Wisconsin's Remaining Effigy Mounds Are The Tip Of A Historical Iceberg

The ways in which contemporary Wisconsinites interpret and value the state's ancient effigy mounds continue to evolve. Since they were first found by European-American people who settled in the region and subsequently destroyed via agriculture and construction, excavated by archaeologists or preserved for posterity, interpretations of their origins and meaning has changed, as has interest in protecting them.

For instance, the protected status of mounds in the state was under attack over the course of 2016. State legislators considered easing laws that prevent mounds from being disturbed, damaged and destroyed if human remains are present, an effort that largely centered around a quarry near Madison with mounds on its property. After swift pushback from Native Americans, historians and other preservation advocates, proponents of allowing more excavation of mounds abandoned their idea.

Preservation efforts advanced that same year. In November 2016, the National Park Service designated the Man Mound near Baraboo a national historic landmark. This human-shaped mound is the only remaining effigy of its type.

In addition to their value as sacred sites for Native Americans, effigy mounds can reveal much about the people who inhabited the upper Mississippi River region over the last couple of millennia. Effigy mounds are burial sites and, just like a tombstone, have more to them than is immediately apparent.

Amy Rosebrough, an archaeologist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, explained what mounds can reveal about their builders in a May 3, 2016 presentation at the Wisconsin Historical Museum in Madison. Her talk, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place, offered an overview of effigy mounds' historical context, how they differ from similar archaeological features in the region, and how they can shed light on everything from housing to agriculture to power dynamics among ancient native societies.

Rosebrough has spoken extensively about effigy mounds on Wisconsin Public Radio, including on The Larry Meiller Show in February 2015, and on University of the Air in November 2014 and November 2011.

Key facts

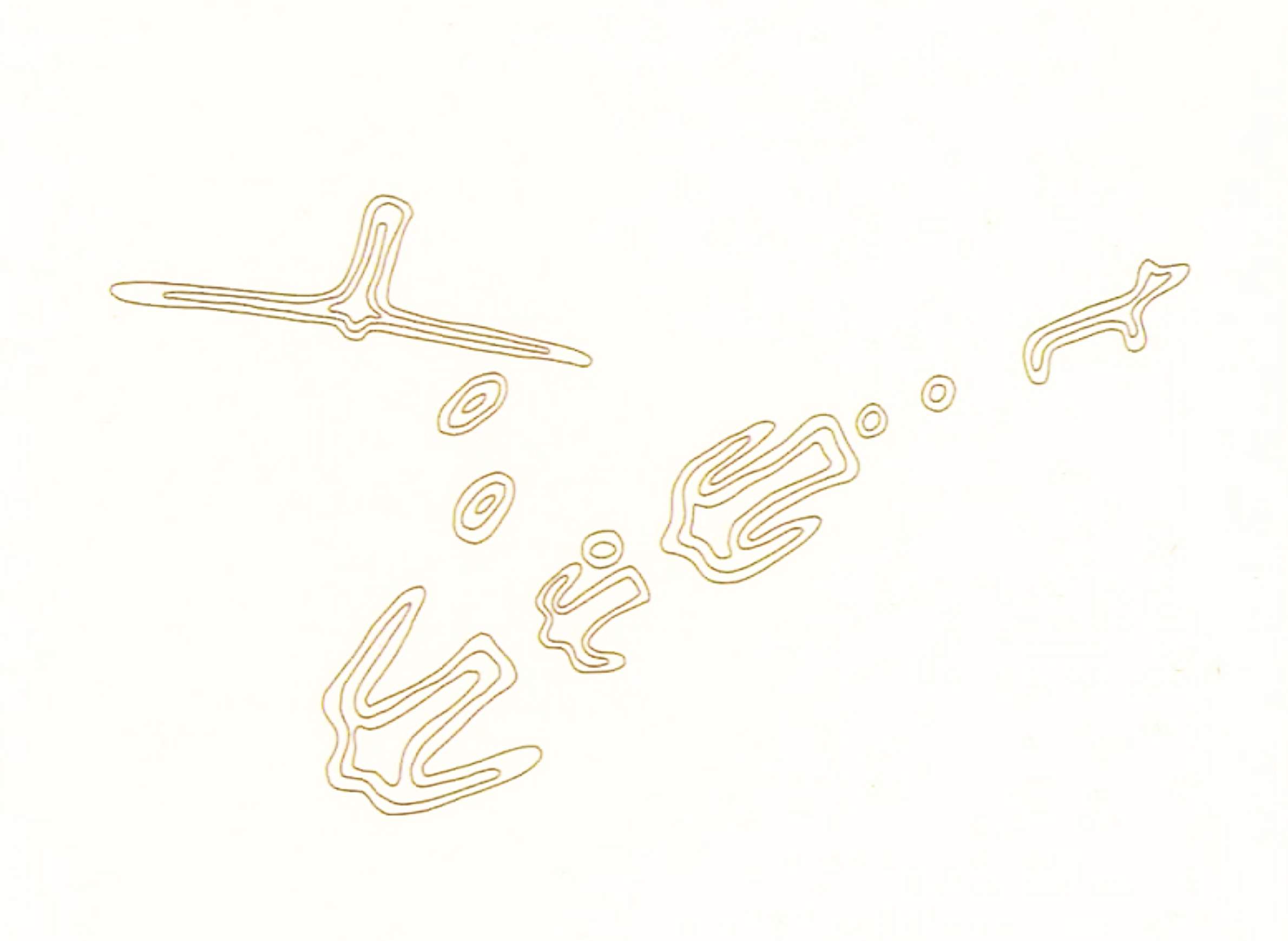

- Wisconsin's effigy mounds are mostly concentrated in the southern part of the state, with Madison right in the middle of the hot spot.

- Effigy mounds are burial sites made of earth and are common in Wisconsin's landscape. Many were constructed in the shapes of like animals and spirits. Other mounds that do not depict specific figures have conical or linear shapes, and are also found in Wisconsin. Other mounds can serve to define a specific area, such as the Whistler Enclosure in Waushara County, which likely marked a space for dancing and ceremonies. Another variation in the style of mounds is the Panther Intaglio in Fort Atkinson, which is an indentation in the ground that fills up with water when it rains.

- Some animals represented in mounds are also totems of individual Ho-Chunk Nation clans, which may indicate which groups the buried people belonged to, or which had power in a given geographic area.

- Mounds bear the stylistic variations of their creators, even if they represent the same creature. Tracking shapes and styles offers clues as to how specific groups or individuals were distributed around the region.

- More often than not, effigy mounds occur in groups along with other kinds of mounds.

- A clay mask and a sculpture of a head are the only representational portraits that have been found of the native people who built Wisconsin's mounds.

- Most effigy and linear mounds were built by "Late Woodland Period" people, between A.D. 750 and 1200, Rosebrough said.

- It's not clear why mound-building ended. Rosebrough believes the expanding cultural and trade influence of the people of Cahokia, a Native American city located near St. Louis in present-day southwestern Illinois, may have a lot to do with it.

- During the 1800s, European-American archaeologists assumed indigenous people did not build the mounds and attributed attributed them to a nebulous race of "mound-builders." Excavations of these mounds in the late 1800s revealed native artifacts and skeletal remains, settling the debate.

- More than 3,000 effigy sites, that archaeologists know of, once existed in Wisconsin, but fewer than 10 percent of those remain.

Key quotes

- On why mounds are almost always near major water sources. "The path of the dead was said to begin in water."

- On the variations among effigy mounds in Wisconsin: "With each succession, funerary ritual and mound rituals changed just a little bit. The effigies were a major innovation, and they appear to have kind of turned mounds inside out."

- On what mounds reveal about power and social order within ancient communities: "If you're in an effigy mound, you're more likely to have that mound to yourself. You're also less likely to have suffered a broken bone or serious injury in your life. If you're in a conical mound, chances are you're sharing it with one, two, three, four, maybe more, other people, up to 50 in some cases, and you probably went in sometime after your death as a bone bundle, not right away. Now, that would imply that the folks that went into effigy mounds have a higher status than the folks that went into the conical mounds."

- On the importance of the mounds to Native Americans today: "Each mound is a unique work of art and a unique representation of ancient belief systems, and each is a sacred place to today's native peoples and to others who respect the history and honor those who came before."

- On what excavations of mounds have turned up besides human remains: "Inside, you're not going to find much in the way of artifacts. Out of all the effigy mounds ever opened, we've got reports of four pots, that's it, a handful of stone tools...and then, from time to time, much more common, clusters of burned stone, not burned inside the mound, but burned someplace else and then gathered and placed in the mound. These may represent light and fire and heat to accompany the deceased."

- On how effigy mounds are just the tip of the iceberg: "You can see the mound, but what you're not seeing is everything that goes with it — the ritual that went into its construction, the ritual that took place around it, the belief, the faith, associated with that ritual, the political wrangling and tussling in between leaders and their followers."