When The 1918 Influenza Pandemic Struck Wisconsin

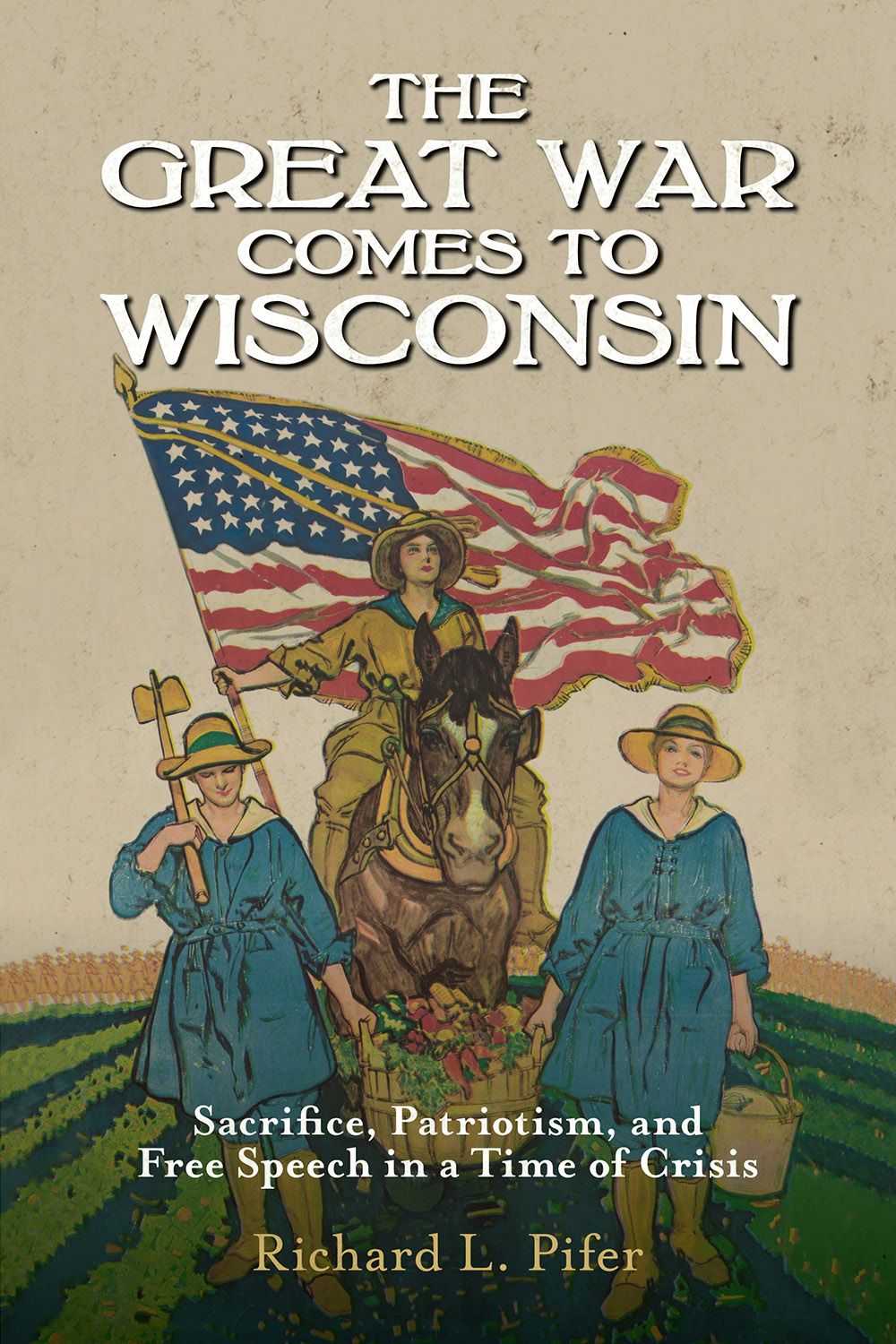

The entry of the United States into World War I in 1917 was a transformative moment in American history, as a national mobilization touched all aspects of society, redefining how people understood and practiced patriotism and civil liberties. The following year, as U.S. troops deployed to the Western Front in Europe and the war reached its battlefield conclusion, the emergence of the 1918 influenza pandemic underscored the enormity of the conflict and the changes it wrought. How this outbreak affected the homefront in the Badger State is explored in the 2017 book The Great War Comes to Wisconsin: Sacrifice, Patriotism, and Free Speech in a Time of Crisis, written by Richard L. Pifer and Marjorie Hannon Pifer, and published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. An excerpt from the book describes how Wisconsinites endured and responded to the pandemic, which was deadlier than the war itself in the U.S. and around the world. A century later, these experiences still resonate in efforts to understand influenza and prepare for future pandemics — a major public-health challenge in Wisconsin and across the nation.

As Americans entered combat in large numbers, news reports told of victories purchased at great human cost by the Allied armies. The news optimistically implied the war was being won, as communities mourned the deaths of their young men.

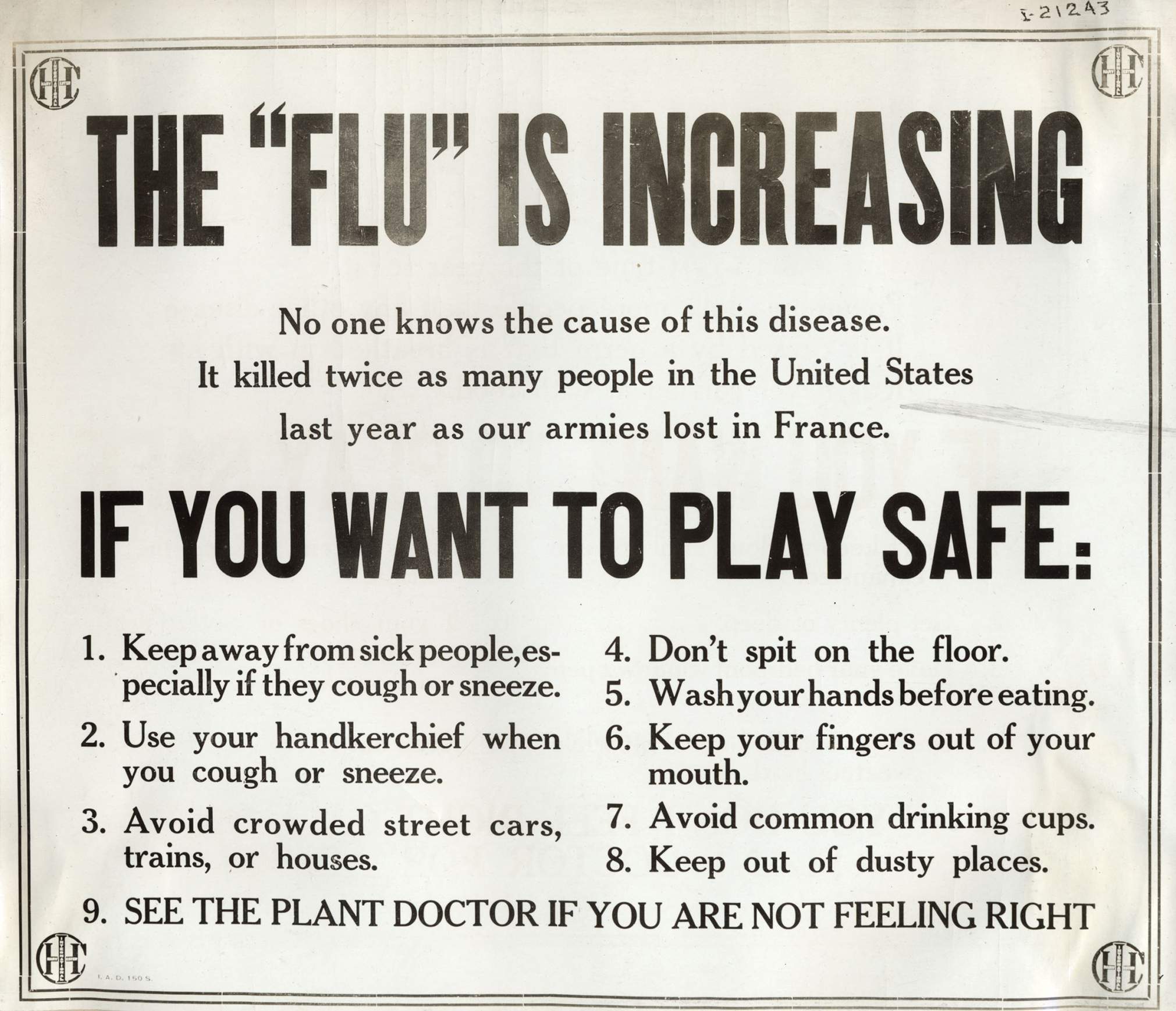

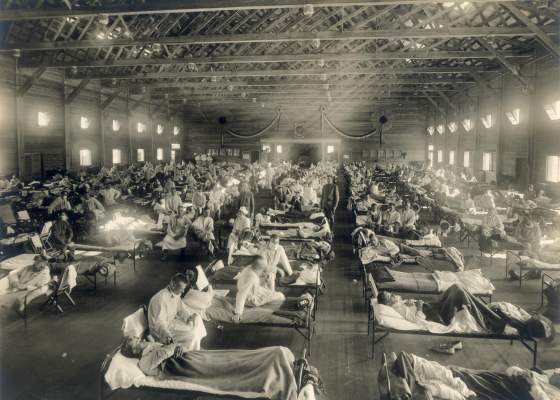

Other sobering news came from Europe as well. Soldiers were dying in large numbers not from battlefield wounds, but from illness. In addition to common ailments such as infection, dysentery, and pneumonia, newspapers began to carry stories of a lethal ailment sweeping through the armies of Europe in the summer of 1918. It was called the Spanish flu. It attacked young, otherwise healthy adults, killed quickly and often, and leapt from Europe to Wisconsin with unimaginable speed. Its cause was unknown; its mode of transmission was unknown; how to stop it was unknown.

The epidemic probably arrived in North America on a troop ship returning home. On September 14, 1918, doctors in Boston diagnosed the first case in the United States. Less than two weeks later the Spanish flu pandemic was wreaking havoc in Wisconsin. During the last five days of September, the number of new cases reported by health officials rose from 6 to 97. One week later, officials reported 256 new cases. Although no one knew it at the time, the epidemic crested on October 22 with a report of 588 new cases.

Midwestern states generally suffered fewer casualties from the Spanish flu than the more densely populated eastern states. Wisconsin was the only state in the nation to take aggressive and uniform action to limit spread of the epidemic.

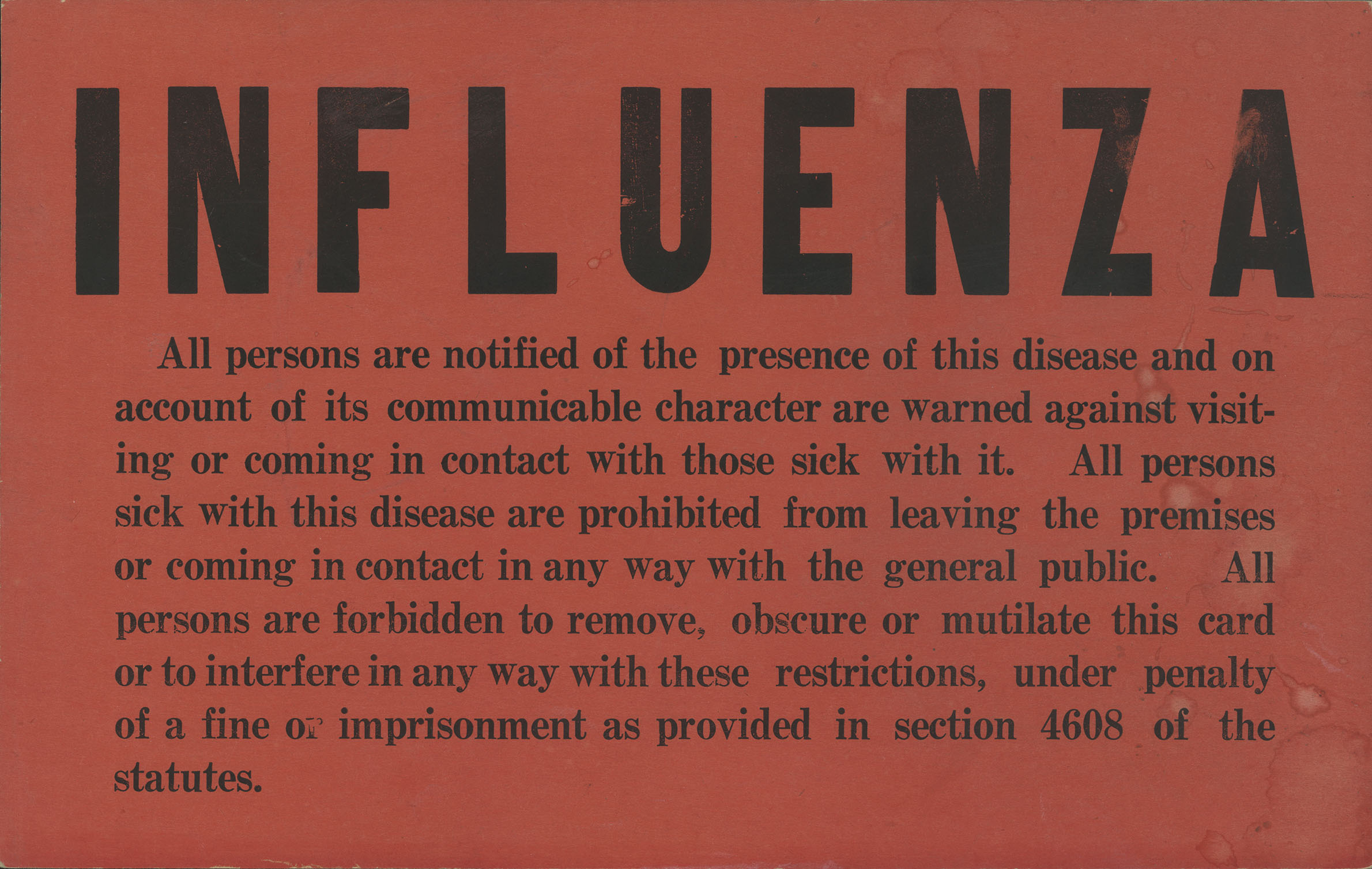

During a forty-year period the Wisconsin legislature had built the infrastructure for a modern public health system. In 1876 it created the State Board of Health with the power to issue statewide quarantine orders. In 1883 the legislature required every municipal unit to appoint local health boards and health officers. When the flu epidemic hit Wisconsin, the state had an existing public health framework within which to order and implement protective measures on a statewide basis.

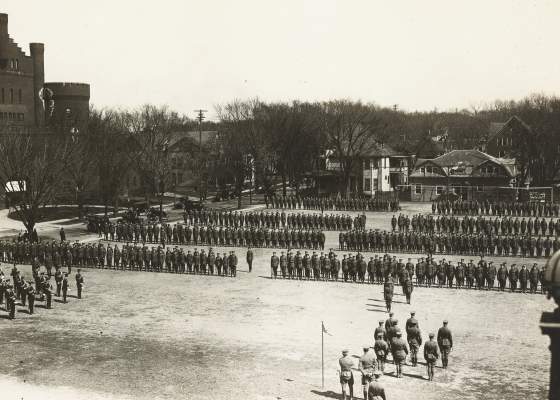

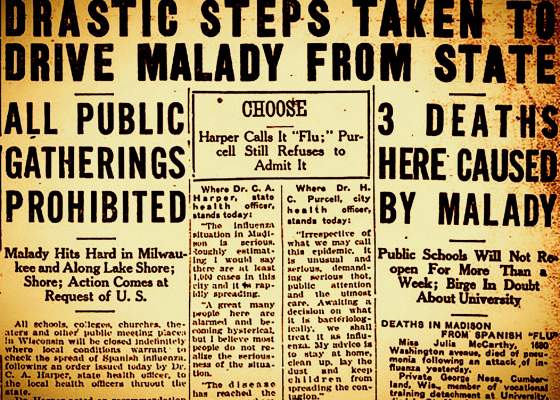

Without knowing how to stop the epidemic, Wisconsin took one of the few effective steps to curb transmission: it limited the places people congregated. On October 10, 1918, Cornelius Harper, the state health officer, consulted with Governor [Emanuel] Philipp and then issued an order instructing all local boards of health "to immediately close all schools, theaters, moving picture houses, other places of amusement and public gatherings for an indefinite period of time."

The order effectively closed every public establishment and gathering place, including churches, except for places of regular employment. In many communities, schools and theaters closed for four weeks and churches locked their doors for three weeks.

Nearly comprehensive statewide implementation took less than 24 hours. Failure to comply brought a swift response from Harper. For example, when Father J. M. Naughtin refused to close St. Rose Church in Racine, Harper called Archbishop Sebastian Messmer of Milwaukee, and the church quickly closed its doors.

Confusion over the nature of the order brought a tragic delay in Wausau. Although Harper intended his order to be mandatory, he also wished to give local officials latitude regarding how they implemented his instructions. He created confusion when he telegraphed the state's school boards: "Order issued as an advisory order. Local boards of health to use own judgment in closings."

Shortly thereafter, Harper received a call from Walter Heineman, one of Wausau's most prominent citizens, complaining that the local health board planned to keep the schools open another week. Through Heineman as an intermediary, Harper clearly instructed the board to close the schools immediately.

Heineman relayed these instructions to the mayor of Wausau by telephone, followed by a letter to the mayor in which he claimed Wausau was the only city out of compliance with the closure order, that the board risked an order quarantining the entire city, and that failure to comply "would lay any community open to criticism as being pro-German." For good measure, he also sent the letter to the Wausau Daily Herald for publication. Heineman's slight to their patriotism angered members of the local board of health. Harper was working to clear things up when the epidemic hit Wausau and made the board's course clear.

Unfortunately, the misunderstanding gave students and teachers an extra week to spread the contagion, and Wausau officials found themselves fighting one of the worst outbreaks in the state. Nonetheless, effective cooperation between the Board of Health, the county Council of Defense, state officials, and a small army of volunteers limited the death toll and placed Marathon County in the lowest death rate category with only 0 to 20 deaths per 10,000 people.

For reasons still unclear, Ashland, Iron, and Kenosha Counties suffered the most severe epidemics and experienced death rates of 50 to 60 deaths per 10,000 people. In contrast — probably a result of advanced public health practices at the time — Milwaukee's tightly packed population experienced only 20 to 30 deaths per 10,000 people.

The state's prompt response to the epidemic and the willingness of residents to abide stringent restrictions limited the spread of the disease. This cooperative spirit mirrored the ways in which they were conserving food, buying bonds, and volunteering for war work.

Though new cases would continue to resurface and confound health officials, the epidemic was in decline by the end of December. In total the Spanish flu afflicted an estimated 103,000 Wisconsinites and killed 8,459, either from the flu itself or from related pneumonia. In the end, the Spanish flu epidemic killed more than four times the number of Wisconsin residents than did the fighting on the western front.

Sources:

- Green Bay Press Gazette, October 31, 1918, 2.

- Steven Burg, "Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918," Wisconsin Magazine of History, 84, no 1 (Autumn 2000), 36–56.

This item was excerpted from The Great War Comes to Wisconsin: Sacrifice, Patriotism, and Free Speech in a Time of Crisis, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press. Author Richard L. Pifer retired in 2015 from his position as director of reference and public services for the Library-Archives Division of the Wisconsin Historical Society. He received a PhD in American history from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His historical research has focused on the history of the home front in Wisconsin during the First and Second World Wars. Dr. Pifer is also the author of City at War: Milwaukee Labor During World War II. Contributing author Marjorie Hannon Pifer worked for twenty-six years as a health care program and policy analyst for Wisconsin's Department of Health Services, until her retirement in 2015. She holds a master's degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her career prepared her well for the role of historical analyst.

This report is the copyright © of its original publisher. It is reproduced with permission by WisContext, a service of PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio.