What Made The Great Flu Pandemic Of 1918 So Momentous

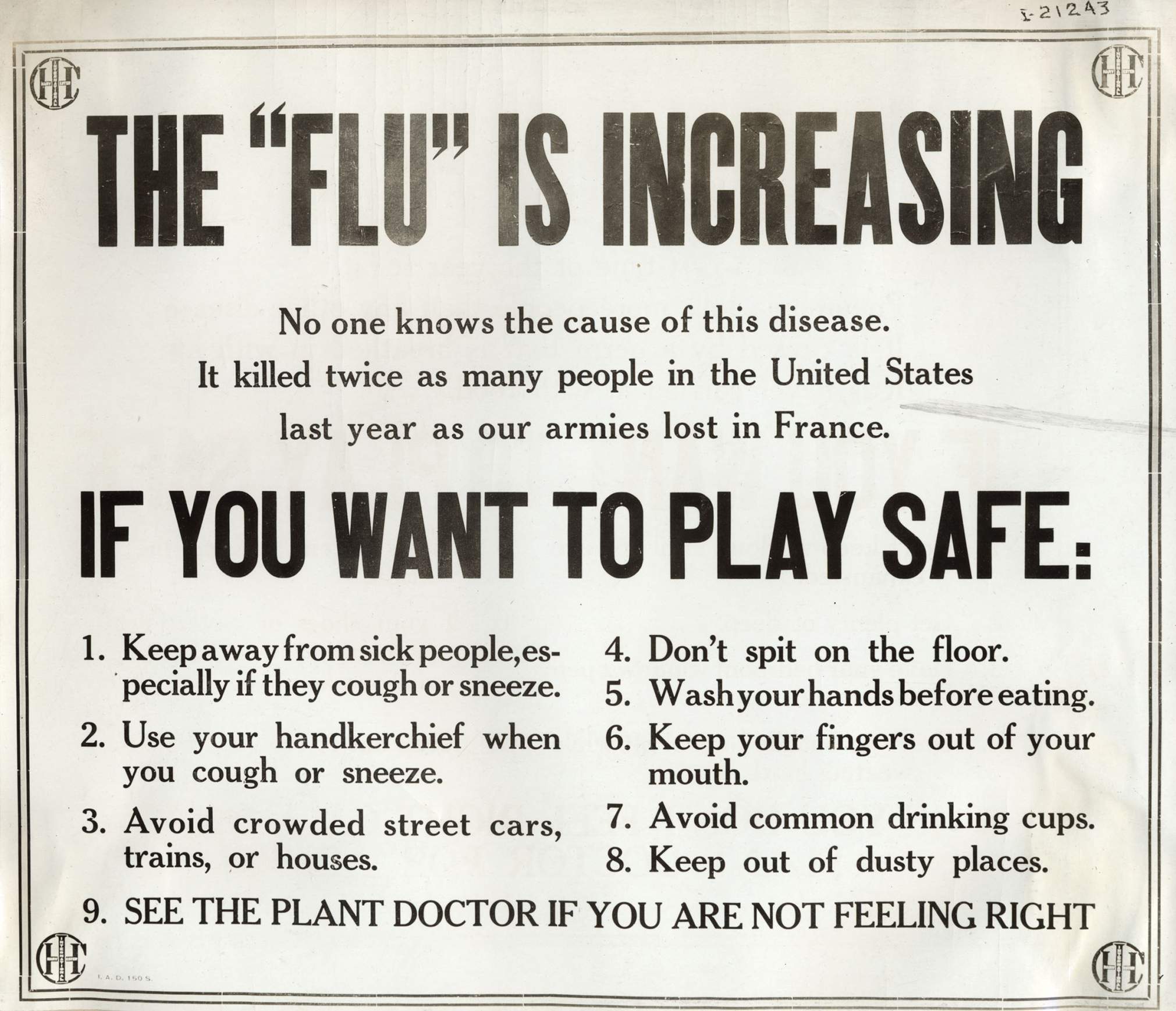

When a new and dangerous respiratory disease started racing around the globe in early 2020, it had been just over a century since humankind endured the 1918 influenza pandemic. While that wasn't the last time the world saw such a widespread outbreak — there were flu pandemics in 1957-58, 1968 and the 2009 H1N1 ordeal most recently — the scale of the World War I-era disaster looms large in both the history and science of communicable disease.

The emergent disease is called COVID-19, and caused by a novel coronavirus, a type of virus that includes those responsible for the SARS and MERS outbreaks in 2003 and 2012, respectively. To many people, it may seem hard to distinguish from the strains of seasonal influenza that hit in any given year. The illnesses share many symptoms, including cough, fever, sore throat — and pneumonia in serious cases. However, they're quite different.

While coronaviruses are a relatively recent discovery, first identified in humans in the 1960s, influenza as a malady has been observed by humans for more than 500 years. And while virology is a relatively new discipline, barely more than a century old, research into past influenza pandemics helps scientists understand how future outbreaks can impact society.

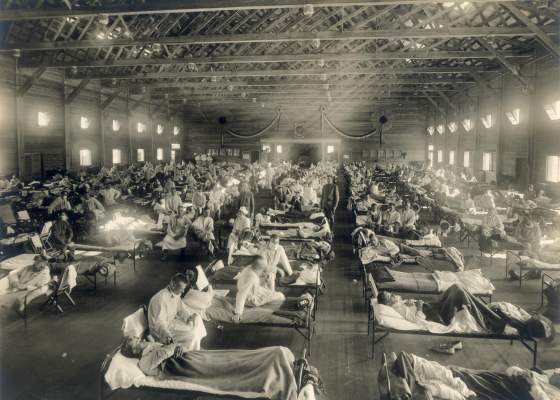

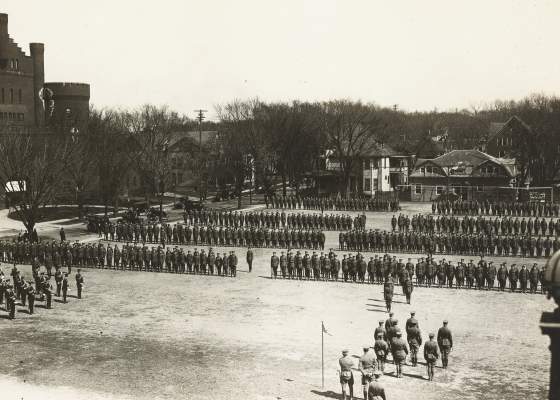

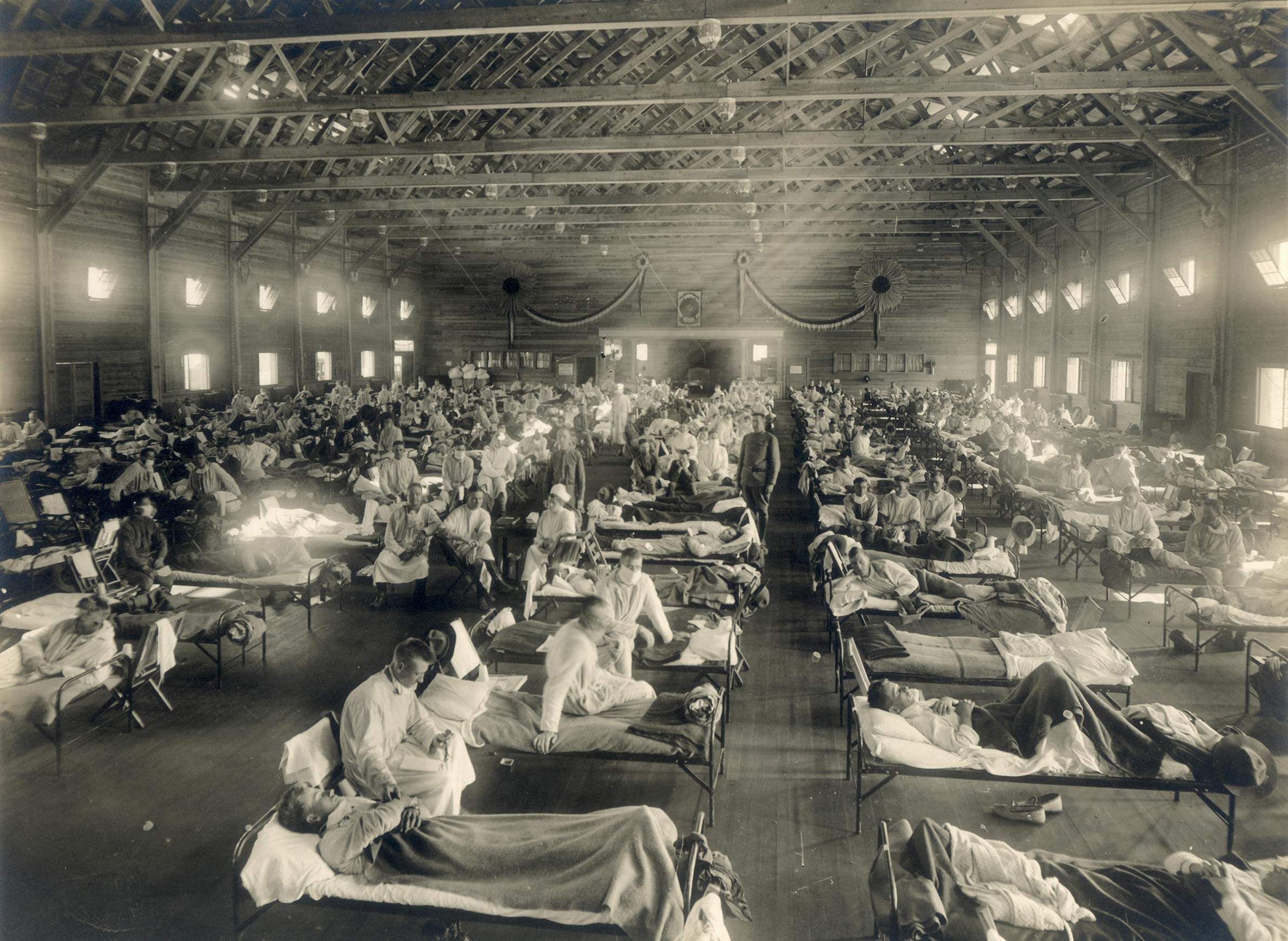

The worst and most notable flu outbreak in modern times is the 1918 influenza pandemic, responsible for millions of deaths worldwide. Peter Shult, director of the Communicable Disease Division at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, discussed the factors that contribute to pandemics during an Oct. 10, 2018 presentation at the Wednesday Nite @ the Lab lecture series on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus,and recorded for PBS Wisconsin's University Place.

"The great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 … ranks as one of the biggest and arguably most impactful of global health crises in human history," Shult said.

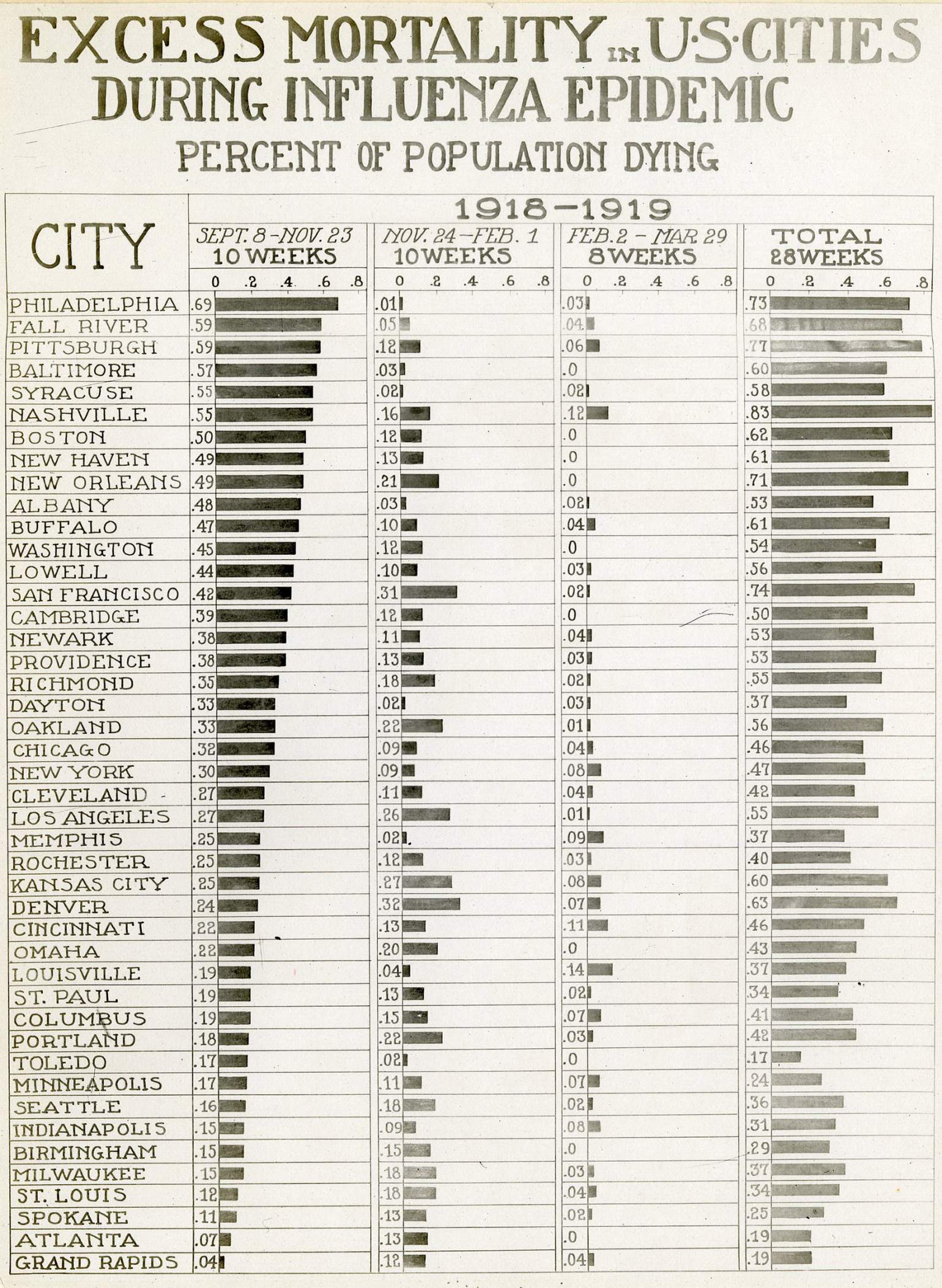

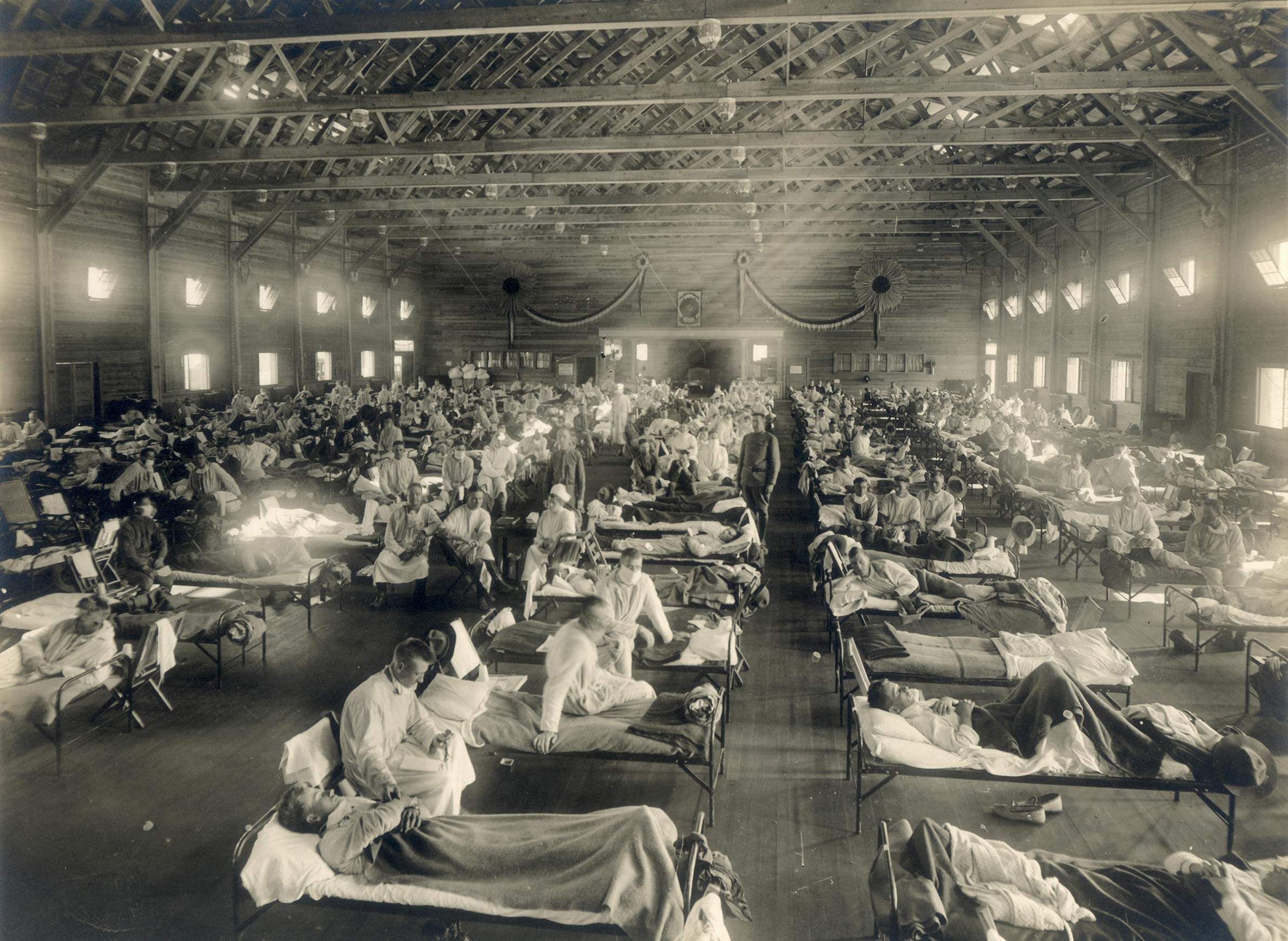

The 1918 influenza pandemic was unique in its significant mortality rates among otherwise healthy adults, whereas most fatal influenza cases typically appear among the very young or very old. Shult noted that pneumonia was a prevalent comorbidity during the pandemic, with around 15-20% of those infected developing a bacterial infection after the flu virus had weakened their respiratory system. All told, Shult said an estimated 50-100 million people perished in the pandemic.

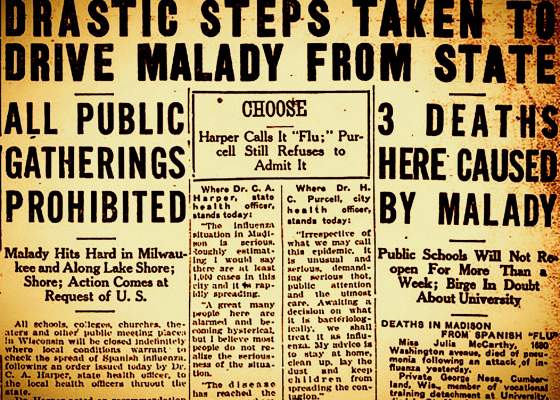

A pandemic is not defined solely by the pathogen; rather, Shult described a pandemic as the global outbreak of a disease that spreads rapidly and produces significant social and economic impacts.

Not every strain of influenza is capable of causing a pandemic; the virus is divided into sub-types A, B, C and D, with the first two having the most significant impact on human health. While both types A and B are associated with seasonal flu outbreaks, only type A has the potential to reach pandemic status. Flu viruses can change through what are called antigenic drift and antigenic shift, and it's this capacity that makes them more dangerous.

Influenza A is particularly well-suited to produce novel strains with high rates of transmission because its surface proteins, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, aid the virus's ability to latch onto and infect new cells. These are the H and the N that appear, respectively, in the taxonomy of flu strains, such as the 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic — the 1918 pandemic was likewise caused by an H1N1 virus. Influenza A also has an RNA-based genome, which allows it to frequently mutate, similar to the rapid changes that made HIV difficult to treat.

"The real hallmark of influenza is its changeability," Shult said. "One of the mechanisms leads to pandemic influenza. The other, much more subtle mechanism, leads to the seasonal epidemics that we experience each year."

Although pandemics impact a large portion of the world, seasonal strains of the flu can be more deadly. Thomas Haupt, influenza surveillance coordinator at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, discussed the yearly challenges posed by the seasonal flu in the 2018 lecture.

While the 2009 H1N1 outbreak was classified as a pandemic, the impact of the 2017-18 flu season in the United States surpassed it by almost every measure, Haupt said. Even without pandemic status, the 2017-18 seasonal flu sickened enough people to overwhelm hospital capacities in some areas.

The numbers of severe cases seen in 2017-18 lends perspective to the discussion around precautions taken to slow the rapid, pervasive spread of COVID-19.

"Almost a thousand people wound up in ICU [in 2018]," Haupt said. “Of that, like 273 people were required to get mechanical ventilation. Very serious year. Much higher numbers in every category. Broke every record. And not a record we wanted to break."

Key facts

- The 1918 influenza pandemic occurred in three distinct waves, with the second and third proving more devastating than the first. Its rates of mortality were exacerbated by secondary bacterial infections and worsened health that resulted from widespread and prolonged social breakdowns due to World War I.

- For several years after the 1918 influenza pandemic, the average life expectancy in the U.S. was reduced by 12 years.

- Migratory waterfowl are the primary host of influenza strains around the world. These birds carry all 16 hemagglutinin and all 9 neuraminidase proteins that can manifest in the influenza A sub-type, allowing the virus to rearrange itself into novel strains in a process known as antigenic shift. This ability can pose a threat to humans when birds carrying new strains come into contact with domestic poultry or other livestock and pass on different versions of the virus.

- Seasonal influenza is partially caused by what's called antigenic drift. It occurs as influenza viruses circulate around the globe and the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins acquire new mutations that enable various strains to stay a step ahead of hosts' immune response. These regular changes necessitate a new vaccine to be prepared every year, which can lead to inconsistent efficacy when the virus undergoes unpredictable mutations.

- Virologists monitor seasonal influenza outbreaks in the Southern Hemisphere to predict which strains will gain ground months later in the Northern Hemisphere and prepare appropriate vaccines. This approach is not always successful; the 2017-18 influenza season in the Southern Hemisphere was comparatively mild and did not accurately predict the record-breaking season that would follow to the north.

- FluView is an influenza monitoring tool produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It features weekly updates on current outbreaks, including influenza activity maps, information on prevalent strains and other relevant data.

Key quotes

- Shult on the impact of the 1918 influenza pandemic: "The case fatality rate was in excess of 2.5%. The worst pandemic since then and the worst season since then we're around 0.1%… During this period, it was estimated that a third of the entire global population, well over 500 million people, suffered clinical illness of varying degrees. And then there's been a lot of comparisons over time, comparing the impact of the pandemic and World War I."

- Shult on the 2017-18 flu season: "We heard of school closures, ERs and urgent care throughout the country being overrun. Hospitals had to divert patients because they couldn't take any more. There were shortages of medical supplies, saline, some antibiotics, antivirals, laboratory supplies in certain areas, particularly [those] associated with influenza diagnosis."

- Shult on the roles of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase: "The genes that govern those proteins are two of the most changeable genes in the virus. You can surmise this is a bad combination. The two key proteins that are most changeable are the ones we happen to mount our immune response to. Which means in short, our immune response, on a population basis, is always playing from behind. We're always a step behind, and that's what makes influenza such a very successful pathogen."

- Shult on the evolution of influenza: "It's well acknowledged that [the 1918 pandemic] was probably set off by an avian virus, but that virus was created because of reassortment going on in other avian species. That led to the [1918] H1N1 pandemic and that virus was with us for many decades until it combined with another avian virus. And the new virus picked up different components from that new avian virus and we ended up with the H2N2 virus, the cause of the Asian flu in 1957. A similar event occurred in 1968 when the H2N2 reassorted with another avian virus and we ended up with the H3N2; progeny of that H3N2 are the ones that are affecting us today... And finally, in 2009, H1N1 2009 arose."

- Haupt on the impact of the 2017-18 seasonal influenza season: "The next highest we had was 2014-15, where we had 4,700, so we practically doubled. What I have thought was going to be one of the worst years, 2014-15, that we had in decades — turns out [2017-18] really overshadowed that and made 2014-15 look pretty mild. But again, 66% of all of hospitalizations are people over 65 years old. Hospitals were overwhelmed. They did diverting ... there were a lot of hospitals that had absolutely no place to put people. It was a situation you would probably see in a pandemic, but again it wasn't as bad in 2009 when we actually did have the pandemic. But [2017-18] overpassed the 2009 [pandemic] in just about every single category."

- Haupt on influenza vaccines: "We never said it's been 100% — we try to explain what vaccine efficacy is: Some protection is always better than no protection. Think of yourself going outside in 10 below weather. You have a light jacket or something to go out and get your mail or do whatever you have to do outside, go to the car — it gives you a little bit of warmth. You won't freeze. It's like [the] same way with the vaccine."