A Fierce Hurricane Season Hones Tracking Research At UW

From Harvey to Irma to Maria, there have been no shortage of catastrophic hurricanes leaving parts of the U.S. and its territories under water and their residents on edge. But the technologies that track these storms is improving, and scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are helping lead the way in the field.

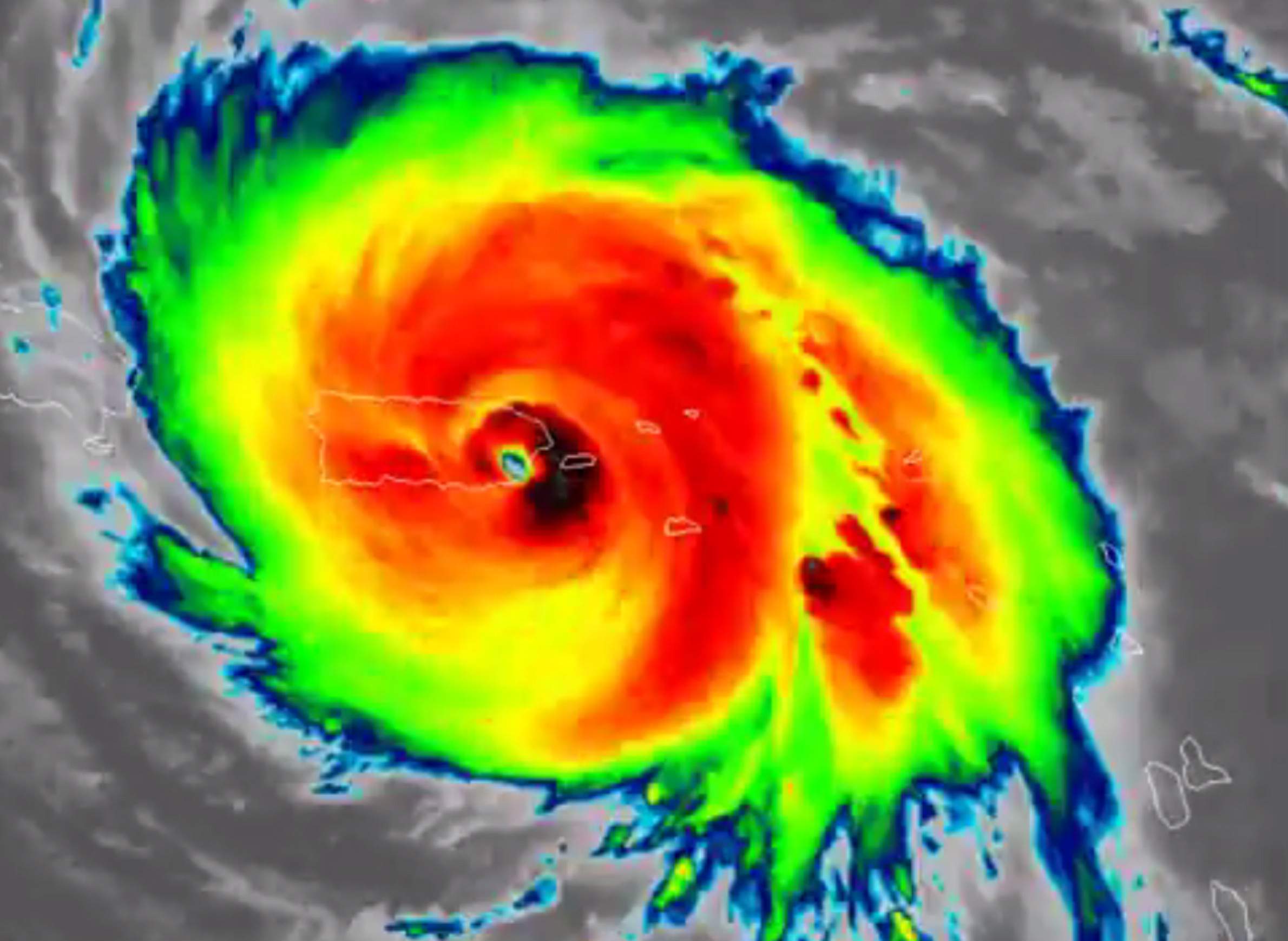

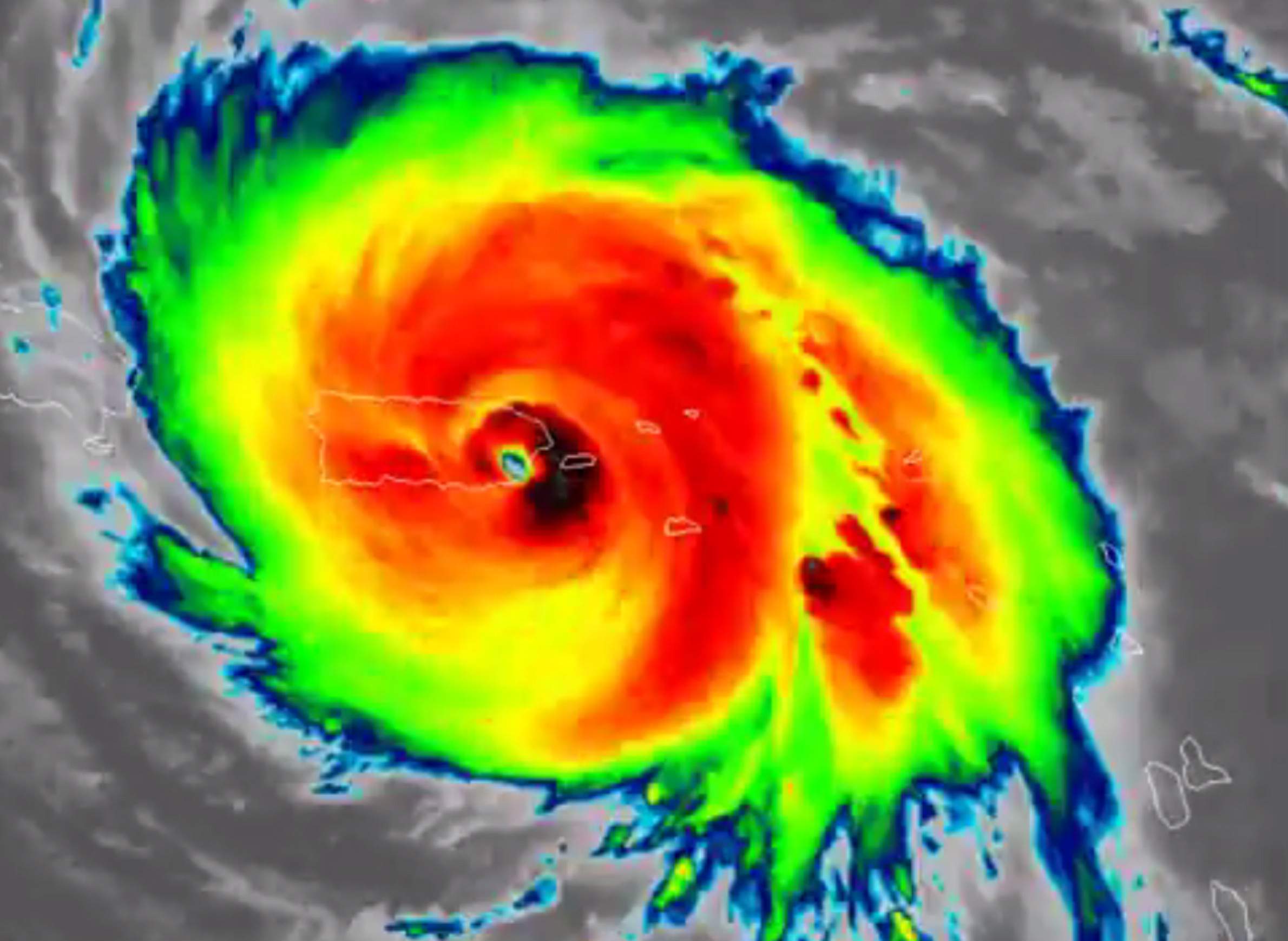

Most recently, the Tropical Cyclone Research group at UW-Madison's Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies tracked the movement of Hurricane Maria, which ripped through Puerto Rico in late September as a Category 4 storm, leaving the entire island without power.

Derrick Herndon, a researcher with the Tropical Cyclone Research group, said that despite the seemingly endless series of intense storms over the summer of 2017, the hurricane season is not an unusual one.

"We could go back to 2005, which wasn't that long ago to a season where we have five category 4 or stronger storms," he said in a Sept. 22, 2017 interview with Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now.

The 2017 hurricane season, while not unusual, has been a record setter. Herndon said Hurricane Irma set the record for the strongest hurricane ever in parts of the Atlantic Ocean it struck. He attributed this and the intensity of other storms to warmer ocean waters.

Herndon said while meteorologists have made big strides in forecasting where hurricanes will strike, predicting their intensity is a different story.

Predicting hurricane intensity continues to be a tough hurdle for scientists to overcome, and Herndon said the rapid intensification of storms is one of the biggest concerns for climate researchers. Fox example, Hurricane Harvey intensified from a tropical storm to a Category 4 hurricane in 36 hours.

"When you consider we're going to issue a hurricane watch 48 hours out, that gives us very, very little time to evacuate the coastal communities," he said.

While there is still much progress to be made in forecasting storms, scientists have made big strides in the field, said Jonathan Martin, a UW-Madison professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, in an August 2015 interview with Wisconsin Public Radio's The Larry Meiller Show. He said the most severe hurricanes that the U.S. experienced in much of the 20th century were some of the most deadly simply because they struck without warning.

"It’s like another world compared to what it was even 25 years ago," Martin said.

Speaking to Here & Now, Herndon noted scientists have been able to cut their forecasting track errors in half over the past 15 years. But he said some of this progress is offset by growing populations in areas prone to hurricanes and the fact that cities need longer lead times to evacuate.

Just as technology to track hurricanes has advanced over the years, so has the technology to predict major flooding. And with the amount of water Hurricane Harvey poured into Texas, the study of precipitation and floods has become all the more important.

Shane Hubbard, a postdoctoral researcher with the UW-Madison's Space Science and Engineering Center, said scientists have also known for a long time that major floods are becoming more common. The U.S. saw an increase in heavy rainfall between 1958 and 2012, with the largest spikes occurring in the Northeast and Midwest, he said.

"We know that flooding is changing, people can feel that," Hubbard said in a January 2017 talk at UW-Madison. "Seems like you turn on the TV anywhere from February through July, and every week, once a week you're seeing a community that's fighting floods."

Herndon echoed this sentiment and said when a series of strong storms occurs, people can get what he called "hurricane fatigue." When the hits keep coming, he said, it can be hard to move resources adequately and give people the help they may need.

"I know a lot of people in Texas were concerned that their story was basically being lost because it was followed very quickly by Irma, which was a deadly hurricane and damaging hurricane in Florida," he said. "So it can be very difficult in terms of moving resources to the right places because we have so many storms making landfall and impacting land and people's lives."