Wisconsin Packs 2 Wildly Different Winters Into 1 Season

Wisconsin's meteorological winter begins every year on Dec. 1, but bonafide winter weather didn't arrive in the 2018-2019 season until mid-January.

By Will Cushman

February 27, 2019

Ice fog over Lake Monona

Wisconsin’s meteorological winter begins every year on Dec. 1, but bonafide winter weather didn’t arrive in the 2018-2019 season until mid-January. And it arrived with surprising force, as the atmosphere suddenly unleashed a sucker punch of pent up winter energy and some of the coldest and snowiest weather Wisconsinites have experienced in decades.

“In a nutshell, I would describe it as weather whiplash,” said Steve Vavrus, who is a senior scientist for the Center for Climatic Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. “We’ve had two very distinct winters this year. It’s unusual to have such distinct seasons and to have such a very, very clear boundary between them. It’s been very strange.”

That boundary is so clear that it can be pinned to a single date in 2019, Vavrus said.

“For much of Wisconsin, in particular southern Wisconsin, you can define the beginning of winter as Jan. 18,” he said. “It was mild and there was no snow cover on the ground to that point, and then we got four inches of snow and much colder.”

Temperature data from communities around Wisconsin show this demarcation clearly, as daily highs and lows generally remained above normal until on or around Jan. 18, when they plummeted.

The snow and cold have hung on since then, breaking daily and monthly records around the state and wreaking havoc on water systems, road infrastructure, municipal budgets, school calendars, perennial crops and farm buildings. On the flip side, skiers and snowmobilers have been having a ball — when it’s been warm enough to be outdoors — to the benefit of the tourism industry, and business is booming for plow drivers and mechanics. So, what gives? What’s behind this winter’s dramatic and sudden role reversal?

Two winters, one culprit

The bifurcated winter of 2018-2019 is largely a tale of two jet streams, or rather two jet stream locations, explained UW climatologist Steve Vavrus.

The northern polar jet stream is a narrow band of fast moving westerly air that meanders high in the atmosphere around the northern mid-latitudes. The jet stream often acts as a barrier between warmer air to the south and cold Arctic air to the north. When the jet stream is north of Wisconsin, as it was during the first part of the winter, the weather is often warmer than usual. And when the jet stream flows south, it brings the polar chill with it.

That’s precisely what happened in the middle of January.

“The jet stream dipped way south in January and has stayed south,” Vavrus said. The accompanying sudden and extreme shift in temperature caught many in the state by surprise.

That’s the nature of the jet stream, Vavrus said, comparing its unpredictable circulation through the upper atmosphere to the chaotic movement of fast-flowing water.

“Why the jet stream does what it does over a given day, week or month, a lot of it is just random processes or things we haven’t been able to understand,” Vavrus said.

Even the factors that are known to play a role in the jet stream’s migration aren’t necessarily predictive of its behavior.

“For instance, we understand that El Niño tends to push the jet stream north,” said Vavrus. “But that’s just on average and there are plenty of exceptions.”

El Niño is a common term for the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, which is a periodic climatic phenomenon driven by warming in the eastern equatorial waters of the Pacific Ocean. This fluctuation can have global atmospheric effects and, when strong enough, the effects of El Niño in Wisconsin can include warmer and wetter winters. A strong El Niño last formed over the winter of 2015-16, contributing to 2016 being identified as the third-consecutive warmest year on record.

A weak El Niño formed in February 2019, after months of mixed signals. It has so far been so feeble that climate scientists doubt that it’s had an influence on Wisconsin’s winter, even the warmer-than-normal first half.

“I wouldn’t attribute what we saw here in December to El Niño,” said Dan Vimont, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and director of UW-Madison’s Nelson Institute for Climatic Research. “If it were a massive [El Niño], we might be able to say there’s something happening here.”

And even still, Vimont and Vavrus noted that the recorded variation in El Niños makes it difficult to predict the effects of even a major event on the jet stream and Wisconsin’s weather.

Of the other factors thought to affect the jet stream, Vavrus said there is one present in abundance in Wisconsin after a series of big storms: snow cover. In fact, there is plenty of snow cover across the Great Lakes region.

“There is a bit of a feedback loop … when you get cold air and snow cover, it can chill the atmosphere and play a role in stagnating the air,” said Vavrus.

It’s possible that all the snow cover in Wisconsin and neighboring states is making it more likely that the jet stream stays in place.

A broken record and breaking records

The ample snow cover across Wisconsin is largely thanks to the dynamics of the jet stream, which since mid-January 2019 has acted like a conveyor belt by bringing winter storms through the state with such persistence that many communities, including Eau Claire and Wausau, have shattered longstanding snow accumulation totals for February.

“Looking at the jet stream map for the last month or so, not only is the jet stream south of Wisconsin, but it’s also exceptionally strong,” said Vavrus. “It’s like a jet stream highway for storms from the west into the Great Lakes. It really is the optimal track for winter storms to tap into.”

The February storms that have brought the abundance of snow, ice, rain and freezing rain to various parts of Wisconsin are not necessarily atypical for this time of year, beyond the total precipitation they’ve unloaded due to their frequency and size.

“It’s an odd month in terms of typical snowfall,” said Steve Ackerman, professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at UW-Madison. “But this is a typical pattern where we see mid-latitude cyclones come through, then it clears out and gets sunny. We’ve seen patterns like this in the past, but it’s not necessarily something we’ve seen in the last five years.”

It’s been much longer since Wisconsinites last experienced the extremely low temperatures seen across the state at the end of January and beginning of February. Though somewhere in the state usually experiences temperatures as low as -30 °F each winter, the polar vortex’s southern intrusion in late January brought extreme lows to much wider swaths of the state than usual.

A weather station in the village of Butternut, in Ashland County, recorded a temperature of -49 °F on Feb. 1, 2019. That figure is only six degrees shy of the all-time lowest annual air temperature recorded in the state, which hit -55 °F over Feb. 2 and Feb. 4, 1996 in the village of Couderay in Sawyer County.

Indeed, the temperatures throughout most of Wisconsin between Jan. 30 and Feb. 1, 2019 were the lowest they had been since 1996. Many locations, including La Crosse and the community of Mather near Tomah, tied or broke daily, monthly or all-time cold records sometime in the three-day period. Madison’s low of -26 °F on Jan. 30 and Jan. 31 tied for the fifth coldest temperature ever recorded in the city and the coldest in nearly 30 years.

“Every once in awhile you get a little piece of the Arctic that makes its way all the way down to the Great Lakes states,” said Jonathan Martin, professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at UW-Madison, in a Feb. 1 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now. “It’s not unprecedented, but it is not frequent.”

The record low temperature in Madison stands at -37 °F, a record set on Jan. 30, 1951. The extreme cold snap of 2019 is reminiscent of 1951 in another way: an astoundingly rapid and pronounced thaw that followed.

According to data recorded in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency’s Applied Climate Information System, or ACIS, the temperature in Alma, a community on the Mississippi River north of La Crosse, rose 52 degrees over the course of a single day on Feb. 2, from a low of -29 °F to a high of 23 °F. Meanwhile, temperatures in many areas of Wisconsin rose by 70 to 80 degrees between the early morning hours of Feb. 1 and the afternoon of Feb. 3, with the temperature rising an astonishing 91 degrees near Mather, from -47 °F to 44 °F.

“These numbers are mind-boggling,” said Vavrus, though he explained that rapid warm-ups from extreme lows are not necessarily atypical, if usually less pronounced, pointing to a similar warm-up following 1996’s record-breaking freeze.

Other regions in North America, in particular the western plains, sometimes experience huge temperature fluctuations in a matter of minutes thanks to phenomena known as Chinook winds, though they don’t reach Wisconsin.

Two-day temperature swings aren’t tracked like precipitation and daily temperatures, so it’s difficult to state definitively whether Mather’s 91-degree temperature swing in early February was truly unprecedented. However, a two-day warm-up from Feb. 9 to Feb. 11, 1951 was the closest temperature swing WisContext identified using data from ACIS. During that event, the temperature in nearby Sparta rose 87 degrees, from -38 °F to 49 °F, and temperatures in several other communities rose some 70 to 80 degrees.

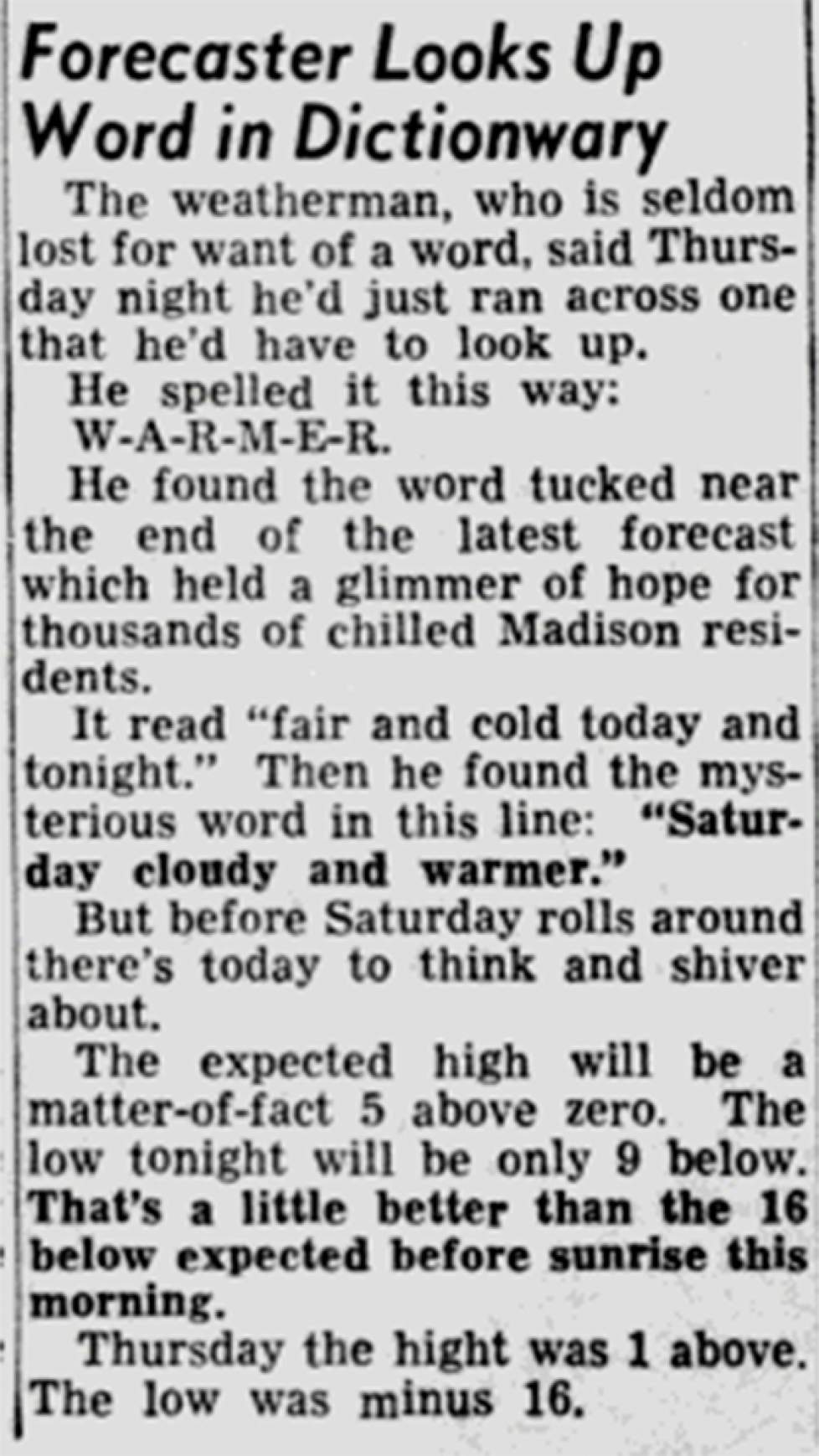

It was perhaps an even more welcome thaw for Wisconsinites then, as extremely low temperatures had been lingering for more than a week. Below headlines about troop movements in Korea, the Wisconsin State Journal‘s front page for Feb. 9, 1951 included several weather-related stories, including one with the headline “Forecaster Looks Up Word in Dictionwary [sic].”

It began: “The weatherman, who is seldom lost for want of a word, said Thursday night he’d just ran across one that he’d have to look up. He spelled it this way: W-A-R-M-E-R. He found the word tucked near the end of the latest forecast which held a glimmer of hope for thousands of chilled Madison residents.”

Extreme weather spawns uniquely Midwestern stories

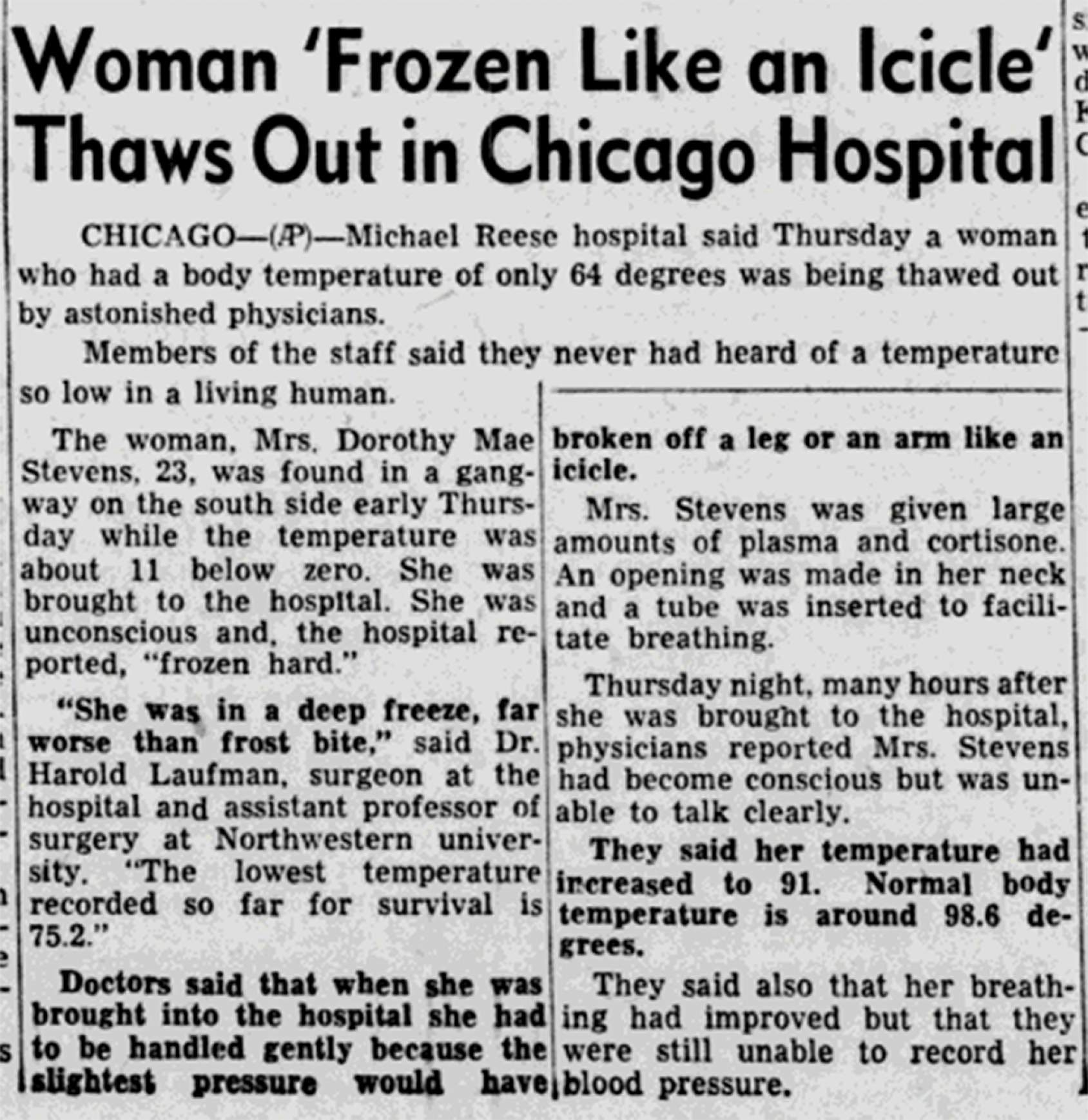

The front page of the Feb. 9, 1951 edition of the State Journal featured another article with the headline “Woman ‘Frozen Like an Icicle’ Thaws Out in Chicago Hospital.” The article detailed the harrowing story of a young woman with a body temperature of 67°F, found unconscious in subzero conditions in Chicago. Newspapers around Wisconsin followed the story, which was a particularly dramatic example of the effects of the extreme weather experienced throughout the region.

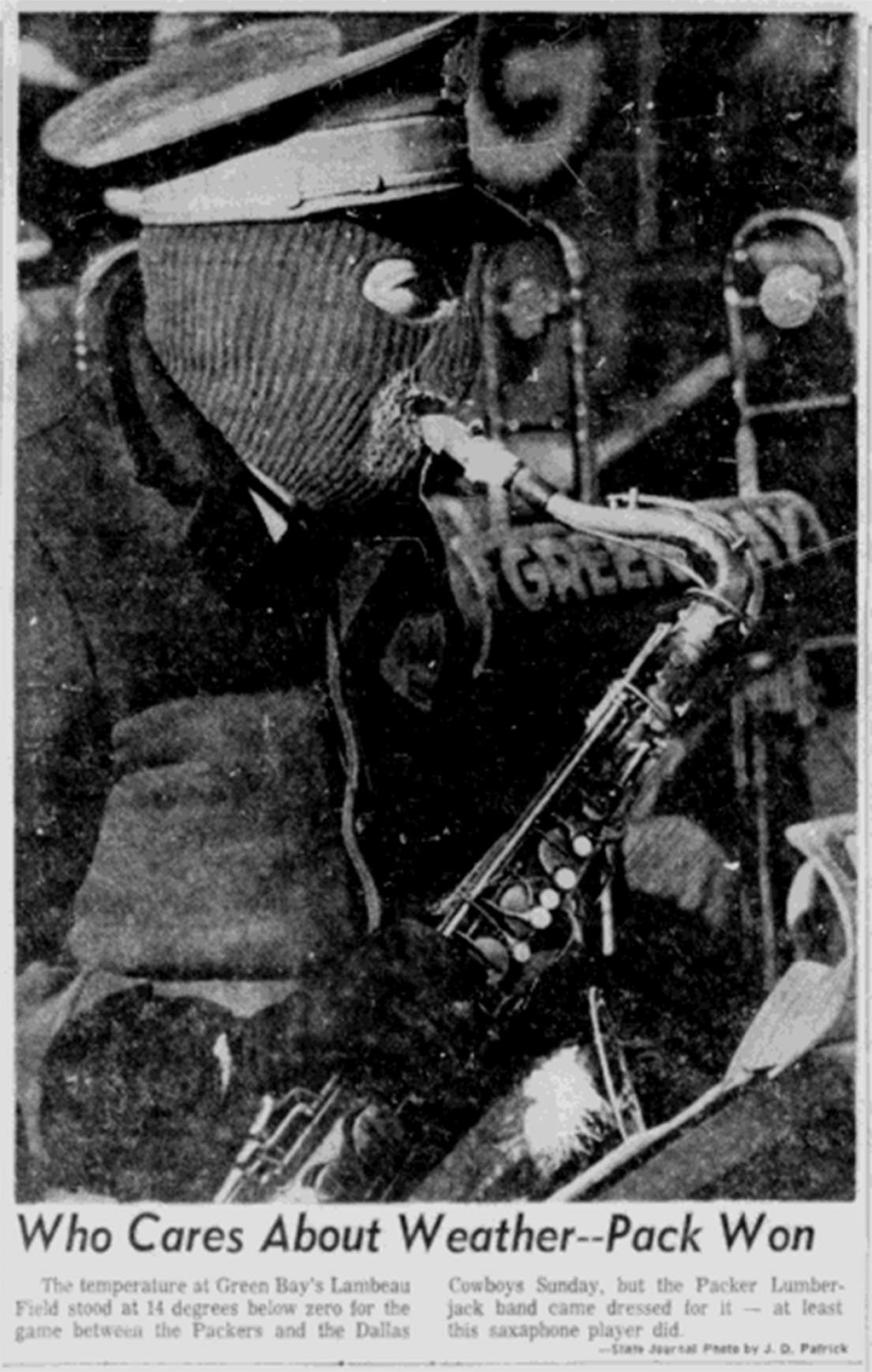

Morbid fascination with extreme winter weather and the perils it presents has long been a part of the Great Lakes region’s cultural fabric. Well-known stories range from Algonquin legends centered on the mythical man-eating wendigo, to the shockingly abrupt and severe Armistice Day blizzard of 1940, which killed nearly 150 people, to the legendary 1967 NFL Championship Game between the Green Bay Packers and the Dallas Cowboys. The game was played in bone-chilling temperatures at Lambeau Field, and became widely known as the Ice Bowl.

There are also the stories that Wisconsinites share among their friends and families, which like fishing tales can sometimes stray into hyperbole and one-upmanship, though they often needn’t.

In Wisconsin Folklore, a book published in 1999, UW-Madison professor emeritus of comparative literature and folklore studies James Leary wrote: “While legendary and tall-tale accounts associated with winter circulate widely in Wisconsin, they are not as common as true stories on recurrent themes. Over the years I have built up my own repertoire of personal stories regarding the biggest snowfall, or the coldest day, or the most treacherous driving, or the most consecutive days of shoveling I have ever experienced during a Wisconsin winter.”

Anne Pryor, a former official state folklorist for Wisconsin, told WisContext that extreme winter weather is fodder for stories and mythmaking precisely because its experience is so acute and exceptional.

“People tell stories about their experiences, and when they’re caught in or observe an extreme event or something they couldn’t explain, or had a particular family event that was affected in some way [by] extreme weather, they’re going to tell stories about that,” Pryor said. “Then stories get passed down from generation to generation.”

Pryor and climatologist Steve Ackerman, who are married, joined forces in the early 2000s to collect Wisconsinites’ weather-related stories as part of an educational project funded through UW-Madison. Titled Wisconsin Weather Stories, the project combined narrative storytelling with scientific understanding of weather phenomena.

“The goal of the project was to work with Wisconsin teachers and to help them understand how weather and weather stories could be part of the curriculum in their classroom,” Pryor said. “We collected some great stories.”

In addition to recollections of the Ice Bowl and dangerous encounters on Lake Superior, Pryor said many of the stories centered on traveling the state’s treacherous roads. It’s a topic about which many Wisconsinites can share their own harrowing tales, which now include a 131-vehicle pileup on Interstate 41 near Neenah, which killed one person and injured 71 others on Feb. 24. The pileup, caused by blizzard conditions, adds one more dubious record for the 2018-2019 winter season: it is the largest crash, as measured by vehicles, in state history.

Placing weather into the longer-term patterns of climate

As 2019 produces a fresh collection of personal stories and records for the history books, Anne Pryor and Steve Ackerman said that a changing climate is also changing the Wisconsin’s weather stories.

“We can’t treat stories of extreme weather today the same way we could in 1940 or 1960,” Pryor said. “The context of people’s stories of extreme winter is changing, and the stories being told are part of that new context.”

Climatologists labor to point out that a story about a singular weather event or season must be understood as simply that: anecdotal evidence, which is highly variable and difficult to parse from broader climatic trends.

However, one potentially relevant tidbit of data from the winter of 2018-2019 was the daily lows, which were relatively warmer compared to normal lows than daily highs were when compared to normal highs. This is consistent with patterns seen in Wisconsin’s changing climate since 1950.

Steve Vavrus said the winter of 2018-2019 is a good reminder of how the short-term variability of weather should not be confused for longer-term climate trends.

Variability between years is present in all sorts of weather data. For instance, Madison’s monthly highs and lows for January, which range from -37 °F in 1951 to 58 °F in 1888, swing wildly from year to year and occasionally within the same year. This variability is hidden when the data are averaged out to mean, or normal, values.

Indeed, Vavrus said that when everything is averaged out in the end, Wisconsin’s 2018-2019 winter temperatures will likely wind up appearing fairly typical.

“What’s going to happen is the temperature for southern Wisconsin is going to look about normal” when the entire winter is considered, Vavrus said.

The extremely cold temperatures and record-breaking snow totals in Wisconsin in the winter of 2018-19, Vavrus added, “don’t refute climate change, but are a spectacular example of how the atmosphere can behave in a very contrarian way.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us