Why Wisconsin Presents A 'Perfect Opportunity' For A Measles Outbreak

The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, thanks to a sustained public health effort built around near universal use of a safe and effective vaccine. But less than two decades later, measles is back, and at a level not seen for a quarter-century, meaning a generation of healthcare workers have little experience with the disease.

Measles is re-emerging as a public health threat thanks in part to a worldwide surge in the disease, as well as sustained concerns that vaccines are unsafe or unnecessary. These fears, including those rooted in falsified and debunked research, have propelled a rise in vaccine refusal both in Wisconsin and across the United States.

Though Wisconsin has the fifth highest rate of measles vaccine refusal in the nation, the state has not recorded a case of the disease since 2014. The U.S. is experiencing a major outbreak in 2019, however. As of early May 2019, measles cases around the nation topped 750, more than in any year since 1994. The outbreak includes cases in many Midwestern states, including Illinois, Iowa and Michigan.

As the disease spreads, one of Wisconsin's top infectious disease experts says there is a "perfect opportunity for an outbreak" in the state.

"It's actually remarkable to me that we haven't had a case yet," said Dr. James Conway, professor and associate director for health sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health. Conway discussed the risks the state faces in a May 3, 2019 interview on Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now.

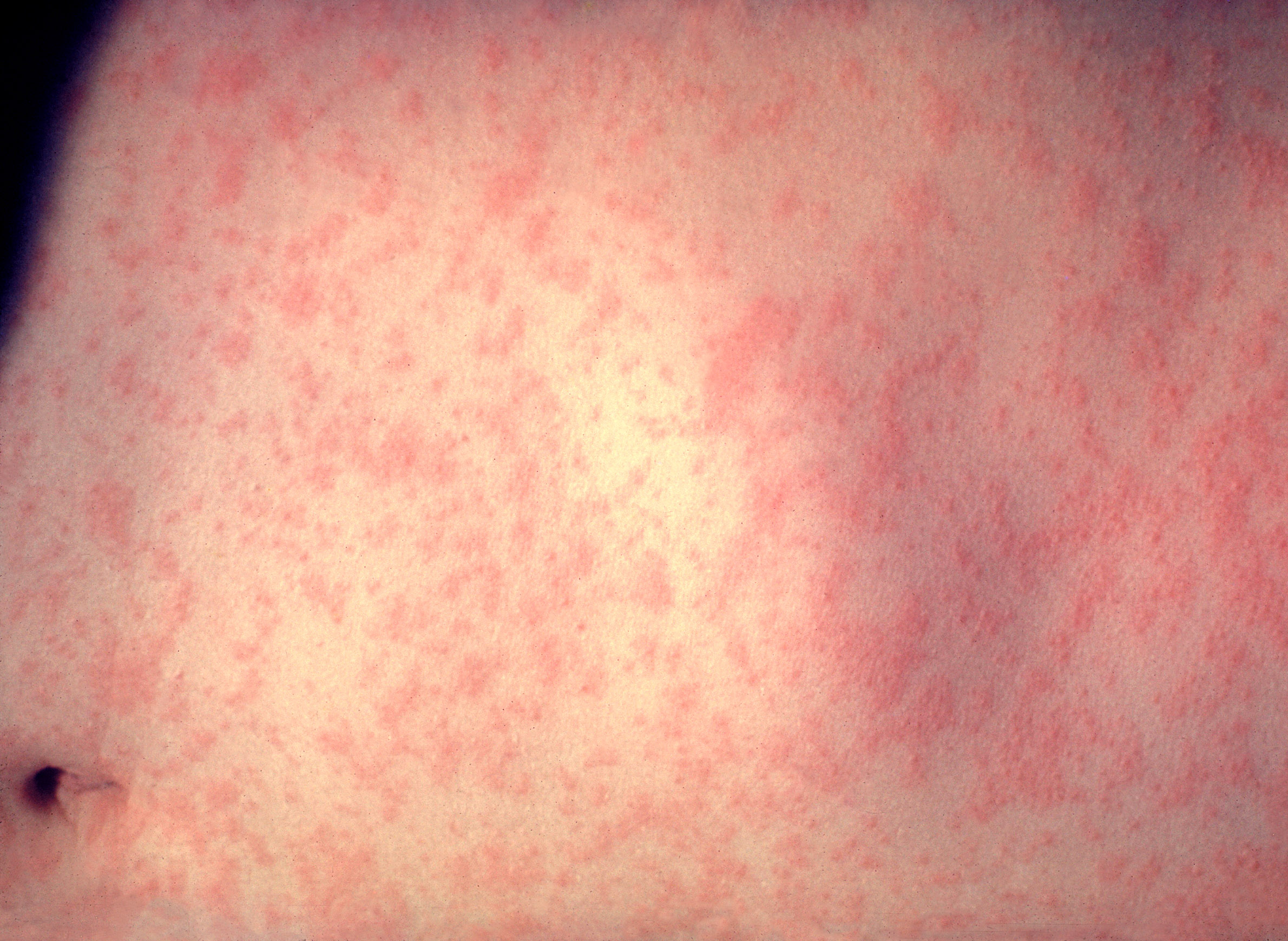

Measles is highly contagious and initially causes symptoms that can be easily mistaken for influenza or other common viruses. These ambiguous symptoms usually precede a classic measles skin rash. The disease also has a long incubation period, and people who are infected may become contagious before they notice symptoms.

These factors make measles a difficult disease to control, and they're compounded in 2019 by the growing ranks of unvaccinated individuals, particularly children, and a health system that has become unaccustomed to the disease, Conway explained.

"We've become a victim of our own success in a lot of ways," Conway told Here & Now.

In a follow-up interview with WisContext, Conway discussed fielding dozens of measles-related inquiries from doctors and nurses around the state as the national outbreak has spread. Most of them have never diagnosed measles in a patient and are scrambling to prepare for a possible cases in Wisconsin.

The advice Conway is dispensing is two-pronged. First, he said, doctors should double check that they and their patients are properly immunized. That means at least one vaccine dose for anyone ages 18 to 61, and an additional dose for healthcare workers, college students and international travelers. People 62 and older are likely to have been exposed to measles before the vaccine was developed, Conway said, meaning they are almost certainly already immune.

Children 12 months and older should also receive two doses of the vaccine. Those as young as 6 months can receive the vaccine if they're at higher risk for exposure, Conway added, such as if they're traveling internationally.

Children in Wisconsin are supposed to be immunized by the time they reach school-age, but the state's immunization law allows parents to opt out of vaccines for their children for medical, religious or "personal conviction" reasons. Amid the 2019 outbreak, Wisconsin lawmakers have proposed legislation to end the personal conviction element of the waiver.

"I really hope people reconsider not getting immunized," Conway said, adding that it is perfectly safe to receive more than the recommended two vaccine doses if someone is unsure about their vaccination history and would rather not chance it.

"It's a safe and incredibly effective vaccine," he said. "I've had it three times."

The second bit of advice Conway is giving healthcare workers is to familiarize themselves with the disease's symptoms.

"We've done such a good job of almost eliminating the disease that there's a whole generation of doctors and nurses who have never seen measles," Conway said. "It's a pretty tricky disease to diagnose even when you're dealing with it on a regular basis."

Correctly diagnosing measles often comes down to asking the right questions, Conway said, including asking whether patients were recently traveling and whether they were in contact with sick individuals.

"Instead of assuming that every fever or cough is just viral flu or something like that, [healthcare professionals] need to ask the right questions," he said.

Doctors and nurses should also be aware of the characteristics of their local communities, including local vaccination rates. About 84.8% of the state's 2-year-olds received the vaccine that protects against measles in 2018, but specific figures vary widely by county.

For instance, the rate in Clark County, just east of Eau Claire, was only about 66.4%. The county includes a large Amish community, members of which often eschew vaccination for religious reasons. A 2014 measles outbreak in an Ohio community was linked to low vaccination rates.

Health officials with the Mayo Clinic Health System in northwest Wisconsin, headquartered in Eau Claire, said they're ready for a possible outbreak.

"Preparing for potential cases is a high priority," said Dr. Janki Patel, infectious disease chair for Mayo in northwest Wisconsin. In an email, Patel detailed the Clinic's measles preparedness protocols, which include close collaboration with local health departments and Wisconsin's Division of Public Health.

"We are prepared to isolate patients who show symptoms of measles to prevent further infection, and to investigate the immune status of family members who may have been exposed," Patel said. "Also, our providers are working to inform patients of the importance of getting immunized, which is the best protection against infection."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also released a measles outbreak toolkit for healthcare providers. It largely focuses on dispelling vaccine-related fears.

Most people who contract measles recover, though complications lead to death in about two per 1,000 cases. In 2016, 90,000 people died from measles worldwide, making the disease one of the most common vaccine-preventable causes of death.