The (Not So) Secret Lives Of City-Dwelling Coyotes And Foxes

Red foxes and coyotes are a curious bunch of carnivores. When born into packs that have abandoned their species' typical habitats, these highly adaptable canids quickly take to quietly hunting and scavenging among the parks, pavement and refuse on offer in urban and suburban communities across Wisconsin. Now, scientists studying coyotes and foxes living in the state's capital are beginning to unravel how these city dwellers differ from their country counterparts, sometimes in surprising ways.

Led by wildlife ecologist David Drake at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, these researchers have observed behavior that suggests the critters may be more prone to peaceful coexistence than are their highly competitive peers in the state's hinterlands. This difference is despite the reality that, like their human neighbors, urban canids live in closer proximity to each other than they typically would outside the city.

Drake described the observations in a March 30, 2016 talk on the UW-Madison campus recorded for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place. They are among a slew of new information that has come out of Drake's UW-Madison Urban Canid Project, a long-term research and monitoring program that relies on a mixture of tracking techniques and technology and crowdsourced resident observations to shed light on the secret lives of Madisonian canids.

"Typically, the distribution of fox on the landscape is completely dictated by where coyotes are or they are not," Drake explained. "And, typically … out in the countryside, if coyotes can catch [a] fox, they will kill that animal, not to eat it necessarily, but to limit competition."

Meanwhile, Drake and his colleagues have observed coyotes (Canis latrans) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) seemingly coexisting with very little conflict. In one instance, a coyote and a fox wearing radio collars were observed via location data to be foraging in close proximity to one another for more than an hour. In another case, coyotes were visually observed scavenging a rabbit carcass from a fox den (peaceful coexistence does not necessarily equate to polite behavior) while the foxes remained in the vicinity.

"This behavior continued for close to one month, with no attempts from the red fox family to relocate to any of several available nearby dens," Drake and his colleagues reported in a January 2018 journal article based on their observations.

Such behavior between the two species is unusual, and it hints at just one of several potential ways the widespread carnivores are adapting to urban environments, where resources are aplenty.

"What we're looking at here in the city, and our working hypothesis, is that these animals were actually able to get along," Drake said in his 2016 talk.

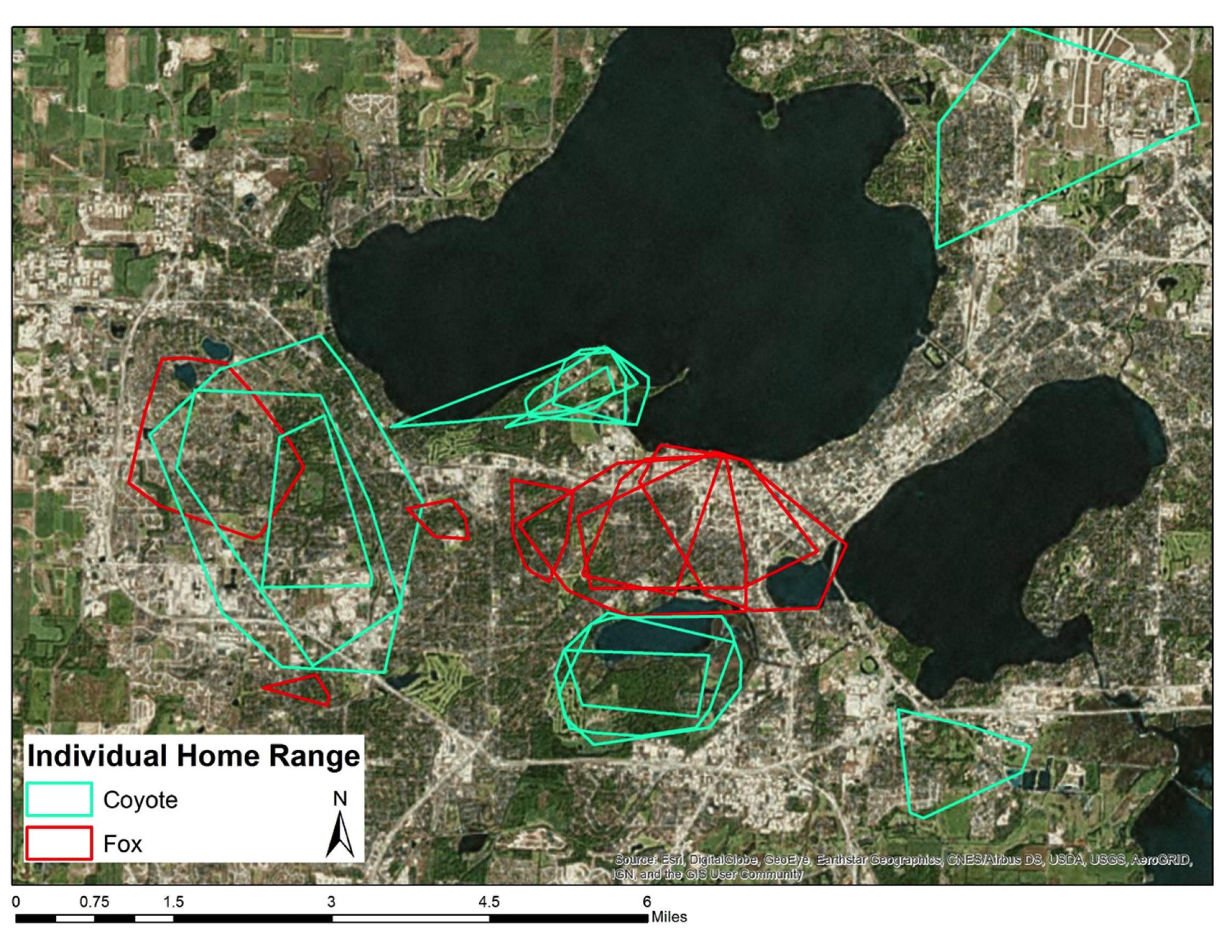

And yet, urban coyotes and foxes behave similarly to their rural counterparts in a lot of ways, according to Drake. They generally remain territorial, especially within species, and they don’t often stray into each other's claimed spaces let alone come into direct contact.

Additionally, coyotes prefer to stick to cities' large natural areas, such as the UW Arboretum and Owen Park in Madison. On the other hand, foxes tend to venture into neighborhoods more often. Drake's observations, along with those of other urban canid researchers in Chicago and elsewhere, also confirm that both subsist on strikingly similar diets to those of their peers in wilder habitats, including rabbits and small rodents.

At the same time, these canids have more abundant options, and they aren't above scavenging from a backyard compost pile or other refuse. And, Drake conceded, coyotes will attack unattended small outdoor pets and fowl, though the incidents are fairly rare.

The abundance of resources that may ease the tension between urban coyotes and foxes do come at a cost, though, as the canids must also contend with threats that accompany city life, leading with cars. Many of the canids Drake and his colleagues have tracked over the years have met their fates while attempting to cross a road.

In the end, Drake hopes the urban canid project can encourage city dwellers to engage with the natural environments around them and inform decision-making among wildlife managers. With a rapidly urbanizing global society and increasing pressure on wild places, it behooves humans to better understand the animals that share their spaces, he said, which together make up the globe's fastest-growing habitat.

Key facts

- Coyotes and red foxes are widespread in North America and beyond, with the latter being the most widespread carnivores in the world. Both canid species are adaptable to new environments, including urban landscapes.

- Both foxes and coyotes are territorial species that usually live in packs or family groups that share and defend an area from competition from other carnivores. Coyotes are especially territorial, and in natural habitats they are known to kill foxes within their territories.

- Before European settlement, coyotes had a much more limited range in North America, but due to their adaptability and a steep decline in gray wolves, the predators have spread across the continent's rural and urban areas.

- The UW-Madison Urban Canid Project began in 2014. Researchers at UW-Madison have live-trapped and placed radio collars on coyotes and red foxes in the Madison area to better understand where the animals live and hunt. They've also used a mixture of observations from residents and trained students to shed light on the creatures' diets and behaviors.

- Since its inception in 2014, the UW-Madison Urban Canid Project has caught and tracked 20 coyotes and 16 red foxes. With funding through 2021 and Drake's pursuit of additional funding to extend the project, that number is expected to grow.

- Urban coyotes tend to stick to urban green spaces like large parks and natural areas, though they occasionally venture out into more built environments to search for prey. Foxes are more likely to live and hunt in neighborhoods.

- Occasionally, urban coyotes will attack and kill unattended small pets, though this behavior is considered rare. Both coyotes and foxes will also go after backyard chickens and occasionally scavenge among compost piles and garbage.

- The project in Madison is one of several efforts in the United States to monitor urban canids, including the longest running such effort, the Cook County Coyote Project based in Chicago. That research has found that coyotes are so adaptable that packs now live among the skyscrapers and throngs of people in the city's downtown.

Key quotes

- On the ability of both coyotes and foxes to adapt to urban environments: "Because of their diet, general natures and their habitat generalists, they're very easily adaptable to city-type areas like we have here in Madison … [W]hen you think about areas like Madison and a lot of cities, especially that suburban fringe of the city, that fragmented, very scattered landscape is ideal for these animals."

- On the eating habits of urban canids: "The interesting thing about these animals is even though they are living amongst us in this human dominated landscape, a majority, and sometimes a vast majority of their diet is still very natural. It's what you would find them eating out in the countryside or more natural areas. So they'll eat, you know — certainly coyotes in urban areas, we call them the top or the apex predator, they certainly can eat deer, but they really subsist on rabbits, squirrels. We've seen one of our foxes has brought back muskrat, domestic chickens."

- About the specificity of the data Drake and his colleagues collect: "We don't need to know exactly it is in, you know, the back corner of this person's yard. We just need to know it's generally in that yard. So we're not overly obsessed about the specific location, but we do need to be pretty accurate with our triangulation."

- On the different movement habits between red foxes and coyotes in Madison: "The fox are in the very, very developed landscape of the city. The other thing to notice is how tight these movement patterns are for the coyote. The fox, over the course of maybe a couple week period, you know, he's moving four, five, six, seven miles, something like that."

- On a key goal of the UW-Madison Urban Canid Project: "We're also trying to engage the public in order to raise awareness that these animals are in the landscape, educate the public about why they're here, and then increase tolerance because we're not going to ever get rid of these animals, so we better figure out how can we live with these animals."