Another Special Elections Fracas And The Question Of Representation

For the second time in as many years, Wisconsin's gears of democracy have slipped and slowed on the questions of how and when a special election would be set by the governor's office. Calling these irregular and often unexpected votes for seats in the state Legislature and occasionally Congress has been a fairly mundane, run-of-the-mill matter for decades. But two quite different governors set special election dates that would end up being confusing, controversial and even litigious.

The first governor was Scott Walker, a Republican who was in his seventh year in office when his actions — or rather, inaction — set off a court battle over the state's special election law.

In December 2017, Walker appointed two Republican state legislators to his administration. The resignations of Sen. Frank Lasee of Senate District 1 and Rep. Keith Ripp of Assembly District 42 went into effect Dec. 29, 2017. However, Walker had no plans to call special elections and rather opted to leave each seat vacant until the following general election on Nov. 6, 2018.

Walker argued that, in accordance with state law, he did not have to call a special election for the two legislative seats because the resignation dates did not fall within the same year of a regularly scheduled election. But on Feb. 26, 2018, voters from both districts filed a lawsuit against the governor asserting that he was not following the letter of the law. After a furious week of litigation, the courts ordered Walker to call elections. He complied, setting a special election for June 12, 2018.

Had Walker gotten what he originally wanted, 312 days would have elapsed between the time of the resignations and the subsequent general election.

But given the court order, that time span instead ran 165 days.

The second governor is Tony Evers, a Democrat in his first year in office when the initial date he selected for a special election to replace U.S. Rep. Sean Duffy, a Republican who announced in August 2019 that he would resign in September, evoked complaints about its timing. A conflict between state and federal law led him to ultimately set a much later date. This special election will leave a Wisconsin legislative seat open for the longest span of time in modern state political history, a situation the governor expressly tried to avoid.

Setting a date as soon as possible

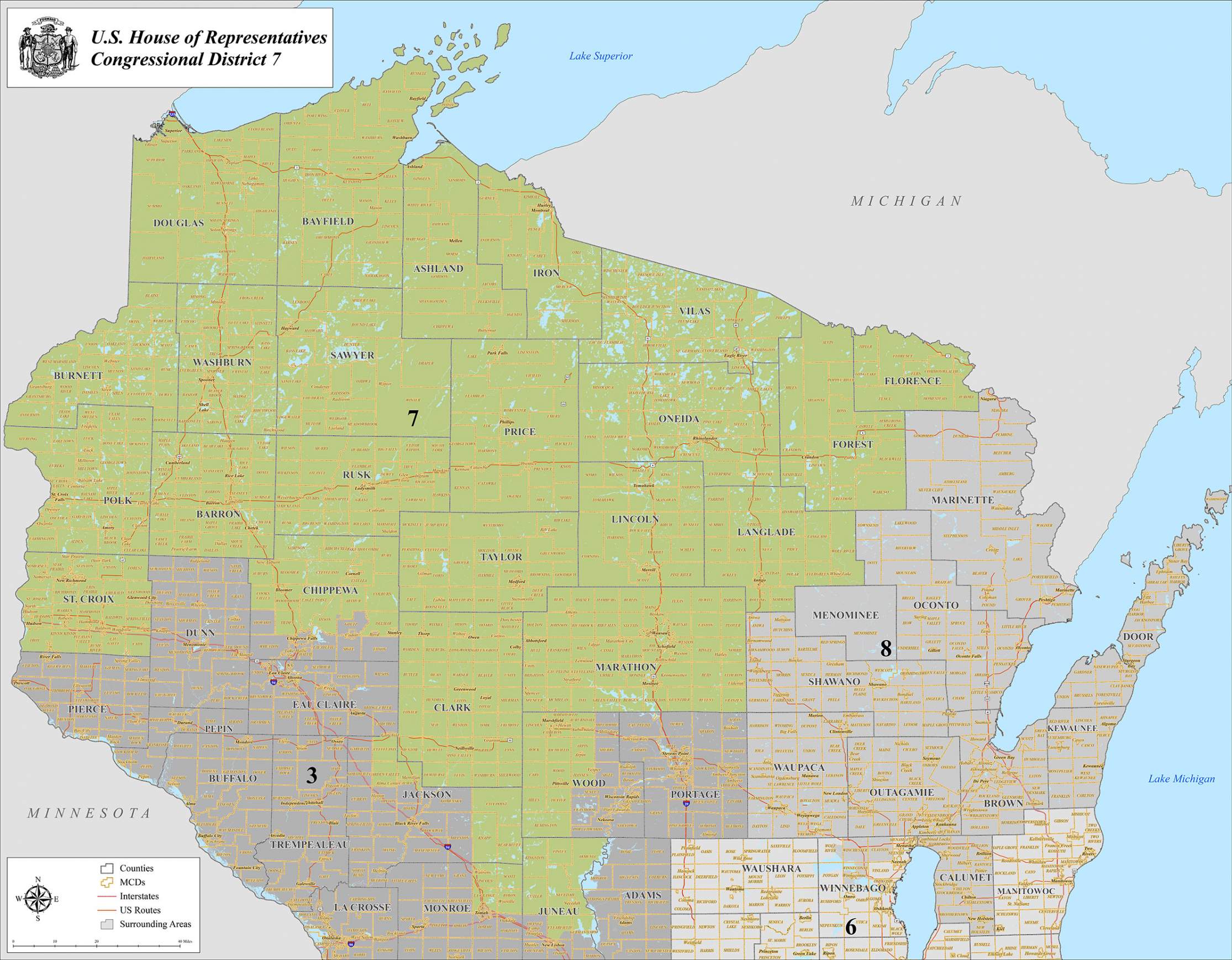

Wisconsin will hold a special election for the 7th Congressional District on May 12, 2020, but getting to that date was no simple task.

On Sep. 23, 2019, Gov. Evers called a special election to fill the vacancy for Monday, January 27, 2020, with its primary to be held Monday, December 30, 2019.

Evers set these dates the same day Duffy's resignation went into effect, the earliest point at which the governor was able to do so.

The governor said he went with these dates to expedite the entire process. In a press release, Evers said, "the people of Wisconsin's 7th Congressional District deserve to have a voice in Congress, which is why I am calling for a special election to occur quickly."

The earliest date possible for the election would not have been tenable, though. State law dictates that special elections for federal office must be held at least 92 days from the governor's original order, meaning the earliest a primary could have been held was Christmas Eve, which would pose obvious complications.

The dates Evers landed on had several unique aspects, though. Both election days fell on Mondays, which would have been highly unusual. They were set this way to avoid holding the primary on New Year's Eve. However, Dec. 30 is the final night of the Jewish holiday Hanukkah in 2019.

Both Republicans and Democrats were quick to denounce these dates.

Republicans accused the governor of being motivated by partisan intentions, with the Wisconsin GOP Twitter account suggesting he wanted to avoid potentially high Republican voter turnout if the special election were to be held alongside the state's presidential primary in April. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republican from Rochester, also criticized Evers' decision because of the conflict with Hanukkah.

U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan, a Democrat who represents Wisconsin's 2nd Congressional District, also criticized the original date, saying that scheduling an election any time around the winter holidays would lead to low voter turnout. Additionally, the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, a liberal-leaning nonpartisan watchdog group, argued that holding an election on a Monday of a holiday week would result in low turnout.

Barry Burden, director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said objections over partisan motivations were predictable.

"Setting the general election in the 7th District on the same day as the April 7 spring election seems sensible as a way to contain administrative costs and encourage voter turnout, but it could also be viewed as favoring one party or other," he indicated in an email to WisContext.

"Almost any dates selected by Gov. Evers would be have been seen as partisan by someone."

Since the spring election on April 7 will include what are expected to be a competitive Democratic presidential primary and state Supreme Court race, turnout across the political spectrum will be meaningful.

If the special election were held that day, Burden explained, "Republicans might accuse Evers of trying to boost the Democratic congressional candidate because heavy Democratic turnout expected in the presidential primary could provide the candidate with additional votes. On the other hand, Democrats might worry that having the elections on the same day would jeopardize their chances of a liberal candidate winning a Supreme Court race because the 7th District election is likely to favor a Republican candidate and thus bring out more GOP voters."

On balance, what's the substance of either speculation?

"Weighing both possibilities, the benefit of a same day election is probably greater to Republicans than to Democrats, but it is possible to see bias in either direction," Burden said.

However, it wasn't just partisan politics that precluded the original dates the governor set.

A federal reset

On Oct. 1, Gov. Evers announced he would drop the special election dates he originally set and select new dates. But he didn't do so immediately, as his options were unclear owing to conflicting language between state and federal law.

Reid Magney, spokesperson for the Wisconsin Elections Commission, explained how state law was only one piece of the puzzle for this particular special election. Because Sean Duffy was a member of Congress, Evers also had to take into consideration federal law when setting the dates for both the primary and special election. In this situation, the federal law mixed with the state's like oil and water.

The federal law relevant to setting legal special election dates is known as the MOVE Act. It was signed into law in 2009 by then-President Barack Obama, and its aim was to help citizens and U.S. military personnel abroad cast their votes. The law requires that absentee voters in federal elections have at least 45 days to receive and return their ballots, Magney explained.

This law prompted Wisconsin to schedule its regular partisan primaries one month earlier than in the past, but not every aspect of the state's elections caught up when the change occurred.

"What didn't happen [were] concurrent changes to the [state] law about how to have special elections when it's a federal election," Magney said.

This requirement left the Evers administration between a rock and a hard place. While there have been well over a dozen state special elections in Wisconsin since 2009, Duffy's resignation prompted the first federal special election in the state since the MOVE Act became law, Magney said.

On Oct. 18, Evers selected a new date: May 12, 2020, with the primary to be held on the regular spring primary date of Feb. 18.

A longer than anticipated gap

The Evers administration has indicated the governor's original selection of special election dates was meant to reduce the length of time residents of the 7th Congressional District would go without representation in Congress. From the point of Duffy's resignation to the initially proposed special election date, this gap in representation would have lasted 126 days, a period that would have fallen near the upper end of the typical length of time in Wisconsin between when a seat becomes vacant and a special election is held.

But given the delay, the date of the special election on May 12 marks the longest period between a vacancy and election in modern Wisconsin political history, at 232 days.

So why not — as some suggested — set the special election for the already scheduled spring election on April 7?

The Evers administration defended its actions that ultimately resulted in this later election date.

"The original dates were selected to ensure the people of the 7th Congressional District have representation in Congress as quickly as possible," Evers' spokesperson Britt Cudaback wrote in an email to WisContext.

"Governor Evers appreciates that unexpected special elections can put a strain on the system, especially for our local election administrators, which is why he chose to align the special election primary with the existing spring primary."

Yet at the same time, the governor set the general special election more than a month after the already-scheduled election day.

UW-Madison political scientist Barry Burden noted there are practical concerns associated with this date that could be both positives and negatives for local elections officials.

"On a practical level, the April 7 ballot is likely to be a long one due to the large number of Democratic candidates running for president. Election officials in the 7th District might prefer not to make the ballot longer and more complex by adding a special congressional election to it," he said.

"At the same time, having a congressional election just five weeks after the Supreme Court election and presidential primary is a hassle for election officials who may need to juggle ballots for both dates simultaneously and confuse voters who will be facing the third election in 12 weeks."

State law precluded the possibility of primary and general special election dates for the 7th District seat that would have both fallen within the first few months of 2020.

"No special election may be held after February 1 preceding the spring election unless it is held on the same day as the spring election, nor after August 1 preceding the general election unless it is held on the same day as the general election, until the day after that election," reads the special elections statute.

The original Dec. 30, 2019 and Jan. 27, 2020 dates set by Evers would have avoided that Feb. 1 deadline.

When asked why Evers didn't order the general special election in conjunction with the April 7 spring election, the governor's office did not offer a direct answer.

In the wake of this imbroglio, bipartisan legislation was introduced in both the state Senate and Assembly that would defray special elections costs. Cudaback said the governor supported their passage, along with efforts to align state and federal laws on special elections.

Ultimately, the intentions of both Scott Walker and Tony Evers were not to be. Had Walker had his way, two state legislative seats would have remained open for close to one year, while had Evers had his way, one congressional seat would have been filled within a few months.

The value of representation

While the 7th Congressional District special election dates comply with the law, the extended amount of time between Sean Duffy's resignation and the special election has more than just legal implications.

The scheduling of special elections can serve many purposes, Barry Burden explained. There's also the matter of constituents in a given district being represented — or not — in representative government.

Special elections can often serve as test runs for political parties. It gives them a chance to see how they might fare in a general election and is an opportunity to motivate their bases, Burden said. And in a competitive state like Wisconsin, these stakes are especially amplified.

Burden explained how many factors can influence the amount of time that's necessary before a special election.

"The need for representation is clearly a concern, but so is giving candidates an opportunity to gather their campaigns," Burden said. "It wouldn't be possible to schedule an election just a month or two from the time [a seat] becomes vacant because it wouldn't give potential candidates time to decide whether they're in or out and for them to gather signatures and hire staff and begin to do fundraising."

At the same time, Burden said a lack of representation is a "real concern" until the 7th District seat is filled.

"Although Rep. Duffy's former staff are able to process basic requests for assistance from constituents, residents of the district do not have a specific voice speaking for them in the House of Representatives," he said.

While the absence of a voting member of the House in that seat is not likely to have an impact on roll call votes given how high-profile issues typically fall along partisan lines and Democrats hold a large majority in the chamber, the constituents of the 7th District will nevertheless have less influence when it comes to district-specific issues.

"The more relevant concern is not having a person to bring a voice to issues that matter in particular to residents of the district," Burden said. "An example of this kind of issue is the limited availability of rural broadband service. Rep. Duffy was particularly attuned to rural broadband because of the concern expressed by residents who lack it."

The victor of the special election on May 12 will serve in office until the end of the term. The seat will be up again in the 2020 general election on Nov. 3.

Editor's note: This article was corrected to clarify the state law requiring that a special election may not be held after Feb. 1 unless it is on the same day as a spring election.