A Series Of Unprecedented Events

A span of 83 days elapsed between Dec. 29, 2017, when two Wisconsin state legislators resigned their positions to take jobs in Gov. Scott Walker's administration, and March 22, 2018, when a circuit court judge ordered the governor to call special elections for those seats within a week. On March 29, when Walker ordered elections be held, that span reached an even 90 days. It was three months in which a seemingly mundane state personnel matter snowballed into a string of inaction and action across all three branches of government that was unprecedented in Wisconsin's political landscape.

Special elections are an irregular yet customary feature in state-level politics, held after a seat is vacated by an officeholder at local, state and federal levels. Vacancies can arise in a variety of offices for a variety of reasons, and are fairly common in the state Legislature. In Wisconsin politics over the past half-century, there has been at least one state legislature vacancy in a majority of years, though they can be far more frequent too, with as many as a half-dozen arising as officeholders resign or die.

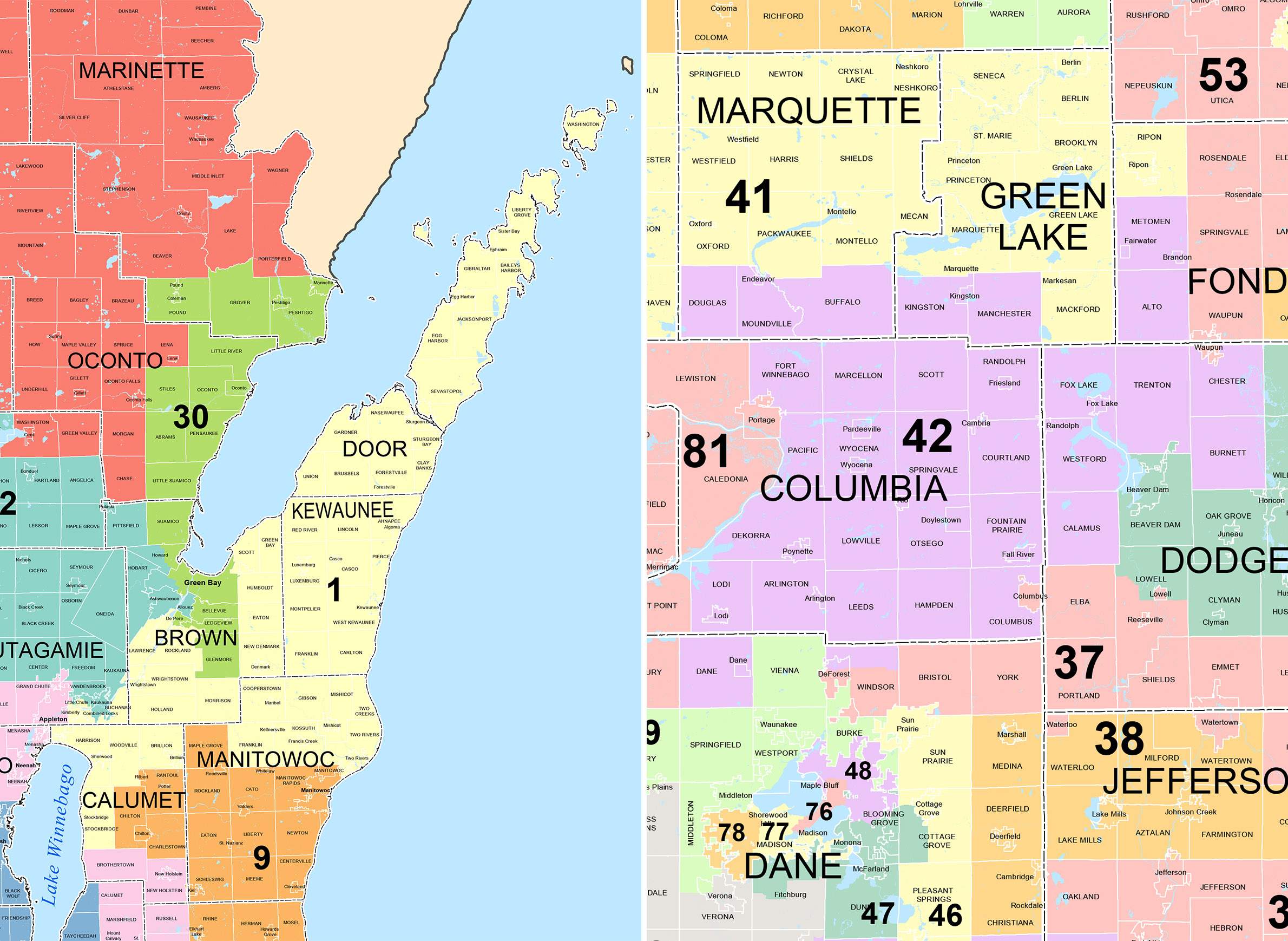

In the case of the two state legislative vacancies that sparked a court order, the specifics are simple, even banal. Frank Lasee and Keith Ripp, Republican legislators who represented Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 respectively, resigned their seats to take positions at state agencies. In short, they were hired by the Walker administration, and instances when governors create vacancies via human resources moves are fairly common. What followed, though, was not.

The Lasee and Ripp resignations were announced on Dec. 29, 2017 and took effect on the same day. At the same time, Walker signaled that he would not call special elections for the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats, meaning that voters would not get a chance to select their representatives until the Nov. 6, 2018 election, and those seats would remain unfilled until January 2019. Altogether, it would have meant each district would go unrepresented for more than a year, an unprecedented length of time in modern Wisconsin politics.

While the specific circumstances of legislative vacancies can be humdrum or unique, the time frame in which such seats have been filled has been fairly consistent. Between 1971 and early 2018, more than 100 legislative vacancies in Wisconsin have been filled by special elections held within 2 to 4 months. Nearly another 50 vacancies were not filled in such elections. However, no vacancy researched in an extensive WisContext investigation of state records lasted as long as a year.

These vacancies would have been unprecedented for Walker himself. The governor had previously called special elections for 14 open seats, with the time between vacancy and voting not exceeding 121 days in any instance.

Walker ordered the special elections for the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats to be held on June 12, 2018, with any necessary primaries to be held on May 15. Altogether, a span of 165 days will have passed between when the resignations were formally announced and elections are held.

What Wisconsin's special-elections law means

It was 59 days between the Lasee and Ripp resignations and the Monday when eight Wisconsin voters challenged Walker’s decision. On Feb. 26, 2018, these plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against the governor in Dane County Circuit Court seeking what's called an order of mandamus that would require the governor to call special elections for the two open seats.

This case addressing the two legislative vacancies, Newton v. Walker, is unprecedented in modern Wisconsin politics, in that there has not been a previous instance in the state of voters filing a lawsuit against a governor in order to compel them to call a special election. Likewise unprecedented in legal terms is previous jurisprudence and federal law addressing this type of issue. While there have been multiple cases of lawsuits filed in other states over governors refusing to call special elections, their applicability to Wisconsin is very limited.

The argument made by the plaintiffs in Newton v. Walker was simple: the language of Wisconsin law plainly defines the governor's responsibilities to call special elections and Walker is violating it. The argument made by the defense, represented by Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel and Wisconsin Department of Justice lawyers, likewise focused on the wording of state statue, but interpreted its requirements quite differently.

It all boiled down to statue section 8.50: "Any vacancy in the office of state senator or representative to the assembly occurring before the 2nd Tuesday in May in the year in which a regular election is held to fill that seat shall be filled as promptly as possible by special election."

The plaintiffs' lawyers argued that the vacancies announced on Dec. 29, 2017 are covered by this requirement, while the defendant’s contended that "in the year in which a regular election is held" only speaks to those openings that arise in even-numbered years. Therefore, by this rationale, if the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats were vacated between 3 and 130 days later (on May 8, 2018, the month's second Tuesday), Walker and Schimel conceded that the governor would have been obligated to call special elections.

Dane County Circuit Court Judge Josann Reynolds, who heard arguments on March 22, promptly issued an oral ruling that same day. She rejected Walker's and Schimel's interpretation of the law, saying it "was absurd in its application."

Citing the language of the statute, Reynolds ordered the governor to call special elections "as promptly as possible" [emphasis in original] in the vacant districts and no later than noon on March 29. She declared the governor has a "plain and positive duty" to do so and that the plaintiffs "possess a clear legal right" to such an action. The judge ordered that special elections should be held between 62 and 77 days after being called by the governor, which is the same period of time required by state law.

"Is the view that the role of legislator is so insignificant that we don't need one for a year?" asked Alvin Mayer, a plaintiff in the lawsuit who lives in Green Bay, in Senate District 1. "I just don't comprehend that, even what was the purpose here. Somebody quits, resigns, moves on, why not fill their job? We're either saying that the role of a state senator is important or we're not."

One of the more specific issues raised by in the lawsuit was the calendar of legislative business in Wisconsin. Walker and Schimel argued that holding special elections would be moot since the Legislature's standard calendar would be concluded by the time new officeholders could be seated, even if they had been called upon the Dec. 29, 2017 resignation date.

However, the plaintiffs raised the matter of voters in the vacant districts not being represented in special sessions, of which there have already been two in 2018, which was noted by the court. Indeed, Reynolds pointed to the federal lawsuit over the state’s legislative districts and said the potential for a special session addressing its outcome was "very conceivable."

But the prospect that emerged almost immediately after Reynolds issued her order was an extraordinary session of the state Legislature, a new layer of unprecedented action to extend this dispute.

A legislative gambit

After Judge Josann Reynolds issued her ruling for special elections to be called, Wisconsin Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, R-Juneau, signaled that he was considering an additional legislative session. It would focus on passing a law to change the state's special elections statute, and seek to nullifying the circuit court order.

In a March 22, 2018 interview with Wisconsin Public Radio's Central Time, capitol bureau chief Shawn Johnson discussed Fitzgerald's opposition to special elections for the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats.

"It gets pretty thorny," Johnson said. "It sounds like the first path Fitzgerald would like to see is a court stay that blocks the judge's ruling. But if that doesn't happen, he's looking to the Legislature."

Johnson noted the ability of the Legislature to hold an extraordinary session.

"They can come back whenever they want," he said. "Even if it's not in their regular calendar, they can always find, the Legislature, a way to come back in some kind of a session to deal with a bill like this, if the votes are there."

On Friday, March 23, one day after the court order, the Wisconsin Legislature's leadership staked out their position. In a joint press release, Fitzgerald and Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, castigated the court's ruling and raised concerns about how the timeline of any special elections would intersect with the fall elections process.

"It's clear that little thought was given to the impact of the special elections ruling," they stated. "In essence, there will be two elections occurring simultaneously for the two offices. It will lead to voter confusion and electoral chaos."

Gov. Scott Walker issued a similar statement.

"Nomination papers for any special elections called now would circulate around the same time nomination papers circulate for the November election," the governor said. "It would be senseless to waste taxpayer money on special elections just weeks before voters go to the polls when the Legislature has concluded its business. This is why I support, and will sign, the Senate and Assembly plan to clarify special election law."

In a March 23 interview on Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now, Shawn Johnson noted the speed of these responses to the court order, and that the business of the Legislature is ongoing with this proposal.

"We've got a stack now of special sessions and extraordinary sessions after this one gets called, where the Legislature keeps extending that calendar that was maybe going to end in February and now who knows," he said.

Specifics about the Republican proposal took shape three days later, after the weekend.

Writing longer legislative vacancies into law

On March 26, the state Senate released proposed special election legislation language as an amendment to an already-passed bill, and scheduled an extraordinary session to address it, to be held nine days later on April 4.

The proposed legislation sought to significantly change how Wisconsin goes about filling legislative vacancies, by limiting the windows for when special elections can be called, lengthening the period for which open seats would remain unfilled, and applying retroactively to the two vacancies at dispute in Newton v. Walker.

"No special election for the office of state senator or representative to the assembly may be held after the spring election in the year in which a regular election is held to fill the seat," read analysis provided by the Legislative Reference Bureau about the amendment.

The changes also sought to double the amount of time between when a governor calls a special election and the date it is held, from 62 to 77 days to 124 to 154 days. This increase would effectively block any special elections from being held when a vacancy arises in December of an odd-numbered year and throughout the following even-numbered election year. More seats would remain open for more than a year, with voters unrepresented during more regular and special sessions.

What would be an unprecedented aberration in the length of the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 vacancies should they remain unfilled would be made into a new norm.

Trying to buy time

On March 26, the same day the proposed special election legislation was released, the Wisconsin Department of Justice filed an emergency motion in Newton v. Walker for the court to extend the deadline for its order by eight days, to noon on April 6.

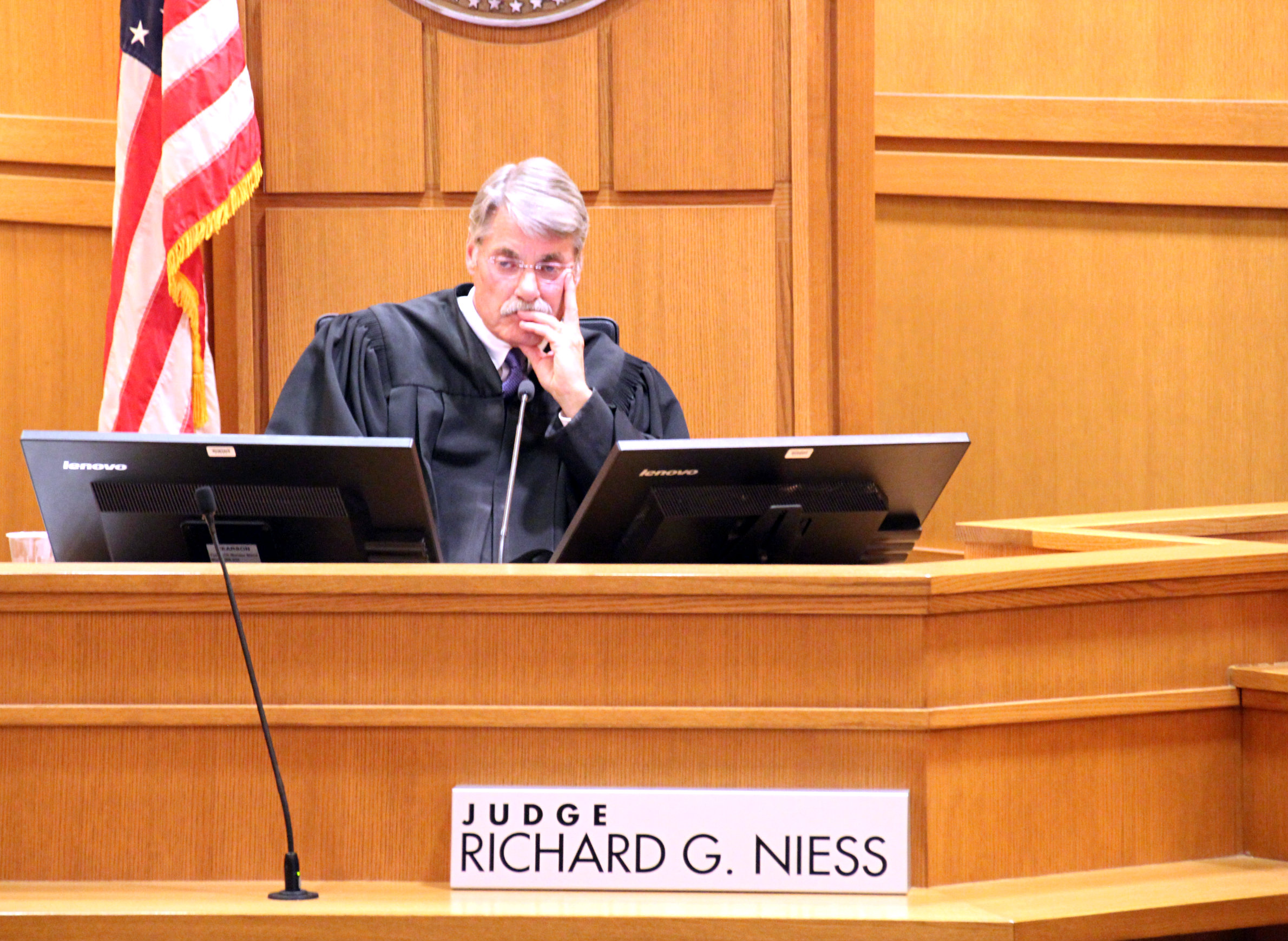

The next day, March 27, Dane County Circuit Court Judge Richard Niess held a hearing on that motion.

In an interview on WPR's Central Time shortly before the hearing got underway, Shawn Johnson described the proposed legislation and noted its tight timeline.

"Why today's hearing is important is that without the court essentially changing its initial ruling, Governor Walker either has to call these elections, even though he knows the legislature is going to change the law, or he would not call them and be in violation of a court order," Johnson said.

What about the legality of the Legislature changing a law in the face of a court order, and retroactively so?

"I'm sure that's going to be a question that is argued over in court and potentially, ultimately decided by our state Supreme Court if the Legislature were to pass this law," Johnson added.

State Department of Justice lawyers argued at the hearing that they were simply seeking the court to delay its order to allow the Legislature time to consider the proposed amendment. The judge was skeptical.

"You're asking that I suspend or reschedule the mandatory act by Gov. Walker to allow the Legislature to take up a bill that's going to affect the voters in Assembly District 42 and Senate District 1 when they have no say in that bill at all," Niess said.

"What you're telling me is that this court, instead of enforcing what has been found to be the law, should suspend that enforcement because of something that might happen in a bill that's in the Legislature," he added in response to the defendant's lawyers.

Niess promptly denied the emergency motion to delay the March 29 deadline, saying that the court was not able make presumptions about what the Legislature may or may not pass.

"I am not ruling on what the law might be in the future," he said. "I am enforcing the law as it is now."

After Niess' ruling, WPR's Central Time once again interviewed Johnson, who noted the judge's stance on even considering the role of proposed legislation.

"That was his point in a nutshell, is that it's not the place of a judge to speculate on what the Legislature might pass next week, he couldn't guarantee that," Johnson said. "He said he has no idea if the Legislature is going to go, quote, lockstep on this proposal and whether it will indeed become law."

This new circuit court decision was not the end of the line for the dispute, though. The emergency motion noted that Walker "will need to seek emergency relief from the appellate courts if unsuccessful here." One day later, the state's lawyers took that step.

A last-ditch appeal

On March 28, Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel and other state Department of Justice lawyers filed an emergency motion in District II of the Wisconsin Court of Appeals. This appeal sought for the circuit court order to be delayed for eight days, until April 5, in order to provide the state Legislature time to pass the proposed bill amendment changing the Wisconsin's special election laws.

That same day, a Wisconsin Senate committee heard testimony about the special election legislation. Legislators sparred over the substance and timing of the proposed changes, as well as about the potential cost of elections for the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats.

Wisconsin Elections Commission staff counsel Mike Haas, the body’s former administrator who stepped downfrom that position after the state Senate refused to confirm him in that position, testified about estimated costs for special elections, making comparisons to those for the spring 2017 and fall 2016 elections. Walker and other Republican opponents of special elections for these seats consistently raised the issue of cost as an objection to calling them.

When asked by WisContext in February about estimated costs of special elections for the open seats, Commission spokesperson Reid Magney did not provide any figures, saying the organization doesn't collect cost reports for most special elections, and noting that expenditures can vary based on location and turnout. Likewise, when reached for comment in February, a Walker spokesperson declined to cite specific figures, claiming that any cost would be too much.

Had Walker promptly called special elections in the two vacant districts upon the resignations of their former officeholders, though, the votes could have been conducted on the date of the regular spring election, avoiding additional costs. This matter of timing was noted by Democrats in the hearing, as well as in public statements about the controversy. However, elected officials and members of the public who criticized the governor's inaction emphasized that the right of citizens to have a voice in representative government does not have a price tag.

The court of appeals shared that view, and declined to assign a dollar figure to an essential mechanism of representative government.

On the afternoon of March 28, Wisconsin Court of Appeals District II Judge Paul F. Riley denied the emergency motion filed by the state Department of Justice on behalf of Walker. In the ruling, Riley indicated that the governor and courts have an obligation to follow the state's current special election law. He also rejected arguments related to the cost of special elections.

"Representative government and the election of our representatives are never 'unnecessary,' never a 'waste of taxpayer resources,' and the calling of the special elections are as the Governor acknowledges, his 'obligation' to follow by virtue" of existing state law," wrote Riley.

Facing a deadline of noon the next day with the circuit court order to call special elections, Walker and his lawyers had one final judicial recourse: to appeal to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Before the governor's bid before the appeals court was rejected, the Department of Justice sent a notice to the Wisconsin Supreme Court clerk indicating their possible interest in filing an emergency petition in that forum to delay the deadline.

"If the Governor were to file this emergency petition," the letter read, "he would respectfully request that the Court issue an order granting the Governor's emergency motion (or at least administratively staying the underlying circuit-court order to permit more time for this Court to consider the Governor's emergency motion) if at all possible by 12:00 p.m. tomorrow, Thursday, March 29."

Only hours later, though, following the appeals court ruling, the Department of Justice issued another notice to the state Supreme Court. "Upon further consideration," it read, "the Governor has decided not to seek relief from the Supreme Court at this time" [emphasis in original].

After having their arguments rejected twice in circuit court and once in appeals court, the defense in Newton v. Walker decided not to seek judgement from the highest court in the state.

How the Wisconsin Supreme Court may have ruled on a motion is a matter of conjecture. However, the timing of this legal battle coincided with a race for an open seat on the Court, with the election for it to be held just a few days later. State Supreme Court elections are officially non-partisan, but recent voting patterns in these races align closely with partisan divides around Wisconsin.

On the morning of March 29, a few hours before the court-ordered deadline, Walker issued an executive order that calls special elections for the vacant Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats. Shortly thereafter, state Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald told Milwaukee radio station WTMJ-AM that the Legislature would not take up the proposed special elections legislation as previously planned, while Assembly Majority Leader Jim Steineke, R-Kaukana, issued notice to that chamber's members that there would not be an extraordinary session on April 4. With those plans dropped, Wisconsin's current statutory requirements for legislative vacancies remain unchanged, for the time being.

The national politics of legislative vacancies

Over the course of a single week, a dispute over special elections in Wisconsin and the lawsuit that brought it into the court system swiftly escalated into a political maelstrom. Indeed, the case assumed national prominence as the showdown intensified.

Beyond the serious legal issues at play in the case — what Wisconsin's special election law really means, what are the rights of voters to be represented when there are vacant legislative seats, what is the relationship between the legislative and judicial branches of state government — the accompanying political row has generated a lot of speculation and punditry about the motives of the governor's original inaction on the vacancies and the subsequently intense pushback from Walker and state legislative leadership, all Republicans, on the lawsuit and court order.

At the most basic level, 2018 is shaping up to be a wave year for Democratic candidates, perhaps significantly so. Members of Wisconsin's Democratic legislative delegation issued statements suggesting that the vehemence of the state's Republican leaders' actions was driven by their fear that GOP candidates would be particularly vulnerable in any special elections. Given national political dynamics, particularly the vast partisan split in approval for Republican President Donald Trump and electoral enthusiasm among Democrats, there is a pattern of GOP candidates nationwide underperforming in special elections held in recent months, including a Jan. 16, 2018 vote for the state Senate District 10 seat in western Wisconsin won by Democratic candidate Patty Schachtner.

As for the lawsuit, it was backed by the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, a national political advocacy and campaign group headed by former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, who served in the Obama administration, and the plaintiffs were represented by attorneys from Perkins Coie, a law firm with deep connections to the Democratic Party.

At the same time Walker issued the executive order calling for special elections, he also published a series of tweets decrying that outcome, complaining about the timing of these court-ordered state legislative campaigns, and accusing "Eric Holder and other liberals in Washington, D.C." of making political hay over the matter. In subsequent comments, the governor said he stopped pursuing appeals challenging the lawsuit because the plaintiffs "were able to succeed in court."

In the wake of this series of unprecedented events in Wisconsin politics related to special elections, there is some additional clarity on the law related to legislative vacancies. The circuit court ruling in Newton v. Walker stands, underscoring that the language of state statute section 8.50 applies to all years, not just those when there is a general election for a given vacant state legislative seat.

Left unaddressed in this dispute, though, was language in Article IV, Section 14 of the Wisconsin Constitution that simply states "[t]he governor shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies as may occur in either house of the Legislature." This directive is even more broad and subject to interpretation than what's in state statute, but it sets an underlying duty for governors to fill vacancies.

With the Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 resignations announced on Dec. 29, 2017 and special elections for those seats scheduled for June 12, 2018, those vacancies will end up remaining open for 165 days. That span of time is more than a month longer than every previous instance in which Walker has called for a special election. But the starting point of this particular instance had earlier origins.

The timetable for the two vacancies extended well before Frank Lasee's and Keith Ripp's resignations were announced on the last weekday of 2017. Earlier that year, on Friday, Nov. 10, WisPolitics.com reported on speculation that both legislators would be headed to the Walker administration. It was seven weeks later — 49 days in this preliminary stage of the saga — that their departure from the Legislature was made public.