How Foxconn Can Turn On The Faucet In Mount Pleasant

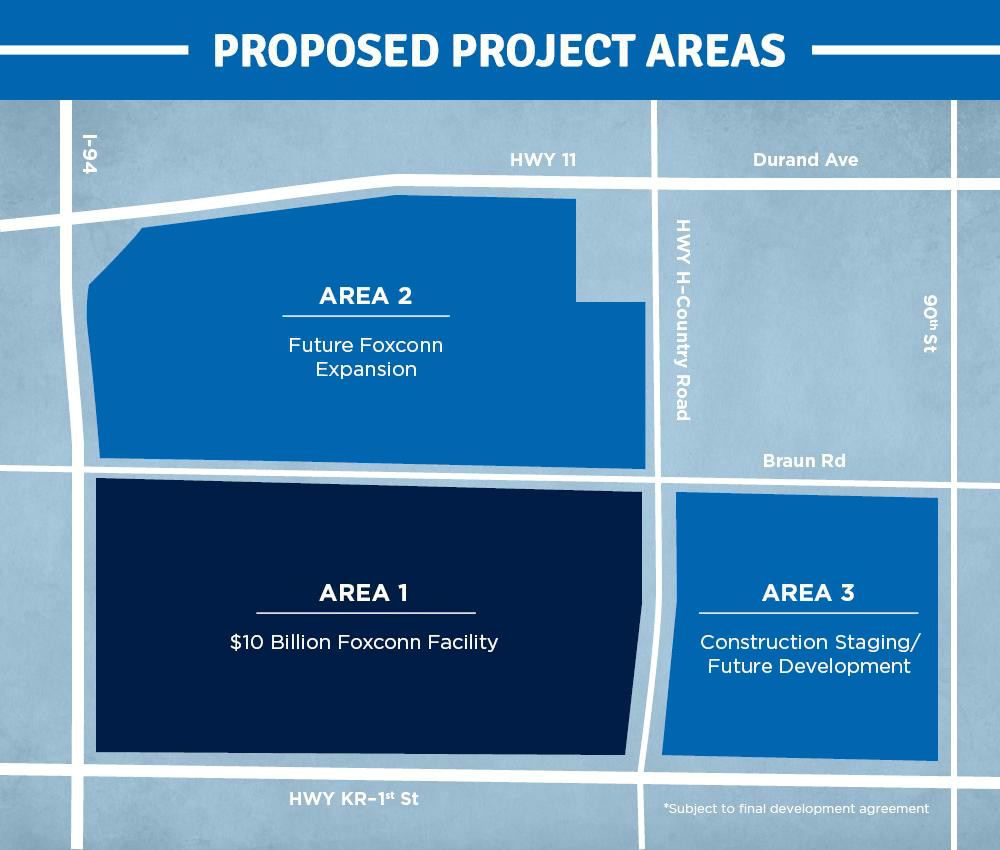

As Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer Foxconn scouted out potential locations for a LCD manufacturing complex in southeastern Wisconsin — eventually selecting a site in Mount Pleasant that's 20 million square feet in size — the company was also thinking about water. Manufacturing electronics on a large scale requires copious amounts of water, and the factory would likely use millions of gallons of it per day if it gets built as planned. That water will almost certainly come from Lake Michigan, and the location of the facility will govern how Foxconn goes about acquiring this resource.

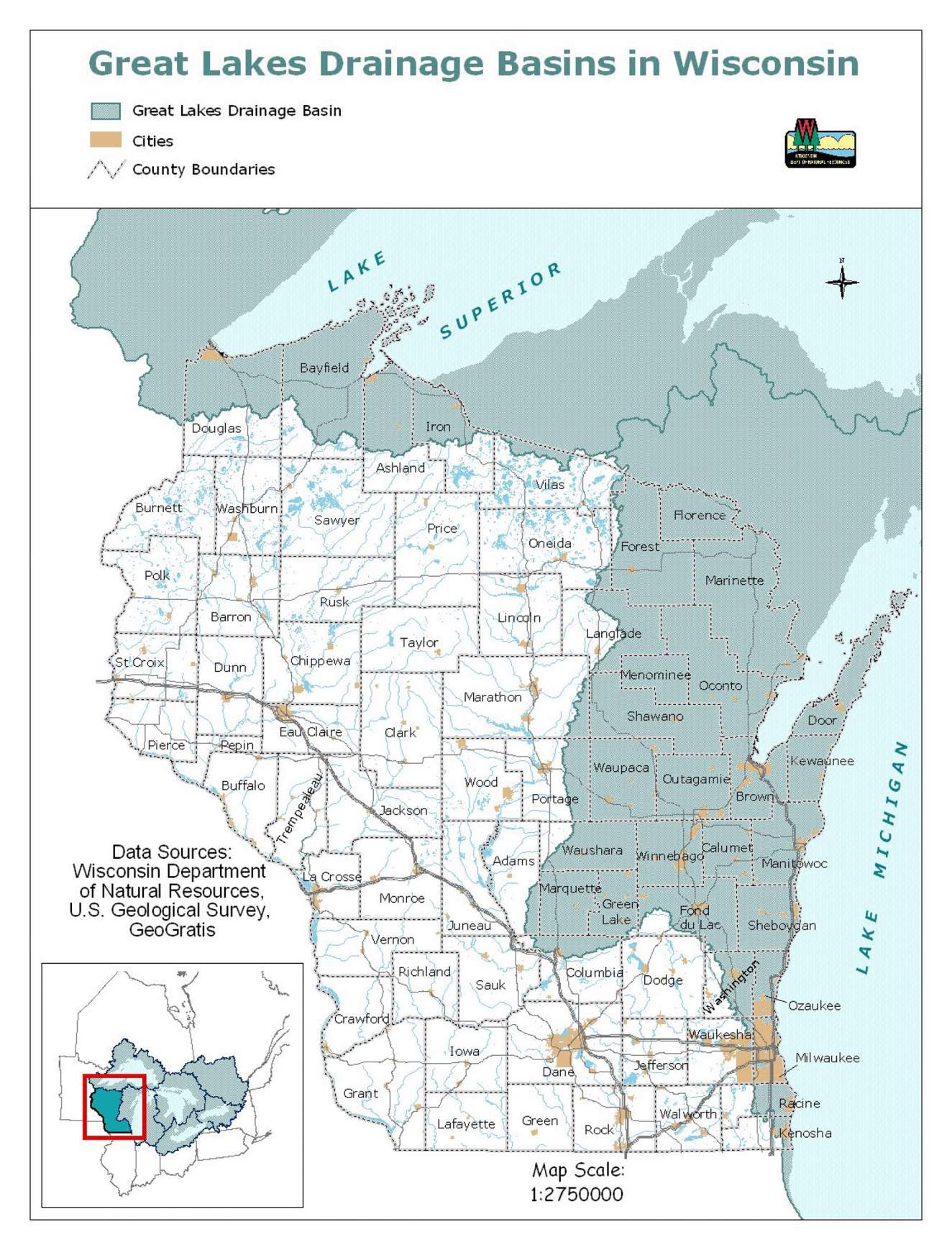

The Great Lakes Compact — an agreement among the eight U.S. states that border lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario — allows public water utilities to use water from these lakes if their municipalities fall completely or partially within the Great Lakes Basin, the drainage area in which surface waters flow into the lakes. Municipalities that are located within counties that straddle the basin's line, but are themselves wholly outside the basin itself, may apply for what's called a diversion. In 2016, the city of Waukesha became the first community to secure a diversion, which required the approval of the governors of all eight Great Lakes Compact states.

However, a private company like Foxconn would not be able to access Lake Michigan water directly. It will need to purchase it from a water utility that already has access. Given a planned location for the factory in Mount Pleasant, a village in southern Racine County, the company could work with one of several different utilities.

Communities within the Great Lakes Basin have some leeway as to where they can send their water in terms of the compact. Racine, Kenosha, Oak Creek and Milwaukee all pump water directly from Lake Michigan and sell some of it to smaller neighboring communities, a common practice on Wisconsin's Lake Michigan coastline.

Under the Great Lakes Compact, any utility with access to the lakes is allowed to pump a certain amount of water from them each day Most of the water these utilities withdraw eventually must be returned to the Great Lakes watershed in the form of treated wastewater. In the meantime, though, some of this water is technically allowed outside of the basin as long as an equivalent volume is returned later.

For instance, Racine can send water up to two miles west of Interstate 94, said Racine Water Utility manager Keith Haas. Some areas west of I-94 in Racine County are outside the Great Lakes Basin. But the Foxconn plant would not need to be located within Racine's city limits to buy water from the utility, Haas said.

In July 2017, then-Racine Mayor John Dickert told the Racine Journal Times that representatives from Foxconn had met with the city's water utility. In an interview with WisContext in September, Haas initially downplayed that report, but later said that he had indeed met with one engineer from the company.

However, so far no water utility has announced finalizing an agreement with Foxconn. Additionally, Haas said he's as much in the dark as anyone else when it comes to the manufacturing complex's eventual water needs.

Given a Mount Pleasant location, it's possible that Foxconn could try to source water from nearby Kenosha or Oak Creek, both of which draw water directly from Lake Michigan and serve water to other nearby communities. Oak Creek will be providing Waukesha with Lake Michigan water once the latter builds new infrastructure to connect up to the former's drinking water plant.

Individual states have some discretion as to how they enforce the Great Lakes Compact within their own borders. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources monitors and regulates all public water utilities in the state. Wisconsin's $3 billion incentives package for Foxconn includes several exemptions from environmental regulations, and relaxes some of the processes the state would otherwise use to enforce the compact in regards to the factory.

As Wisconsin's non-partisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau detailed in an analysis of the incentives bill, these changes would loosen the state's permitting requirements for water access if the Foxconn facility is located within a straddling municipality — again, that's a city, village or town that is partially in and partially out of the Great Lakes Basin.

If Foxconn didn't have a way to purchase water from a straddling community, it would either rely on groundwater or have to make its case to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Council, a regional body that enforces the compact.

Both cases are unlikely. If Foxconn chose to use groundwater, it would be drawing millions of gallons of water from sources on which farmers, businesses and residents in the Mount Pleasant area are already placing demands. Any proposal to do so would likely spark a controversy in its own right.

If Foxconn intends to use Great Lakes water, the company's calculations may have included choosing a site where its access to the water is subject only to state and local approval — within the Great Lakes Basin, or with close access to a water utility that's within it. A factory in Mount Pleasant, located to the east of I-94 and just west of the village of Sturtevant, fits that bill.

While Foxconn might not share many details with the public about its reasons for choosing the site in Wisconsin it did, it stands to reason that access to water and the rules of the Great Lakes Compact were major factors in that decision. The company selected a place where it can source water with relative ease — though there's some construction ahead to physically get it to the factory — and where the compact-related environmental exemptions in the state's incentives package will help it the most.

A Mount Pleasant location accomplishes Foxconn's water-related goals, while also placing a factory near transportation infrastructure and a populated region that can house employees. Had the company not chosen a site positioned strategically for water access, the process of accessing Lake Michigan water could take years and cost millions of dollars, as the experience of Waukesha has demonstrated. If Foxconn had positioned itself to go through such a process, it would be a strategic blunder for a company that's already secured state-funded incentives of historic scale. The promise of a $3 billion package was perhaps the manufacturer's biggest reason for coming to Wisconsin, but Lake Michigan's tremendous resources no doubt strengthened the attraction.