The Costs Of Taking Broadband The Extra Mile In Wisconsin

As Wisconsin struggles to grow private-sector jobs, there is potential to expand telecommuting work outside urbanized areas of the state by improving broadband connections. As it stands, about 13 percent of Wisconsin's population lacks access to high-speed internet connections, according to a 2016 progress report from the Federal Communications Commission.

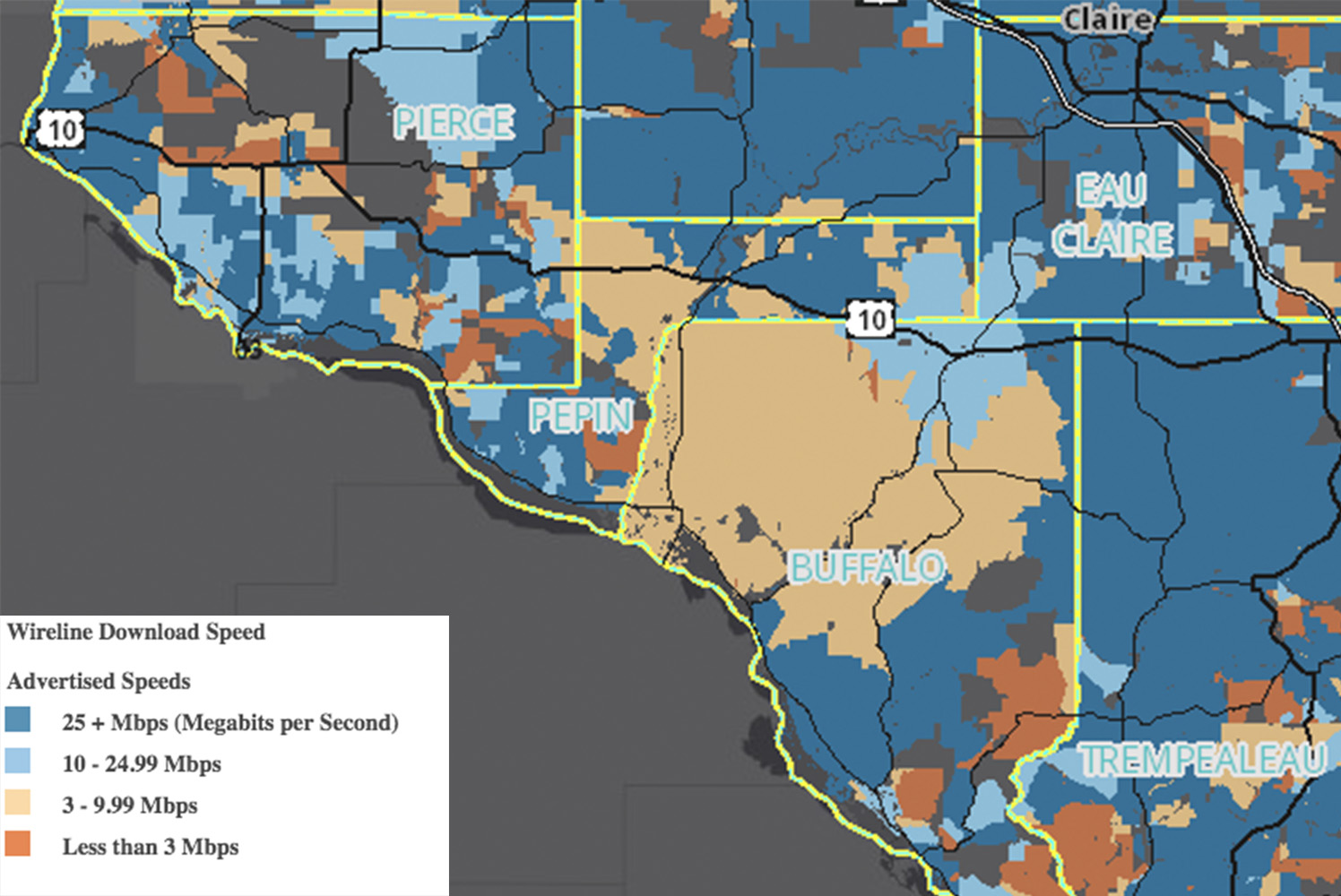

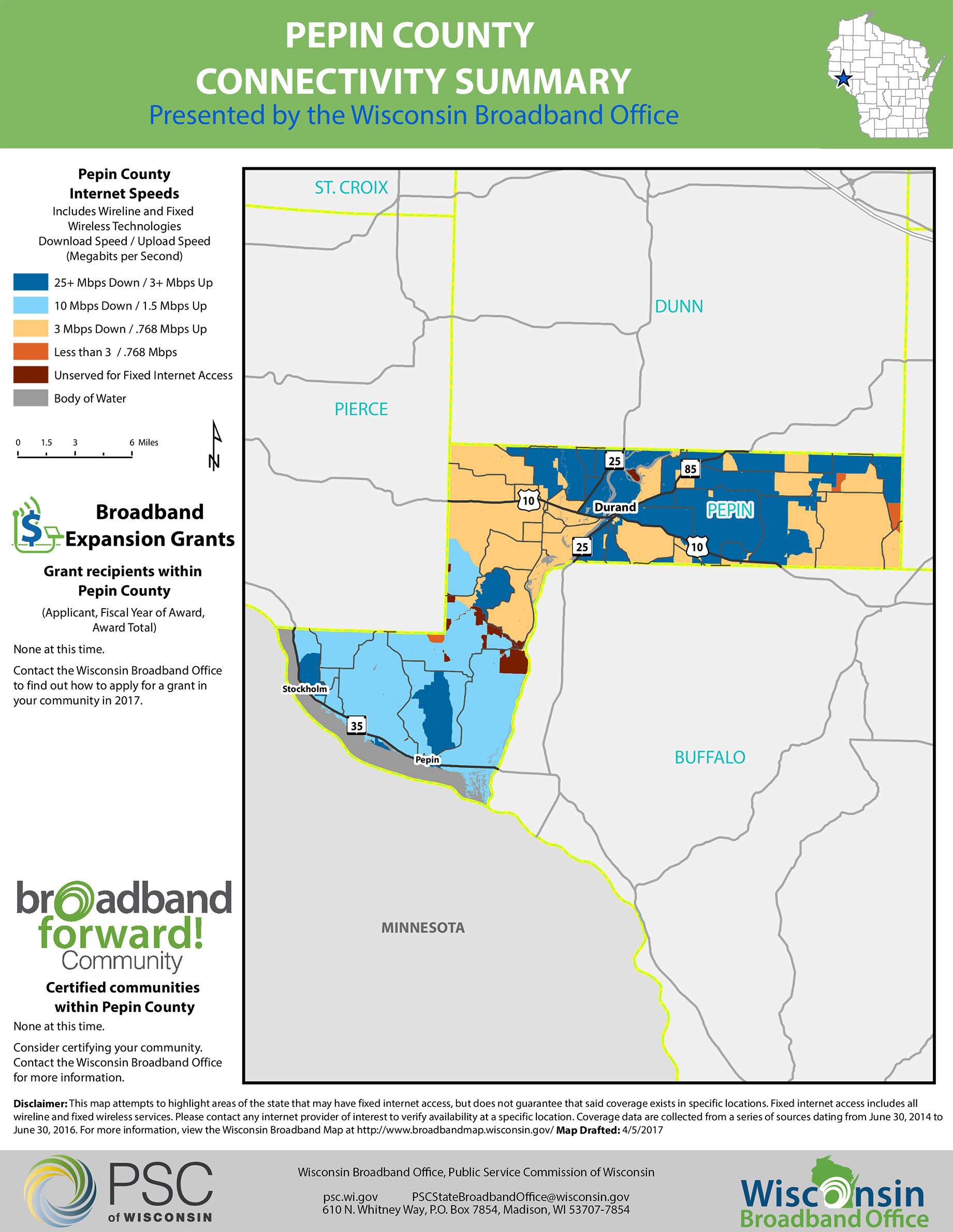

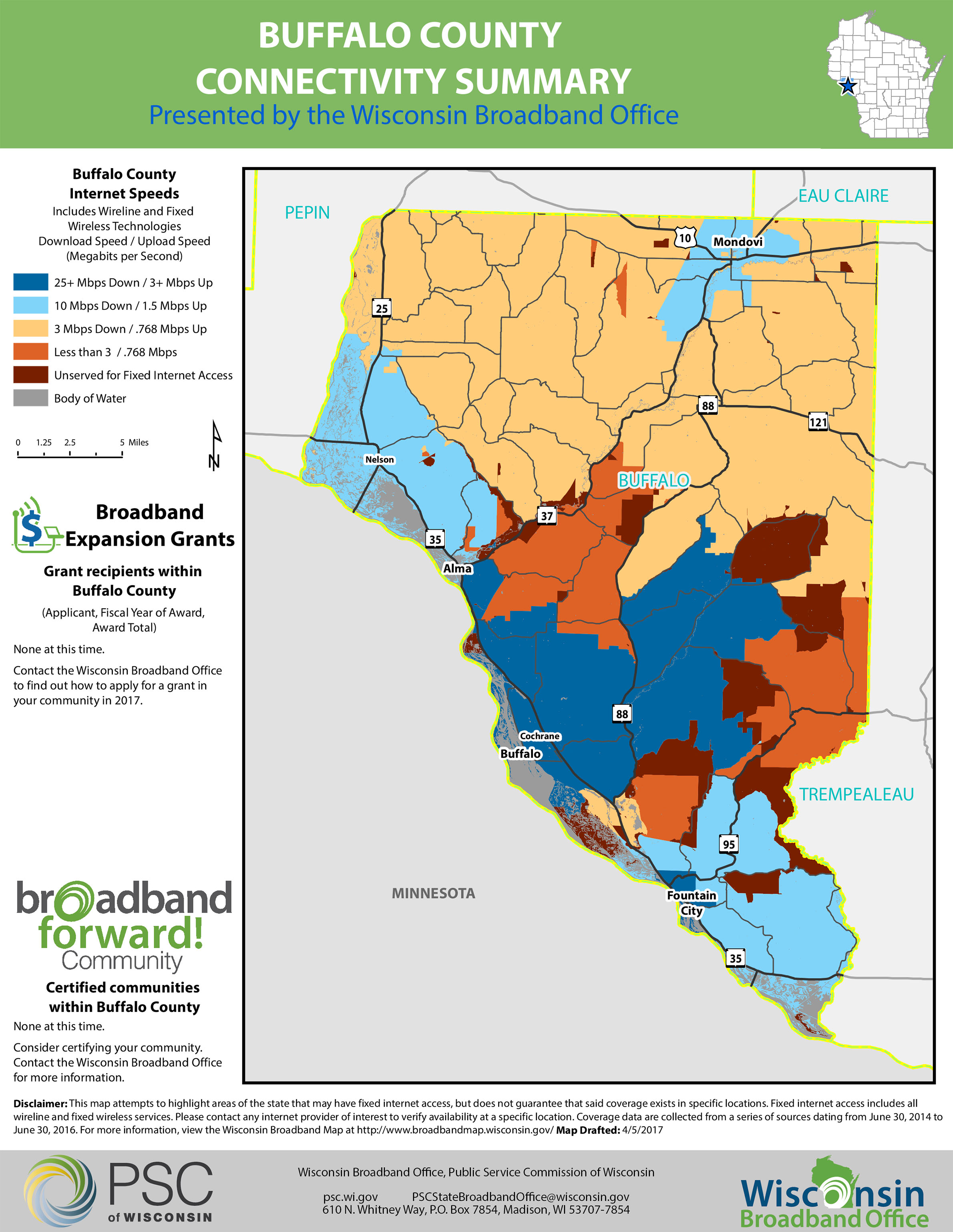

Across large swaths of Pierce, Pepin and Buffalo counties in western Wisconsin, internet service providers offer only relatively low-speed connections. The picture is similar across many other rural areas, at least according to a map created by the Wisconsin State Broadband Office — some broad swaths of high-speed connections, but heavily speckled with areas where download speeds are lower than 10 or even 3 megabytes per second.

Why so many places are broadband-deprived in a digital era essentially comes down to age-old problems of infrastructure and cost.

Say a city's drinking-water utility is weighing whether to extend services to a small, new subdivision on its outskirts. Extending a water main there could cost millions, and in return the utility would gain only a few new households paying water rates, really not enough to get a return on that investment anytime soon.

The city of Racine's water manager, Keith Haas, described that very issue in to WisContext in 2016: "It's not worth me putting in a million-dollar water main for $500 in revenue every year," he said.

With broadband, the specific numbers might be different but the problem is the same: Revenues from a certain group of customers might not compensate for the costs of making them customers in the first place.

In a June 9, 2017, report on Wisconsin Public Television's Here And Now, Pepin County resident Janice Quinton explained how a broadband connection enables her to work remotely for an interior-design company in the Madison area, while her husband works locally as administrator of the Pepin Area Schools.

Gina Tomlinson of Cochrane Co-op Telephone, which also provides internet services in Buffalo County, summed up the cost challenges of building broadband infrastructure this way: "In rural areas, it’s very hard to be able to afford to go out to that one customer that has a mile, mile-and-a-half driveway and they're ten miles out from the central office, which is where all the electronics sit."

The company is using a loan from the USDA's Rural Utilities Service to help bridge that gap between upfront costs and the modest or slow return on broadband investments.

Defining "rural" areas isn't always a simple matter, including when it comes to broadband infrastructure.

Critics of recent state-funded efforts to expand broadband access question whether they will target the neediest areas. When passing a bill in May 2017 that would allocate $35 million to broadband expansion, the Wisconsin Assembly declined to incorporate a federal definition of rural into its language.

The Wisconsin broadband office's map shows which areas are eligible for broadband grants in fiscal year 2018, and it covers vast areas of the state, not all of them sparsely populated or underserved.

State Sen. Kathleen Vinehout, a Democrat from Alma, which is located in Buffalo County, even called Republican-backed rural-broadband legislation "false advertising."

However, the state's broadband efforts have made some impacts where rural residents need them. Lafayette County is using an $86,000 state grant in an effort to extend wireless broadband access to all county residents by 2018.

In addition to its economic impacts, broadband-enabled telecommuting might also help less-populated areas retain and attract more residents. It would allow people to pursue lifestyle benefits they seek in rural places — like the small-town atmosphere that attracted the Quinton family to Pepin and the beautiful scenery along the Mississippi River — without passing up job opportunities that would usually require moves or long commutes.

Between now and 2040, many of Wisconsin's rural counties are expected to lose population as the state's urbanized areas grow. One of the places demographers project to lose population is Buffalo County. A couple of factors converge there: A 2015 report from the state Department of Workforce Development indicated that more than half of the county's employed residents commute outside of it to work, many across the river to Minnesota. The state's broadband map also shows almost the entire northern half of Buffalo County relegated to internet download speeds of under 10 megabytes per second.

Limited internet access is not the reason for all that commuting from Buffalo County. But it suggests, though, that greater connectivity would enable more of its residents to start their own businesses or work remotely.

The decline of rural manufacturing and the consolidation of farms will likely have a lot to do with population projections.

Speaking to Here And Now, Ricky Rolfsmeyer, executive director of the rural-development nonprofit Wisconsin Rural Partners, and Don Sidlowski, founder of the Northwoods Broadband Economic Development Coalition, both shared their concerns over that trend.

Sidlowski said that expanded broadband access would make it more likely for young people raised in rural Wisconsin to stick close to home.

"If they decide to go off to technical college or four year school they can come back, work from home if they start a business themselves. Or work from a remote location for their employer," he said. "Those kids are going to be more encouraged to want to stay right here, closer to home and pursue their careers here in Wisconsin."

Rolfsmeyer made a similar point — that broadband could do a lot to "keep rural people rural."

"Broadband is one of the greatest tools we have to help rural people stay in their rural communities and be engaged," he said.