Navigating The Confusion Of Wisconsin's Voter Roll Purge

Wisconsin's growing mosaic of struggles over voting rights grew even more complex in March 2018, when Milwaukee officials raised questions about a program that deactivated around 44,000 voter registrations in the city. This election-related concerns materialized the same week a Dane County judge ordered Gov. Scott Walker to hold special elections in two vacant state legislative seats, in a ruling that referenced the pending and potentially historic U.S. Supreme Court case over gerrymandering in Wisconsin. Amid these battles, the way Wisconsin goes about maintaining and pruning its voter rolls may become another focus of debate.

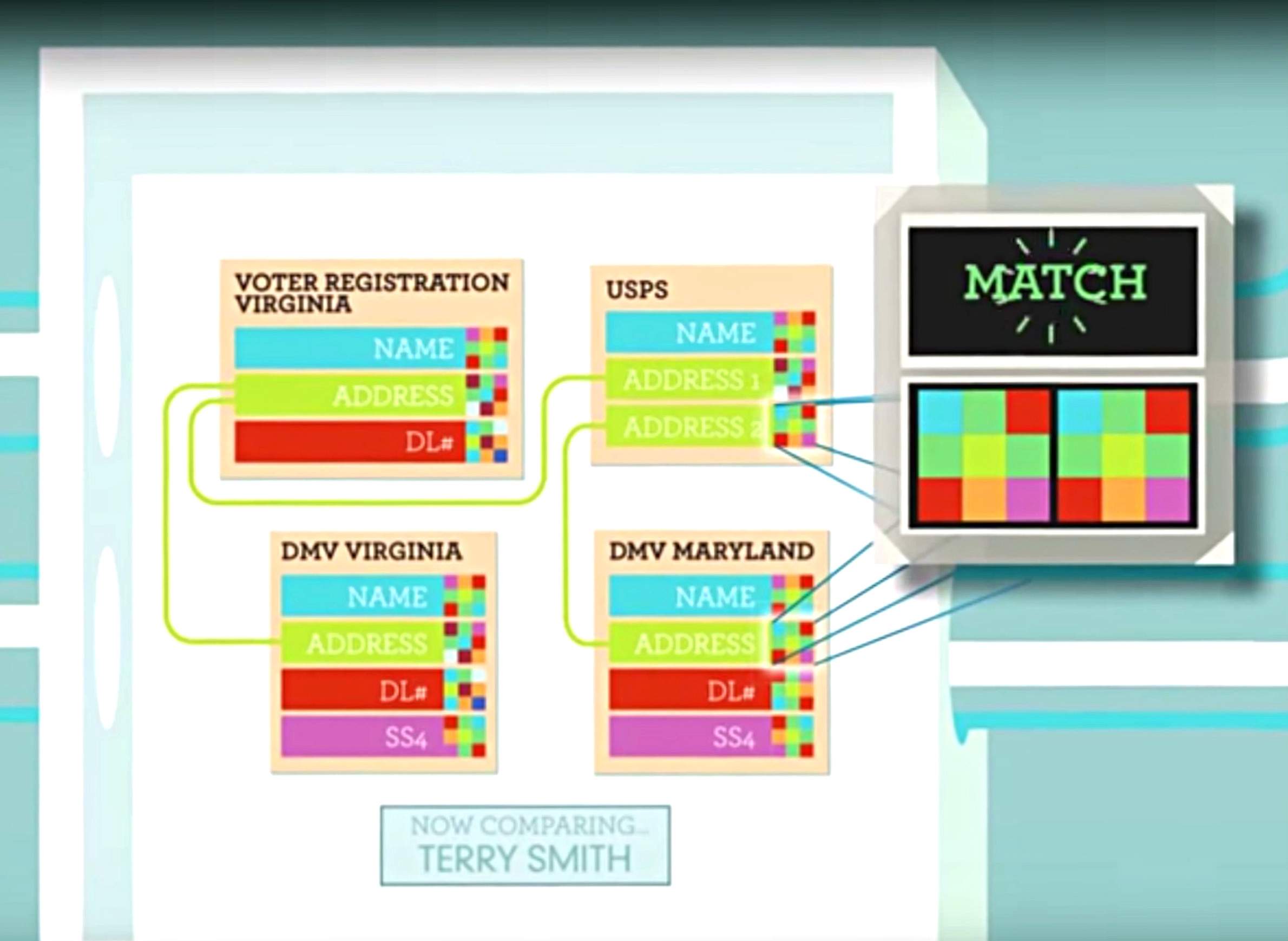

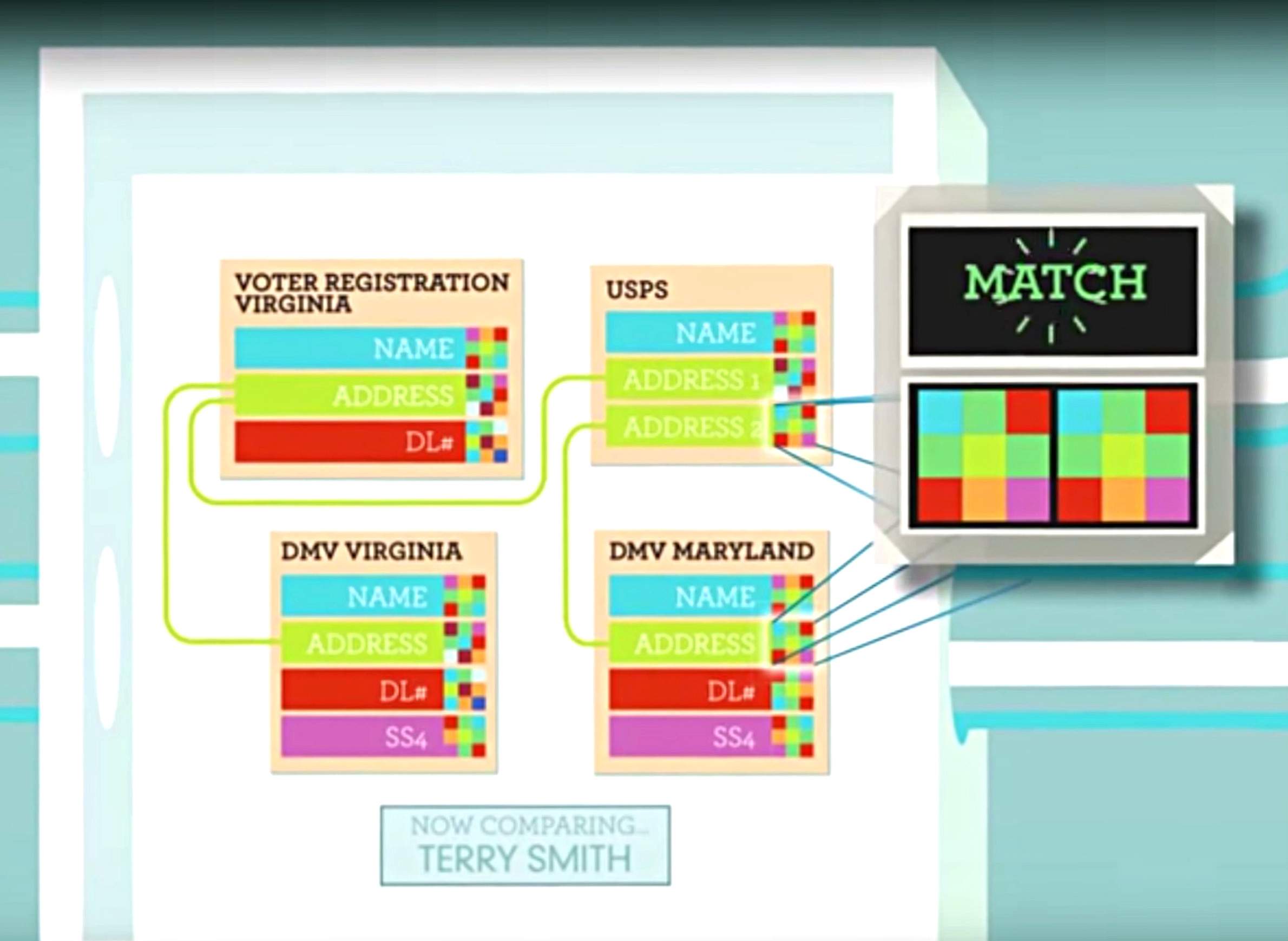

In 2016, the state of Wisconsin joined an organization called the Electronic Registration Information Center, known as ERIC. The nonprofit organization has 23 member states as of March 2018, and describes its goals as "assisting states to improve the accuracy of America's voter rolls and increase access to voter registration for all eligible citizens." Through ERIC, states share data and technical tools in an attempt to check the accuracy of their voting registrations — the group explains its approach in an introductory video.

In November 2017, the Wisconsin Elections Commission sent about 343,000 postcards to registered voters who were thought to have possibly changed addresses. Through an ERIC-facilitated process, the Commission deactivated about 308,000 voter registrations in the state of those recipients who didn't respond, including those in Milwaukee.

In a March 23, 2018 interview with Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now, Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett discussed the deactivations, raised concerns about the possibility of erroneous purges and explained what the city is doing about the issue. He repeatedly emphasized that he wasn't accusing ERIC or the state of doing anything inappropriate with the city's voter rolls, summing up the issue as "the computers didn't talk well to each other."

Barrett said that ERIC, in voiding registrations it flagged as having outdated addresses, likely swept up people whose registrations were in fact current but had older addresses listed in other databases the group uses, including from the state Department of Transportation and the United States Postal Service. He also admitted that the city wasn't actually sure how many Milwaukee voters might have had their registrations deactivated in error.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission has said that it reactivated about 7,000 ERIC-voided registrations statewide after the February 2018 primary elections, acknowledging those were voided in error and created difficulties for some voters whose registrations were accurate. Commission spokesperson Reid Magney discussed those issues, and offered some more background on the state's voter-roll maintenance processes, in a Feb. 23 interview with Here & Now.

"Sometimes the DMV has information based on their address one way and we might have it in the voter records another way," Magney told Here & Now, discussing registration issues that emerged during the primary. "This is the first time we've done this kind of a match. And so I think we're learning from it."

Barrett, a Democrat who has lost two gubernatorial elections to current Republican Gov. Scott Walker, did criticize the state for what he saw as a hasty rollout of its new voter-roll cleanup program. Since its introduction, both state and Milwaukee officials have made efforts to reach out to purged voters and alert them to renew their voter registrations.

"We believe that this is not ready for primetime," Barrett said to Here & Now. "In order for this system to be put in place, you want to make sure that you are not taking people's names off the voting rolls if they're eligible to vote. The constitutional right to vote should be paramount here."

One reason why these voter registration deactivations are so fraught is that there are active political battles at both the state and national levels over policies that can limit access to the polls, especially in urban and rural areas, and among minorities, the elderly and college students.

Republican legislators and governors in many states have passed voter-ID laws, including in Wisconsin, with its fate still playing out in federal court. A University of Wisconsin-Madison study found that the state's law may have prevented thousands of people from voting in the November 2016 election. At the beginning of 2018, state transportation officials consolidated driver's license service centers on the west side of Madison, which will demonstrably hinder people who depend on public transit in getting or renewing state-issued IDs. Additionally, opponents of voter-ID laws have pointed out that eligible voters in multiple states have a hard time accessing DMV locations.

At the national level, Wisconsin elections officials in summer 2017 responded cautiously to a sweeping voter-data request from a since-disbanded White House panel founded on unsubstantiated claims of widespread voter-impersonation fraud.

The state will put voters voided by ERIC on a supplemental poll list, separate from the main list of valid voter registrations poll workers use.

Barrett sees it as a short-term fix and doesn't know how well it will work in the upcoming spring election, or whether it will be used in the fall election.

"If you're not on the first list, you don't know necessarily that you're on the second [supplemental] list," he said.

Of course, ideally local and state elections officials, and poll workers on the ground on Election Day, can help voters navigate such confusion. Milwaukee officials are undertaking some additional training for poll workers in the city so they can help voters who might be on the supplemental list. However, Barrett pointed out that this approach will cause delays as people line up to vote, and couldn't promise that people won't fall through the cracks.

"If you know enough to go to the second list, you might be on the second list," Barrett said. "That assumes two things. It assumes, one, the poll worker knows to go to that second list, and we're going to try to make sure that happens. I can't guarantee that 100 percent of the time — or that you know there's a second list you should be checking."