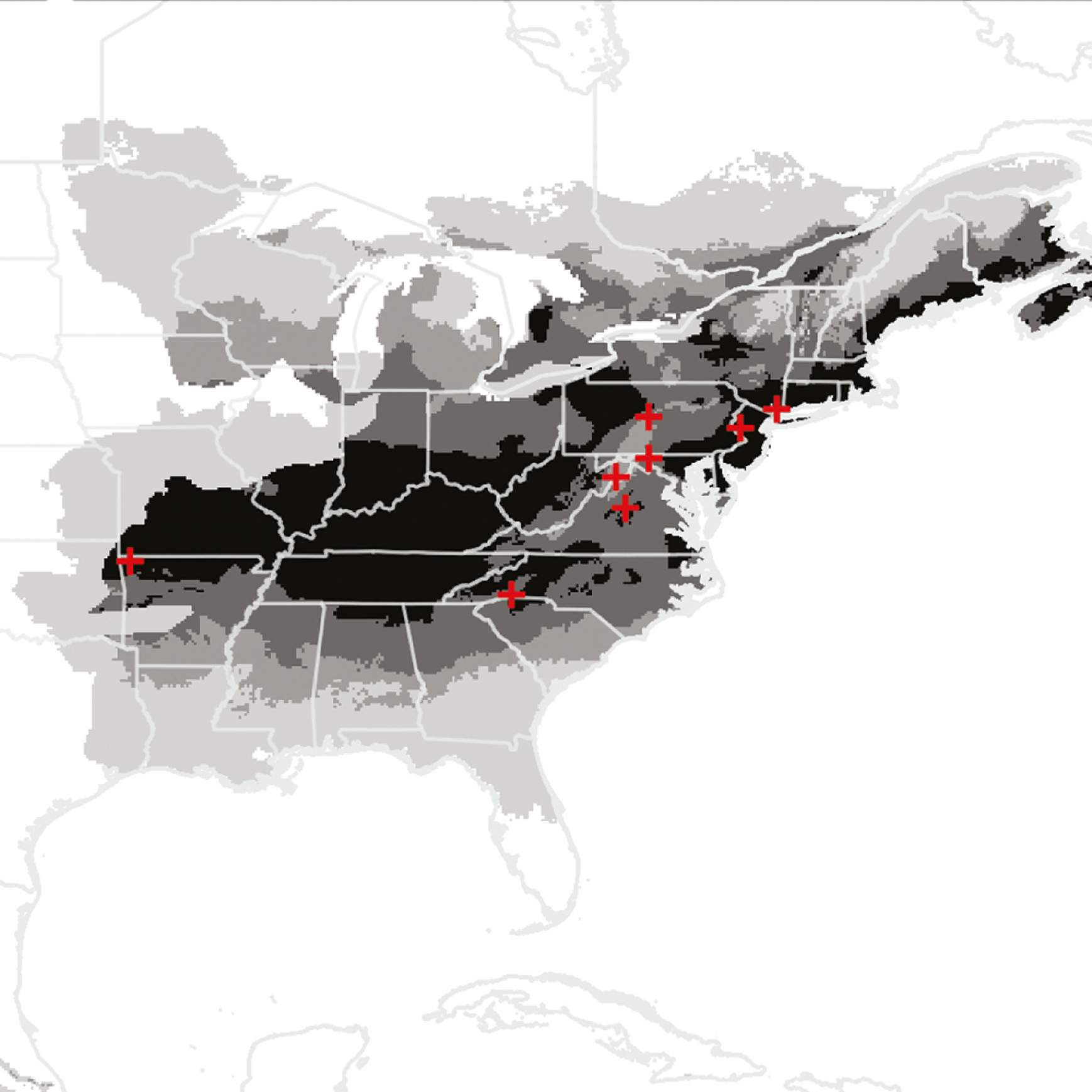

The longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) was identified in New Jersey in 2017 and has since been found in several other states, mostly along the East Coast: Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. The species has also been identified in West Virginia and Arkansas, and it is expected to spread.

There's no question in entomologist Phil Pellitteri's mind that it will be able to reach, and likely thrive, in Wisconsin.

"I've seen the distribution maps ... and it will be able to survive quite well in Wisconsin," Pellitteri said in a Dec. 19, 2018 interview on Wisconsin Public Radio's The Larry Meiller Show. "Now, how long it takes to get here is another interesting question."

A December 2018 report in the Journal of Medical Entomology identified the Midwest and southern U.S. as a "highly suitable" region for the tick.

"Large swaths of eastern U.S. interior were also classified as suitable, from northern Louisiana to Wisconsin and into southern Ontario and Quebec," the report says.

While the species — also known as Asian longhorned ticks, bush ticks and cattle ticks — is capable of carrying diseases in its native East Asia, those specimens identified in the U.S have yet to be found with any pathogens capable of infecting humans.

In Asia, the tick can transmit a slew of human diseases. One of the pathogens it transmits is severe fever and thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, which can kill upwards of 15 percent of those it infects, and in some instances up to 30 percent. It also can transmit Borrelia bacteria, some species of which can carry Lyme disease.

"My gut feeling is Lyme disease and some of those organisms are not going to be an issue because they are so tied in with ticks in the Ixodes genus and this is a different group of ticks," Pellitteri said, referencing deer ticks and related species. "But ... it's just one more thing to worry about."

Currently, the longhorned tick's threat to livestock is cause for more concern, and not only from disease. In other parts of the world, including Australia and New Zealand, the tick has been blamed for a 25 percent reduction in dairy cattle productivity because of blood loss, when one cow can play host to hundreds or even thousands of the tiny creatures at a time.

Researchers estimated that sheep in New Jersey, where the species was first discovered in the U.S., also carried thousands of the ticks by the time they were found.

No one knows exactly how the tick made it to the eastern U.S., but experts estimate that it had been on the move for a number of years before it was identified in New Jersey, likely because it was mistaken for the native rabbit tick (Haemaphysalis leporispalustris), Pellitteri said.

"I think that's why they missed it, because if you just saw it crawling around, you'd say, 'Oh that's just a rabbit tick, let's not worry,'" he said. "What got their attention is it started showing up on a bunch of things other than rabbits, including people."

The longhorned tick also has an unusual ability that appears to be a key factor in its rapid expansion: its reproduction method. A single female tick is able to produce 1-2,000 offspring without mating, according to the CDC.

"It's capable of reproducing without breeding — parthenogenetic reproduction — which you know is a game that we saw with a number of our exotic ants that have moved in," Pellitteri said.

The CDC offers recommendations for protecting people, pets and livestock from longhorned ticks, including using insect repellants and wearing permethrin-treated clothing.

One thing that's clear is there are still many unknowns surrounding the longhorned tick.

"With this added quirk of being able to breed without normal reproduction, I think gives it the potential of being a real stinker," he said.