Historic Photography Reveals Depths Of Civil Rights Struggle In Milwaukee

When thinking about the African-American civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s, the first images that often come to mind are from southern states: federal troops enforcing school desegregation, bus boycotts and lunch counter sit-ins, Freedom Riders registering voters, marches in Washington, D.C. and Selma, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s leadership through the era. But while much of the nation's eyes were turned toward the South, struggle for equal opportunities and accompanying social unrest also reached a boiling point in northern states, particularly in cities like Chicago, Detroit and Milwaukee.

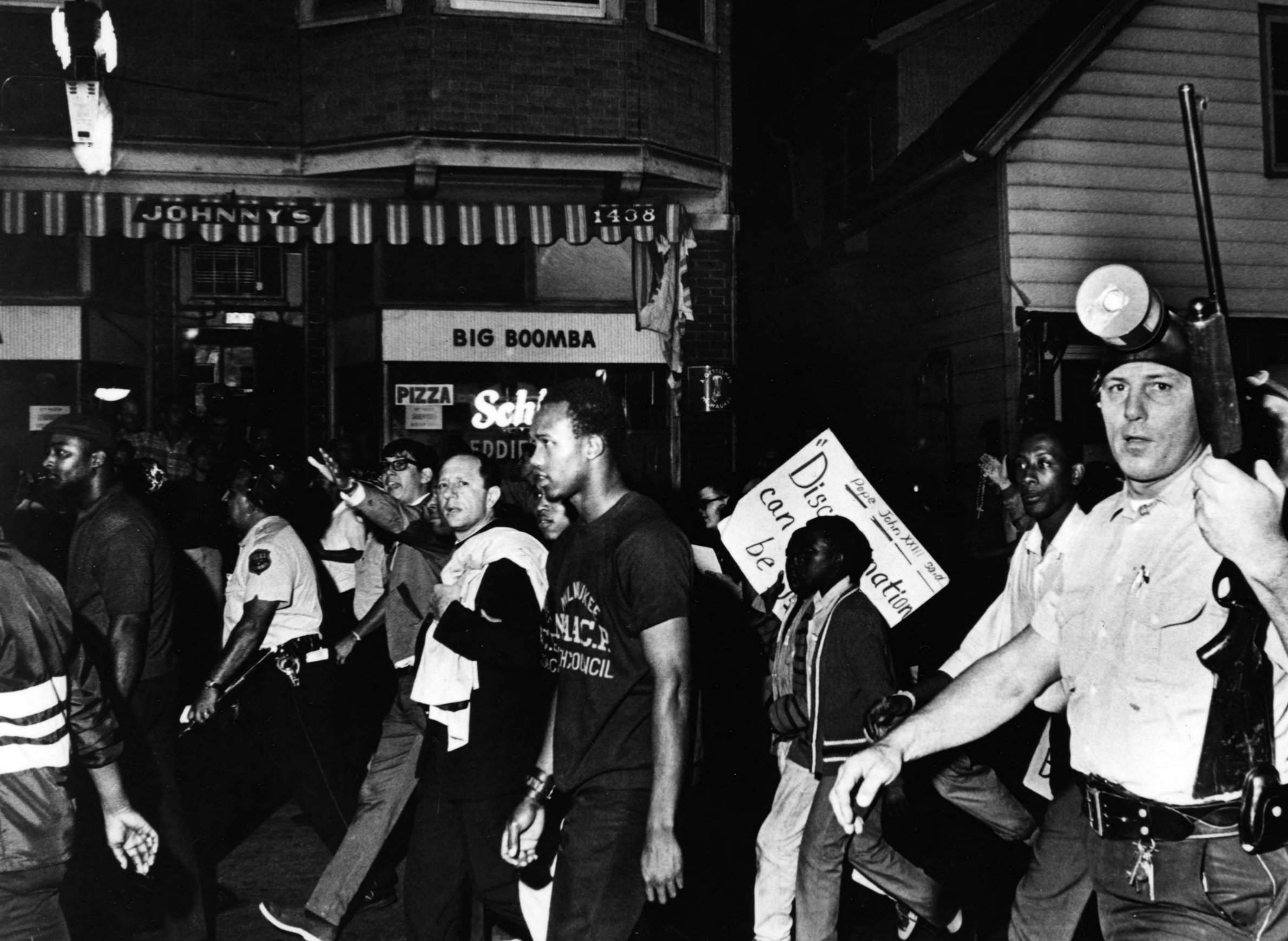

From the summer of 1967 through the spring of 1968, a group of teenagers in the NAACP Youth Council and their supporters marched for 200 consecutive nights in support of open housing legislation in Wisconsin’s biggest city. The Milwaukee open housing marches, also called the "March on Milwaukee" and "Miracle in Milwaukee," protested racial discrimination in housing in the city.

This localized movement in Milwaukee was a relatively unsung contribution to the broader struggle for civil rights and helped spur support for passing the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included the Fair Housing Act prohibiting discrimination for home renters and buyers. One of the march's leaders was Rev. James Groppi, a white Catholic priest who encouraged the group to keep marching against segregation despite dangers they faced from thousands of counter protesters.

Madison-based Historian Mark Speltz spent a decade writing and researching the civil unrest in northern cities for his book, North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South. Released in 2016, the book delves into the civil rights struggle as experienced in cities outside the South. He shared photos from demonstrations in Milwaukee and elsewhere in a Feb. 15, 2017 presentation at the Wisconsin Historical Museum, which was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place.

Speltz's interest in the civil rights movement in northern states took shape while he was a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He began researching and collecting images from the Wisconsin Historical Society's Social Action Collection, which includes many photographs from the civil rights movement that had never been previously published.

"I had always been moved by the compelling images that I saw in my history books, that I'd see in TV and in magazines," Speltz said. "So, I dove into ... all of the photographs and materials that they began collecting during the 1960s."

Key facts

- The open housing marches in Milwaukee were covered by both local and national media outlets. There were two African American weekly newspapers in the city at the time, the Milwaukee Star and the Milwaukee Courier (which is still publishing). Speltz noted that these papers were able to take a particularly unique angle with their coverage since many of the reporters and photographers had grown up in the community. National outlets like Ebony Magazine and Jet also covered the Milwaukee marches, informing their audiences about civil unrest was indeed happening in the north.

- Most of the media photographers assigned with covering the various civil rights protests were younger and newer to their jobs These photographers often worked late-night and weekend shifts, which is often when the protests took place. As a result, these young photographers gained unique experience in their field.

- In protests across the nation, many participants didn't want to be photographed for fear of retribution. In some images, people can be seen purposefully hiding their faces behind signs in order to avoid recognition. Moreover, police officers often lined the streets of protests and armed themselves with cameras to capture images to determine the identities of the demonstrators themselves.

- Through his research, Speltz found that there really wasn't much difference between the photographs taken in northern states and the photographs taken in the South. However, he found that there was a difference in how the photos were used in the media. Often in northern cities' media outlets, like those in Milwaukee, protest photographs were buried in attempt to downplay any local concerns. Coverage of the peaceful protests were often cast aside in order to feature the attention-grabbing and sometimes-violent movements of the south.

- In North of Dixie, Speltz used work work from 50 different photographers, photojournalists, artists, amateurs, police and FBI photographers. Twenty-five different cities from across the country are represented in the book.

- In 2007, while Speltz attended graduate school in Milwaukee, the city celebrated the 40th anniversary of the marches. This celebration contributed to the spark that lit the flames for the book. Milwaukee began the 50th anniversary celebration of the march on August 28, 2017 with events planned for for the following 200 consecutive nights. Dubbed "200 Nights of Freedom," the celebration seeks to honor the original marchers’ efforts and to build connections across different networks in the city.

Key quotes

- On the intensity of the Milwaukee marches: "It was an incredibly tense time. This was the second night, and marchers were met by thousands of counter-protesters. People from the sidewalks threw bags of urine, rocks, firecrackers, bottles — it was an incredibly dangerous time."

- On how the photographers felt covering the at-times dangerous marches: "They told me how dangerous it was, how they were just learning to cover these demonstrations, and how they had to protect themselves. … [P]eople had protective gear on because they, too, were getting hit by the bottles and the rocks."

- On local Milwaukee photographers covering the marches: "They had a particular unique angle. They were in the community. The photographers grew up in the neighborhoods. They were educated in the local schools, learned photography through the local programs, and then worked in their community to document both the community functions — the business openings, funerals, those types of celebrations around town — but also social justice issues, like marches."

- On the calling the marches the "Miracle in Milwaukee": "You might wonder, 'Why would they use the word miracle?' But it was an interracial civil rights demonstrative group coming out of a church, led by a white priest ... [n]ot always using nonviolence. They would contest that they could use violence if acted upon. And that was not where the Civil Rights Movement was at. Interracial groups were on their way out; Black Power was on their way in. A white leader of a group of youths was not common. So, they were sort of the last hope for that type of opportunity, that type of movement, and they were called the 'Miracle in Milwaukee.'"

- The goal of North of Dixie: "The goal of the book is to make visible lesser known, but equally inspiring stories from L.A. to Harlem, from coast to coast. [The] book features 100 photographs taken from the late 1930s into the 1970s."