The Murky Status Of Chronic Wasting Disease In Wisconsin

Chronic wasting disease used to frighten people in Wisconsin. The degenerative nervous-system disorder was first spotted in the state's white-tailed deer population around the turn of the century and has since become an established fact of life across much of the state. But between 2002, when the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources announced that CWD had been found in the state, and the 2017 gun deer hunting season, the issue has seemed to simultaneously escalate and fade into the background.

Over the years, DNR-led efforts to monitor and manage CWD have seen a dramatic decline in testing, and have yet to provide a clear picture of how prevalent the disease is overall. Yet even limited data points to a growing problem — as the state tests fewer deer over time, it finds more and more animals infected with this always fatal disease. At the same time, evidence is mounting that CWD, caused by infectious proteins called prions, could jump the species barrier to humans.

One journalist who's been following CWD since its arrival in the state, Ron Seely, discussed it on a Nov. 24, 2017 interview with Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now. Seely has reported for the Wisconsin State Journal and the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, and currently works as a freelance writer.

"I was working the beat at the State Journal then, and remember when the announcement was made and what a shock it was for the wildlife management community and for hunters," Seely said, recalling CWD's arrival in 2002. "I had families calling me asking whether they should eat the venison in their freezers."

That year and the three years following, the DNR tested tens of thousands of deer around the state. But in the past decade, testing has declined dramatically.

Gathering tissue samples from hunted deer largely relies on the voluntary efforts of hunters and taxidermists. Testing for CWD generally requires head and neck tissue that are tough to get from a live deer, and the hunting season is a good opportunity to gather many samples from around the state. Additionally, the DNR's capacities have been reduced by funding and staff cuts and political pressure. In 2016, the agency's wildlife health section chief told WisContext that the DNR didn't set a "hard goal" for the amount of samples gathered in recent gun deer seasons.

"There's been a tremendous downturn in the attention that we've paid to this," Seely said on Here & Now.

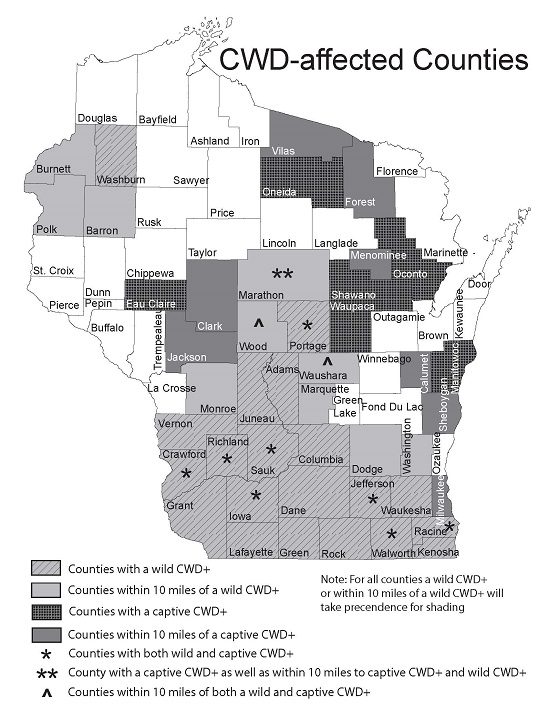

The geographic focus of CWD testing in Wisconsin is selective. From one year to the next, the DNR will rotate its tissue collection efforts to different areas of the state. The agency argues that this approach allows for a focus on CWD's spread within known hot spots, but it also means each year's numbers represent different sample sizes and geographic scopes. The only thing consistent about the data is that it shows the numbers — not percentages, but actual numbers — of CWD-positive deer in the state rising.

The trouble there is that without larger and more consistent data sets, wildlife managers and elected officials don't have a basis for crafting sound policy.

"The DNR isn't collecting enough data in a scientific way to allow it to make important management decisions," Seely said. "They have to reach a certain threshold in the number of tests they do, especially in areas where it's newly spread like Oconto County and Oneida County, and they're just not doing the number of tests they need to do in those areas." Seely added that scientists and researchers focusing on CWD are "very concerned about the lack of management response."

While CWD is a growing threat to the health of Wisconsin's deer population, scientists are still getting their heads around its potential danger to humans. Some prion diseases like Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (better known as mad cow disease) can afflict humans, though there is not yet scientific proof of a person acquiring chronic wasting disease. As Seely pointed out, there's still a lot people don't know about prions, how they spread and how they might jump a species barrier.

In July 2017, Canadian researchers published the results of a study in which cynomolgus macaque monkeys eating meat from CWD-positive deer became infected with the disease themselves. These results represent the first known instance of CWD jumping from cervids (the deer family) to primates.

Government agencies, including the state Department of Health Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, do warn people against eating meat from CWD-positive deer, which may be the best way to avoid prion exposure. Cooking meat thoroughly may kill most common pathogens, but prions are far more heat-resistant.

Venison and the meat of related species like elk isn't the only way prions can reach humans. These proteins can remain in soil for a long time and make their way into plants — deer may be able to pick it up from that source. In 2013, Seely reported on research that found prions could work their way into corn, tomatoes and other crops humans commonly eat.

Like Seely, scientists who study CWD are careful to point out that existing research does not conclusively point to the disease impacting humans. But the evidence is enough to keep observers on edge.

"It doesn't mean it's going to reach humans right away," Seely said, "but it means that that species barrier may be less of a protection than we thought."