From The Medicine Cabinet To Lake Michigan

As medications and personal care products pile up in people's medicine cabinets, they are also increasingly making their way into water supplies, accumulating over time in tiny increments. They're called "emerging contaminants," and the effects of these chemicals on the environment and human health have concerned scientists for many years.

A Wisconsin-based study upended longstanding assumptions that vast amounts of groundwater and surface waters — such as Lake Michigan's 1,180 cubic miles of volume — can dilute these chemicals to negligible levels. Researchers from the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences collected water samples near one of Milwaukee's wastewater outfalls on Lake Michigan and dispatched scuba divers to scoop up jars of sediment in the lakebed in the same area.

Led by UW-Milwaukee professor Rebecca Klaper, the research team tested water and sediment samples for 54 pharmaceutical chemicals and hormones. Their findings, published in 2013, indicated many chemicals and hormones were detectable in Lake Michigan, including the common diabetes medication metformin. Overall, multiple compounds were present in concentrations that "indicate a significant threat by [pharmaceuticals and personal care products] to the health of the Great Lakes," wrote the researchers.

Curtis Hedman, a microbiologist with the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, detailed this study's findings in a February 26, 2014, talk for the Wednesday Nite @ the Lab series on the UW-Madison campus, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place. He offered perspective on what these findings mean for human health and aquatic ecosystems. He also provided context about other research in progress in Wisconsin and elsewhere on these contaminants, and on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's efforts to home in on specific chemicals for monitoring and treatment.

Key facts

- Metformin, caffeine, sulfamethoxazole and triclosan were the "most frequently detected" chemicals in the UW-Milwaukee and State Lab of Hygiene study.

- Metformin, a drug often used to treat type 2 diabetes, wasn't studied very much until recent years. Earlier studies might have missed the pharmaceutical because its detection in a water sample requires a specialized extraction method.

- The hormones the study found were largely androgenic, meaning they promote physical traits typically defined as male.

- In sediment samples, the antibiotic azithromycin showed higher concentrations than any other chemical in the study, by a wide margin.

- Five compounds — ciprofloraxin, clarithromycin, micanazole, thiabendazole, and triclocarban — were detected in the lake bed sediment samples but not in the actual water samples. This finding may have been due to these chemicals' ability to bind with the sediments, and/or because sunlight and microbes break them down when they are in the water.

- Research on pharmaceutical chemicals in water supplies really took off in 2000, due to the efforts of a research team with the U.S. Geological Survey. This group looked at streams across the country. They searched for a wide array of compounds, including antibiotics, hormones, and household industrial compounds. They found antibiotics in 80 percent of the drinking water samples they studied.

- Tetracycline was the most prominent antibiotic found in the study, but water treatment eliminated it almost entirely.

- Other studies have found that some food and drink products have higher concentrations of some pharmaceutical compounds than drinking water.

- Even when the detected concentration of a compound doesn't have a significant impact on human health, it may still harm fish and aquatic microorganisms, with consequences that reverberate throughout the food chain. Of the chemicals the UW-Milwaukee and State Lab of Hygiene team analyzed in its Lake Michigan study, caffeine and paraxanthine present the greatest risk to fish and other aquatic organisms.

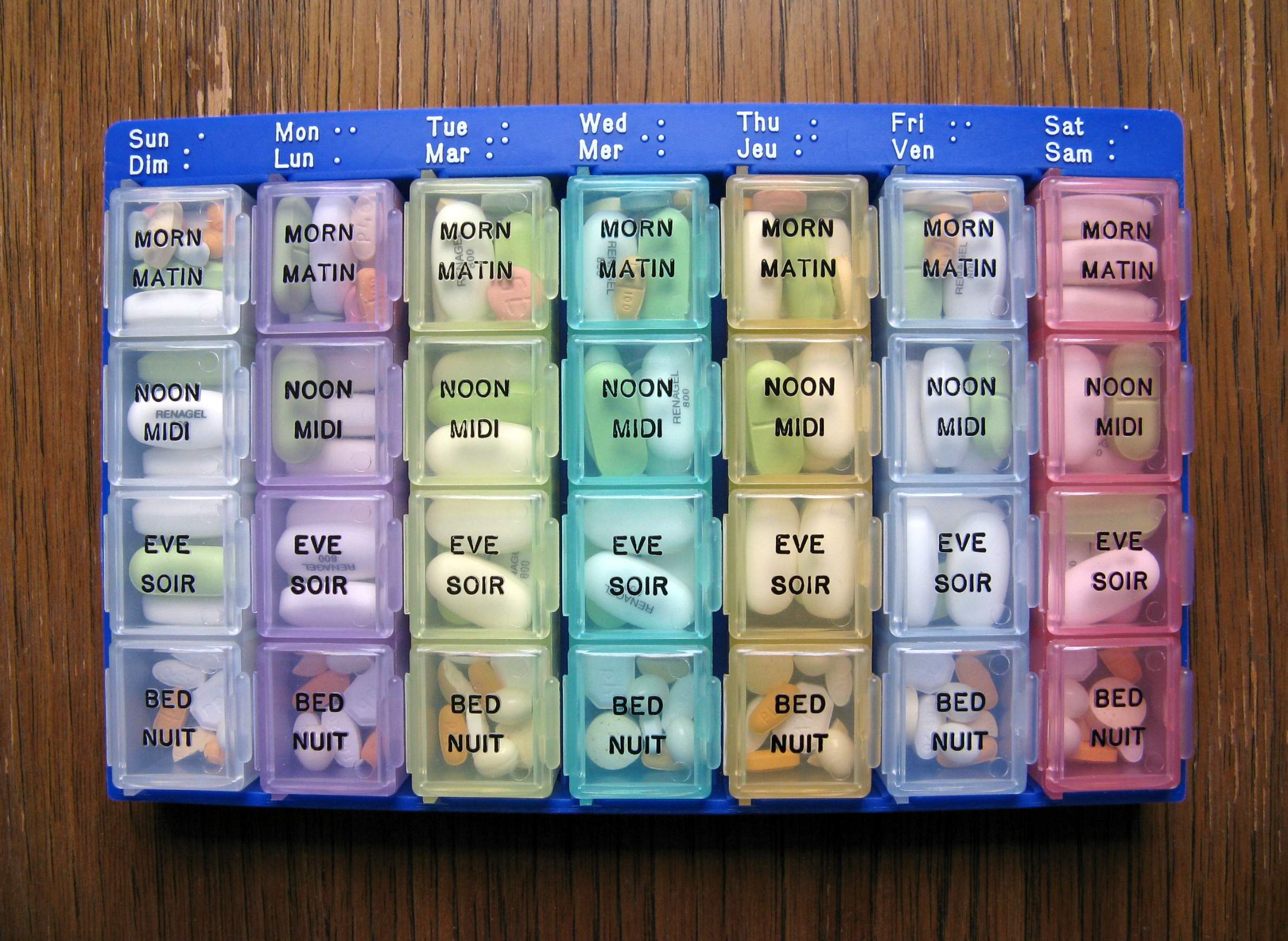

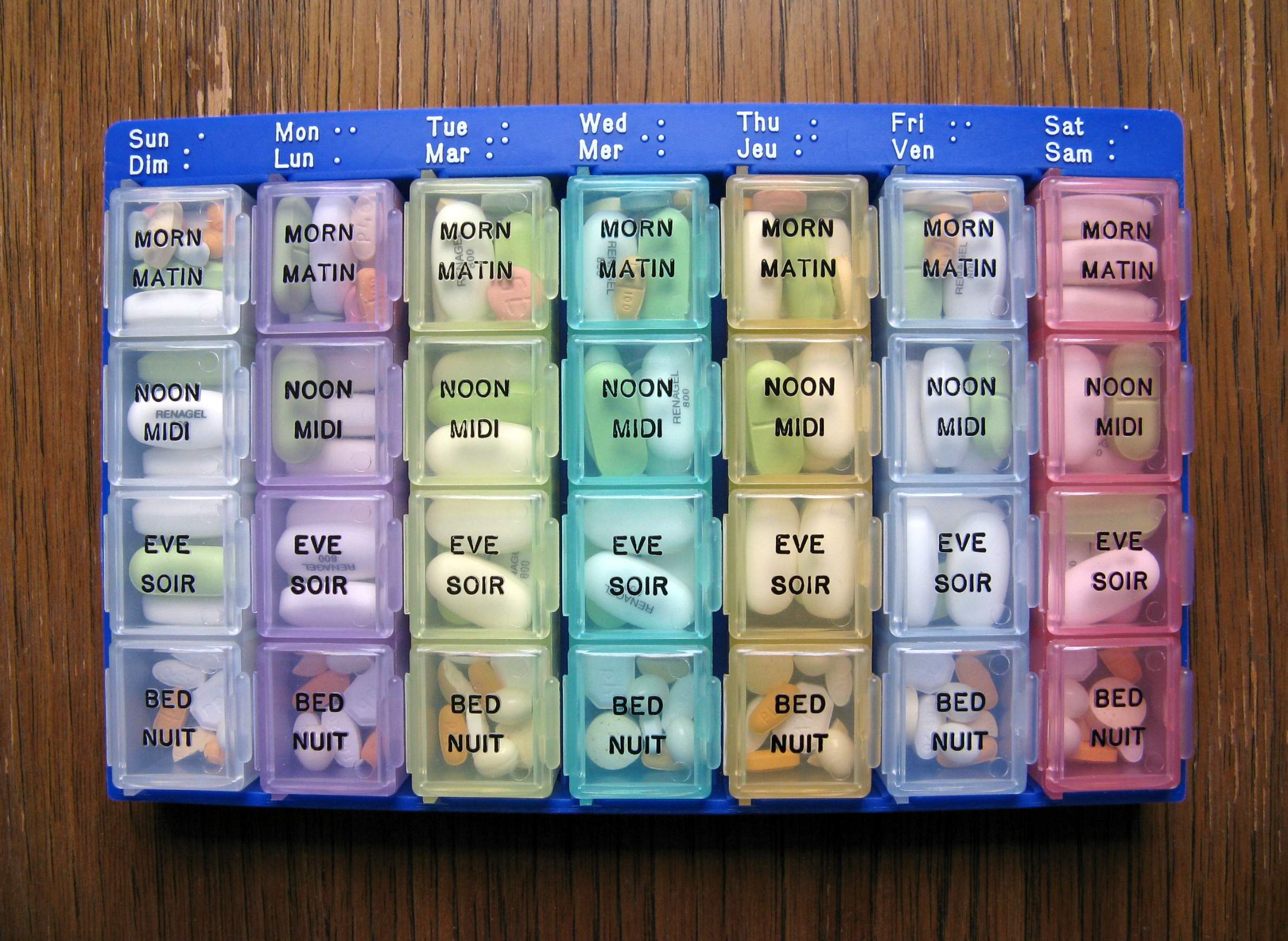

- Federal, state and local officials are trying to keep pharmaceuticals out of the water with drug-takeback programs, including one in Curtis Hedman's hometown of Stoughton.

Key quotes

- On metformin in the water: "I don't know if that makes a comment on where we are with society, if the number of people are taking metformin and it's ending up in the harbor in those concentrations."

- On the chemical persistence of pharmaceuticals in the water: "Even though they might break down in the environment over time, you get a certain pseudo-steady-state concentration because they're constantly being put into the water from the wastewater treatment facility."

- On Milwaukee officials' water-monitoring methods in the early 1900s: "They kept track of the wild rice growing close to those outflows and figured if the wild rice was growing, everything was OK, so we've come a long way in several decades."

- On the challenges of tracking pharmaceutical chemicals in drinking water: "The methods that we're using are looking at unique targets. We have to know what we're looking for, optimize the compounds so we can detect it at such low levels. I'm looking at several dozen, and the USGS lab is looking at a couple hundred. Well, according to the [Government Accountability] Office, we have more than 7 million recognized chemicals and approximately 80,000 in common use in industry. So, you start to think about, how can we even hope to track what's being put in the environment and determine what in that mixture might be causing toxicity at a low level? So, to make a complicated situation worse is that it's tough for the U.S. EPA to look at that huge amount of compounds and then determine, which ones do we really focus on with the resources that we have?"

- On the implications of the research, as stated in a Nov. 15, 2013 Q&A published by the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene: "Protecting aquatic organisms is important in that even a subtle change in the behavior or survival of one aquatic population can cause large scale problems or even collapse of an ecosystem. These aquatic organisms are also considered 'sentinels' for eventual human health effects if contaminant levels continue to occur and potentially rise, unchecked."