How Possible Is It To Cut Wisconsin's Prison Population?

Investing in people, not prisons, is what Gov. Tony Evers believes the state of Wisconsin should be doing.

During his 2018 gubernatorial campaign, Evers was vocal about criminal justice reform, outlining a number of policies he would like to see changed and saying that reducing the prison population by 50 percent is a "goal that's worth accomplishing." Already, the state's prison system is 33 percent above capacity.

But with a Republican-controlled state Legislature that lookied to curb the Democratic governor's power before he's even in office, Evers is likely facing an uphill battle in trying to reduce the state's prison population and implement changes in criminal justice policies.

A growing prison population

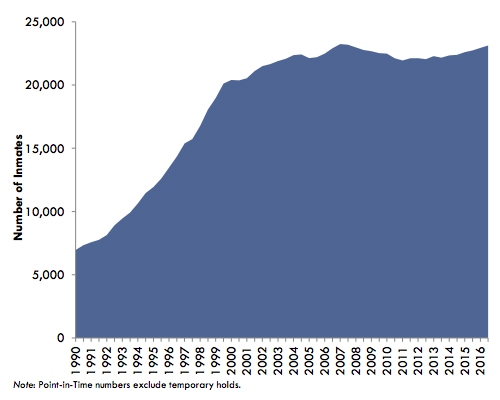

As of Nov. 30, 2018, Wisconsin had a prison population of 23,637 — a number that's expected to increase by almost 6 percent in the next three years.

According to a report released in October by the nonpartisan, independent policy research organization Wisconsin Policy Forum, by 2021, the number of inmates will grow to more than 25,000.

While this would be a record number of inmates, the increase isn't as rapid as it was during the 1990s when the state experienced a 174 percent increase from 1990 to 2000.

To deal with the expected increase, the Wisconsin Department of Corrections is requesting an additional $149.4 million in the 2019-21 biennial budget.

The DOC, unlike most other state agencies, is funded entirely out of state income and sales tax, Wisconsin Policy Forum spokesperson David Callender said.

"Prisons are almost exclusively a state operation, so when there's an increase [in request for funding], that obviously means there are going to be other programs that either won't get that money or will have to compete for that money," Callender said.

Part of the budget request is to convert the Lincoln Hills juvenile facility, which is slated for closure by 2021, into an adult facility, Callender said. Right now, the design capacity for the state's adult prisons is 17,829, according to the DOC — roughly 5,800 below the current population.

Another part of the request is increasing the use of contract beds over the next few years, meaning that DOC would pay for space in county jails to house inmates, Callender said. Something the DOC is not talking about, Callender said, is sending inmates to out-of-state facilities, which was an action that was taken in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

So, how did this increase happen?

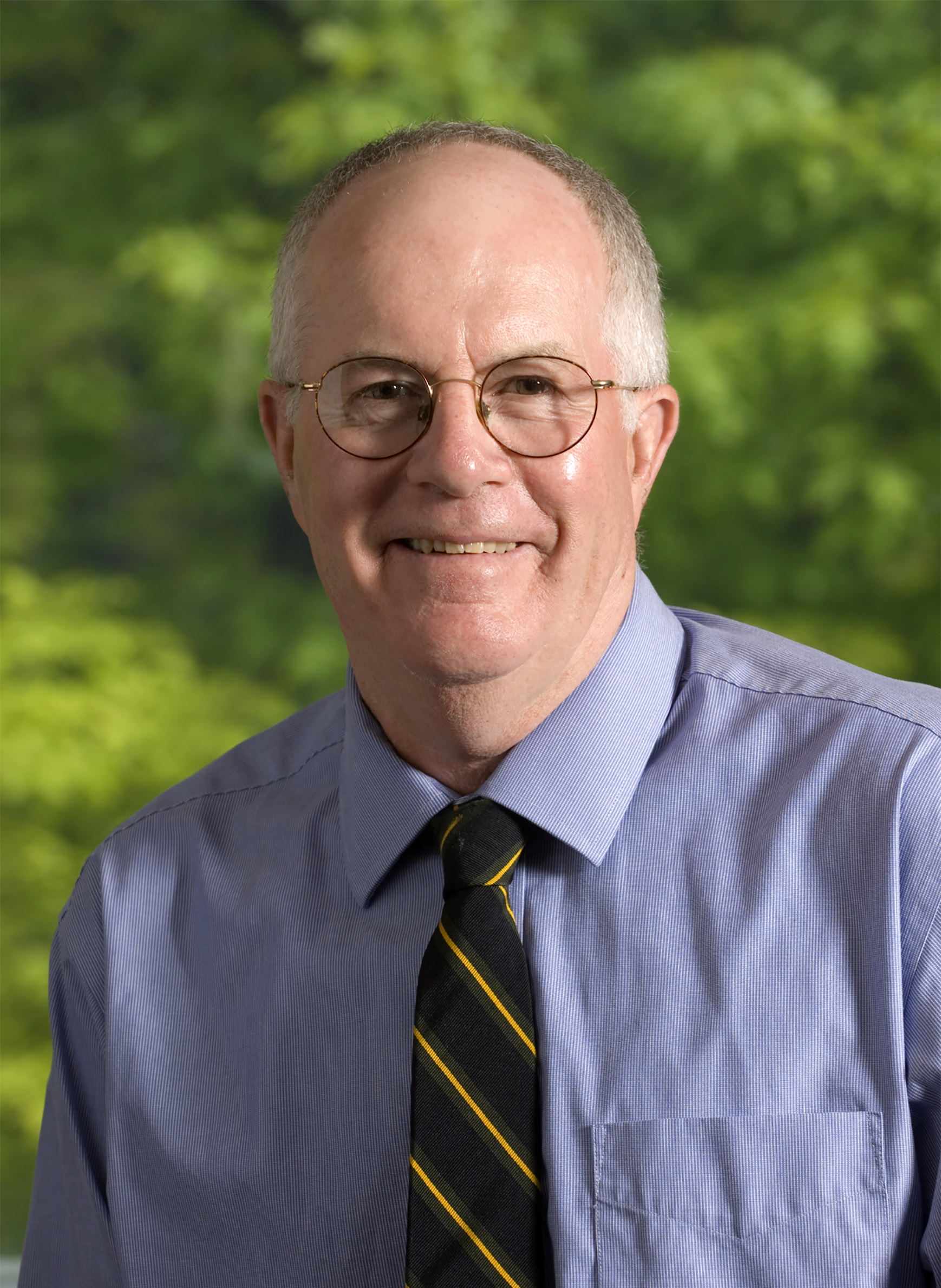

University of Wisconsin-Madison professor emeritus of law Walter Dickey believes truth-in-sentencing legislation has been a major driver of the rising prison population. Dickey was secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections from 1983 to 1987 and serves on Tony Evers' criminal-justice reform committee.

Prior to truth-in-sentencing, offenders were eligible for release after serving 25 percent of their time and received a mandatory release date after serving two-thirds of their time, after which they were paroled. Under truth-in-sentencing legislation, which first took effect in 2000, traditional parole was virtually eliminated for newly convicted offenders.

Currently, only about 5 percent of so-called old-law inmates who are parole-eligible are granted release, according to David Liners, state director for WISDOM, a grassroots organization seeking to end mass incarceration.

"That whole [parole] system is just broken down, and it's a nightmare," Liners said. "Common reasons people are given for having their parole denied, are 'insufficient time served' or somehow releasing them would be an 'unacceptable risk to society' — there's no definition for either of those things."

Under truth-in-sentencing, offenders receive a bifurcated sentence, which includes the time they're supposed to spend in prison and the time they'll be on extended supervision following their release. The time spent on extended supervision has to be at least 25 percent of the prison sentence.

While extended supervision is similar to traditional parole in the sense that there are certain conditions that need to be met, the difference is the individual can go back to prison for the entire term, David Callender said.

"Let's say that you have three years on extended supervision. If on the very last day you commit an offense and have to go back to prison, you could potentially go back for that entire three years," Callender said. "Generally, the longer that somebody is looking over your shoulder and the longer you're under supervision, the more likely it is that you may do something wrong and end up back in prison."

In fact, in 2017, 36.5 percent of prison admissions in Wisconsin were related to violations of probation, extended supervision or parole — not new crimes, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum report.

While someone is on extended supervision, there are three main ways supervision can be revoked: a new sentence; a revocation plus a new sentence; or a rule violation, which the DOC calls "revocation only" and WISDOM calls "crimeless revocation." The largest segment of prison admission is people who are coming back due to revocation only, Callender said.

Some of the rules people have to follow while on extended supervision can be pretty specific and detailed, like not being able to borrow money without permission or being late to an appointment with an agent, Liners said. Others are more straightforward, such as failing a drug test or not attending a specific program.

"It's hard to keep all these things straight," Liners said. "In some cases, it is that people have messed up, but in that case, I don't know that reimprisonment should be the default way to deal with it."

A piece of data Callender said is missing is what is driving the revocations and what the most common revocations are.

"Are these serious violations of protocols that individuals need to be returned to prison in order to protect society, or are they minor offenses that perhaps could be addressed some other way?" Callender said. "That's one area of data the Department of Corrections really doesn't have yet."

When asked about data on revocations, DOC spokesman Tristan Cook sent a link to the "up-to-date and complete data on admissions to prison for revocations," but this data did not include information about the types of violations offenders are committing.

How possible would it really be to lower Wisconsin's prison population by 50 percent?

During the gubernatorial election, then-Gov. Scott Walker claimed cutting the prison population in half would require the release of thousands of violent offenders into the community. PolitiFact checked Walker's claim and found it to be "Half True."

While a short time frame for Tony Evers' goal might require the release of violent offenders, a longer time frame could achieve this goal without the release of any violent offenders, according to PolitiFact.

Evers has not outlined a timeline and was spending his transition period talking with members of the corrections community and the Legislature before anything is announced, Evers' transition spokeswoman Carrie Lynch said.

Around two-thirds of Wisconsin's inmates are incarcerated because they have committed a violent offense. There's a public perception that prisons are full of nonviolent offenders, but overall, that has never been the case, Wisconsin Policy Forum's David Callender said.

"That's where it creates some complexity in terms of being able to immediately reduce the prison population because there is not necessarily a lot of low-hanging fruit in the population," Callender said. "There are individuals I think potentially could be released, but again, it's a much more complicated situation."

With Wisconsin's current sentencing system, Walter Dickey believes cutting the prison population in half would be extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible. Traditional parole has been abolished and sentences, for the most part, cannot be shortened.

Dickey said changing sentencing laws would be "much more desirable" but would need to be done by the Legislature, which is currently run by Republicans. While Liners sees the Legislature addressing sentencing laws in the long term, he doesn't see it happening in the coming year.

Judges can adjust sentences, but this isn't a realistic method for reducing the prison population because it would take willing judges and a return to court for each case, Dickey said. In a May 2017 report, the nonpartisan Badger Institute found that sentence adjustment petitions are rarely approved. Out of the 2,288 petitions filed in 2016, 295 were granted.

Dickey said he believes state leaders first need to agree on a purpose for prison.

Two possible purposes could be just punishment and public safety — both of which Dickey believes are hard to disagree with. Once the purposes for prison are figured out, then the possibility for discussion opens up on how to use sentencing and community corrections to achieve these goals.

"Prison is for the people we're afraid of — not the people we're mad at," Dickey said. "We ought to be using prison as a means to achieve public safety, and if we have people who don't 'need' prison because they're not a public safety threat, then we shouldn't be using prison for them. We should be using some other kind of correctional resource."

David Liners said the prison population could be reduced by at least 8,000 in two years if steps are taken to end crimeless revocations, fix the parole system and expand Treatment Alternatives and Diversion programs.

The governor has a lot of latitude when it comes to ending crimeless revocations and fixing the parole system, and TAD funding comes from the state budget, Liners said. Funding for TAD programs usually gets bipartisan support, so there’s a good chance if an increase in funding was proposed, the state Legislature would go along with it, he added.

"Treatment Alternatives and Diversion saves all kinds of money, so it's fiscally really responsible, and the recidivism rate is much lower for people who get into TAD programs than it is for the equivalent people who go to jail," Liners said. "Whichever thing we're trying to do — save money or reduce crime — they both have the same answer."

For Evers, it comes down to investing in TAD programs and drug courts because both will help reduce the prison population, Lynch said. During his campaign, Evers also stressed the importance of looking at crimeless revocations and the impact it's having on the state's justice system.

On Dec. 10, Evers and Lt. Gov.-elect Mandela Barnes announced their Public Safety and Criminal Justice Reform Policy Advisory Council. Both Liners and Dickey were named part of the council that is "bringing together people from all sides of the criminal justice system … on exploring solutions for reforming Wisconsin’s criminal justice system."

Evers noted that red states including Texas have passed comprehensive criminal justice reform with support from both sides of the aisle — something he's confident Wisconsin can do.

Said Liners: "We either need a new prison or we need to do something about the capacity. Take these other steps first, because we don't think you'll need the new prison."

Editor's note: This report was originally published on Dec. 13, 2018 by The Observatory, a publication of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

This report is the copyright © of its original publisher. It is reproduced with permission by WisContext, a service of PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio.