Hurricane Maria Accelerates Slow Drip Of Medical Supply Shortages

When Hurricane Maria struck the United States territory of Puerto Rico in late September 2017, it killed a still-undetermined number of people, knocked out power for most of the population, caused widespread flooding and created a humanitarian crisis that's still far from resolution. The effects reverberated far beyond the island, especially in the healthcare universe. Hospitals large and small across the continental U.S. including in Wisconsin, are dealing with shortages in the medical supplies and pharmaceuticals manufactured in Puerto Rico — the most troubled supply is that of IV bags.

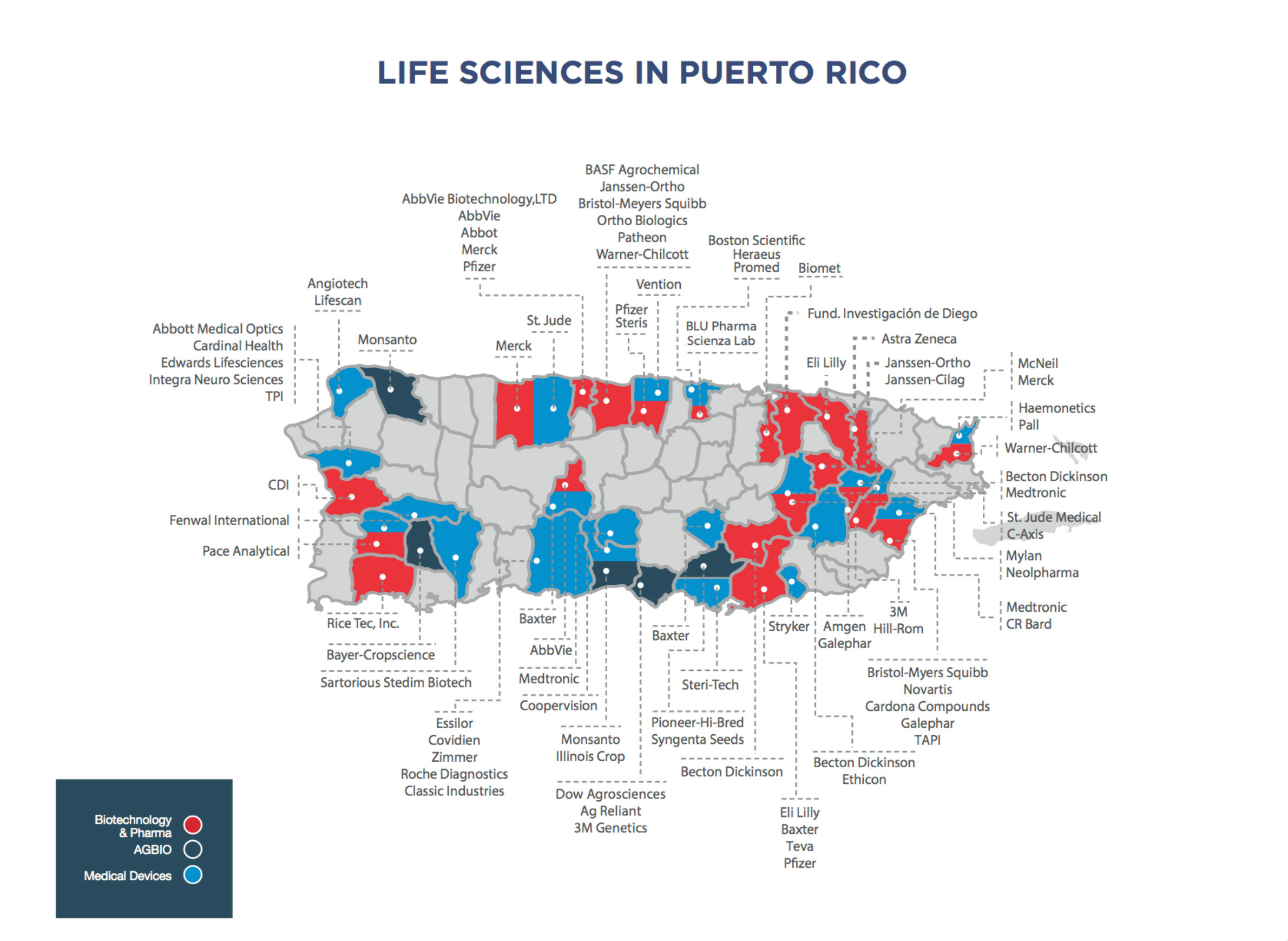

Over the past 40 years, Puerto Rico has lured manufacturers, especially pharmaceutical companies, with tax incentives to set up shop on the island. It's created a geographic concentration of companies that produce drugs, medical devices and additional supplies that hospitals and other health care providers rely on every day.

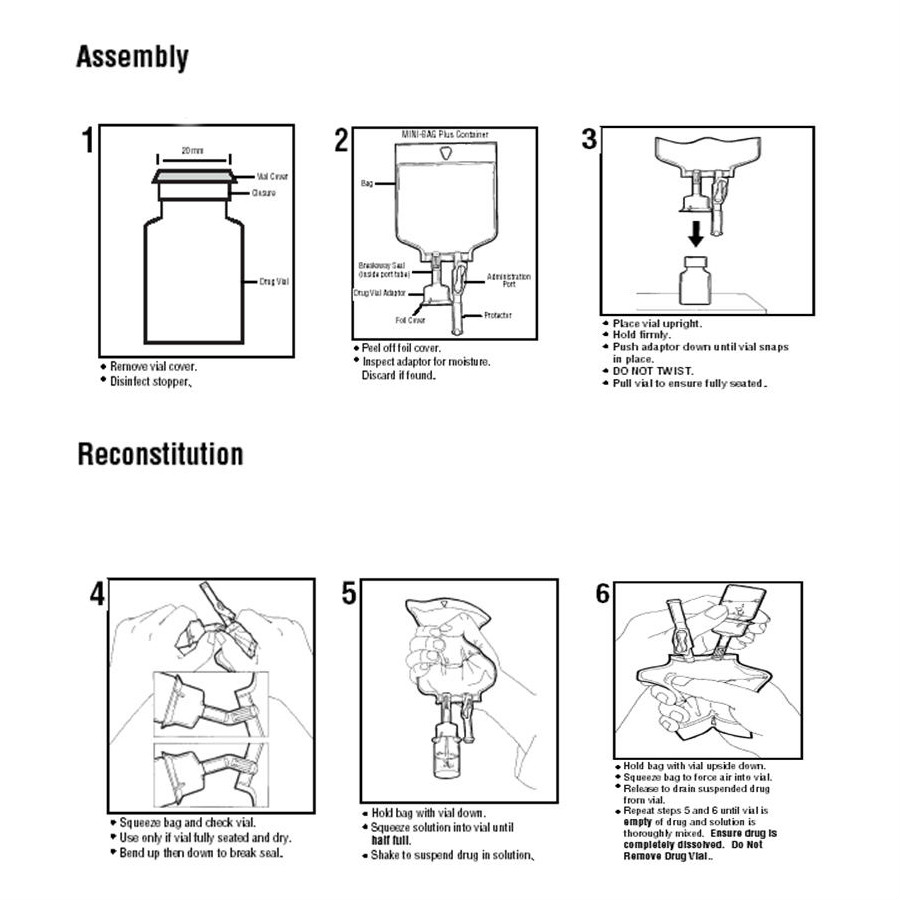

One of the most important medical products manufactured in Puerto Rico are IV solutions and pre-mixed drugs manufactured by Baxter International, a company based in the Chicago suburb of Deerfield. Healthcare providers across the continental U.S. have been scrambling to handle a shortage of assembled IV bags, among other materials, since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico.

Baxter's "mini-bags," as medical practitioners commonly call them, are filled with a saline or dextrose solution, and are used when a drug must be administered to a patient in diluted form over an extended period of time. If a hospital or other facility can't acquire enough of these mini-bags, it has to improvise other solutions. In turn, this supply challenge creates a chain reaction that can affect everything from the proper delivery of certain drugs to the way in which patient care is tracked.

The shortage has had an impact across the U.S. and around Wisconsin. At the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics campus in Madison, pharmacy staff have put in overtime hours to assemble mini-bags given the shortage of readily manufactured supplies.

Doing without IV bags isn't an option, or at least not a very practical one. Many drugs, from antibiotics to painkillers, need to be administered in a slow, diluted drip. Simply giving patients shots or pills isn't always a medically appropriate substitute, and it creates extra work for caregivers and other personnel to find an alternative solution. That approach in turn can strain a hospital's entire system of care and create extra costs. And more shots don't make patients any happier either.

"We could give you an injection in your buttocks or arm, but if you're getting an antibiotic four times a day, you're only going to tolerate that for so long," said Philip Trapskin, manager of patient care services at UW Health.

But these stopgap solutions have consequences at the local level. As hospitals scramble to acquire alternative materials in response to a shortage, their actions can create shortages in the supplies of those resources as well.

The vast majority of drugs and medical supplies used in the United States are manufactured domestically, which includes Puerto Rico, mostly because they need to meet Food and Drug Administration standards. The territory offers an extreme example of how a geographic concentration of medical manufacturers can become a vulnerable link in the supply chain.

Pharmacy purchasers deal with smaller disruptions in access to drugs and supplies every day, from FDA enforcement actions and drug recalls to market forces like price changes or a company deciding to stop making a given product. It's an ongoing challenge to adapt to these types of disruptions in a typical week. When an extraordinary event like a hurricane disrupts the supply chain to a greater degree, a variety of factors make it difficult for hospital pharmacies to adapt.

An opaque system

As the case of IV bags and Puerto Rico illustrates, one vulnerability in the healthcare supply chain is geographic in nature. A comprehensive view of this issue would assess where medical supply manufacturers are located, and determine which places might face threats, such as those related to from extreme weather or climate change-aggravated difficulties. However, not all pharmaceutical or medical-device companies actually divulge where their factories are located, and U.S. regulations don't require them to do so. Some companies make that information available to the public, but it's not all available to be be organized and analyzed.

"Even the FDA doesn't know where all these medications are manufactured across the country or the world," said Deborah Pasko, director of medication safety and quality at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. A professional organization for pharmacists, ASHP is also an attentive tracker of drug shortages. If both the FDA and ASHP struggle to anticipate drug shortages, that's a problem for the healthcare industry as a whole.

"To be high-reliability, you have to be proactive and you have to be able to predict and strategize around what may happen in the future," Pasko said. "But our pharmaceutical infrastructure isn't set up that way. It's meant to be, right now, a reactive thing."

One way to prevent, or at least anticipate, such shortages would be for pharmaceutical companies, healthcare providers and regulators to communicate to identify some of the most crucial drugs and supplies. With this knowledge, Pasko said, manufacturers could build redundancies into the system — making sure that multiple factories in different geographic locations are making a given drug, so that if one of them gets knocked out in a natural disaster or closed down in the wake of a drug-company merger, others can pick up the slack.

Right now, that type of communication doesn't exist. Pharmacy buyers can talk to each other about shortages they're encountering. Hospitals in the same geographic region or hospital system can coordinate with each other to make sure each is getting needed supplies. In the wake of Hurricane Maria, the FDA has been working with manufacturers and providers to temporarily increase imports of some necessary supplies.

The FDA's role doesn’t extend beyond that role, though.

"I think the FDA is very limited with the authority that they're granted to be able to make the status of the supply chain more transparent," said Philip Trapskin of UW Health. "So for instance if the FDA knows that there's 10 drugs on the island that are short or some key medical supplies that are short, my understanding is they're not allowed to disclose that publicly to the healthcare community, and there's nothing statutorily that requires drug manufacturers to disclose that either."

Shortages compound and spread

Andy Cohen, a clinical pharmacy specialist at the 250-bed Bellin Hospital in Green Bay, said he'd like the FDA to be more proactive and for the medical supply and pharmaceutical industries to offer more transparency in helping providers address drug shortages.

Even before Hurricane Maria, he said, shortages picked up considerably at the hospital over the past year, from one or two per week to several a day. Cohen has had to work harder to keep certain older kinds of injectable drugs in stock — he declined to specify which — because the FDA tightened regulations on some drug manufacturers in the wake of a 2012 meningitis outbreak caused by contaminated medications from a compounding pharmacy near Boston. Like many other hospital pharmacists, he's experienced a lot of anxiety over pre-filled IV bags since Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico.

"This is probably the most stretched in terms of resources that we've been ever, because as it compounds each day, it becomes worse and worse and worse in terms of the availability of fluid," Cohen said. "Through multidisciplinary approaches, we've been able to at least keep our head above water. However, you can only tread water for so long."

Meanwhile, different hospitals have different needs, different numbers of beds, different patient populations, different wholesalers and distributors providing their supplies, and of course, different budgets. It makes coordination in a crisis very difficult, and no one solution will make sense for all hospitals. This is one reason the Wisconsin Department of Health Services cites for not getting involved in the current shortage.

"We do not coordinate in situations like this, because different facilities address the situation in ways unique to their own plans and supply chains," said Elizabeth Goodsitt, a spokesperson for DHS.

But whatever their circumstances, just about every hospital in America will be touched by the IV bag shortage. Pasko said shortages of IV bags and other Puerto Rico-made supplies are causing problems at large hospitals and small clinics alike. The former will go through literally thousands of IV bags a day. The latter use less supplies overall, but often can't always afford to keep a backup of certain items in case they run out. Such is the case at 25-bed St. Mary's Hospital in Superior.

"In general, we don't get much warning of a shortage," said St. Mary's pharmacist Tonya Meinerding. "We usually find out when we go to order a product … we often don't know why it's on shortage or when it will be back in stock."

St. Mary's is part of a four-state system named Essentia Health, and Meinerding routinely coordinates with pharmacists at other hospitals in the network. If one hospital is short on a given item, often the others can help out.

"That used to be a once-a-week ordeal for me to deal with shortages … but [since Hurricane Maria] it's a daily concern," Meinerding said.

In addition to the now-ubiquitous struggles to keep IV bags in stock, St. Mary's Superior is also scrambling to source intravenous antibiotics and pain medications. So far, Meinerding said, the hospital has been able to find alternatives to deal with the shortages and maintain patient care, but even this exposes weaknesses in the supply chain. "It's just making the chain spread, because the manufacturers of the alternative were not prepared for shortages," she said.