For Formerly Incarcerated Milwaukeean, Housing Is Key To Rebuilding His Life

Andrew Hopgood spent eight years going to sleep and waking up in a prison cell serving time for a robbery charge. When he was released in 2008, he lost the shelter prison provided him every night, and he faced the very real problem of where to stay.

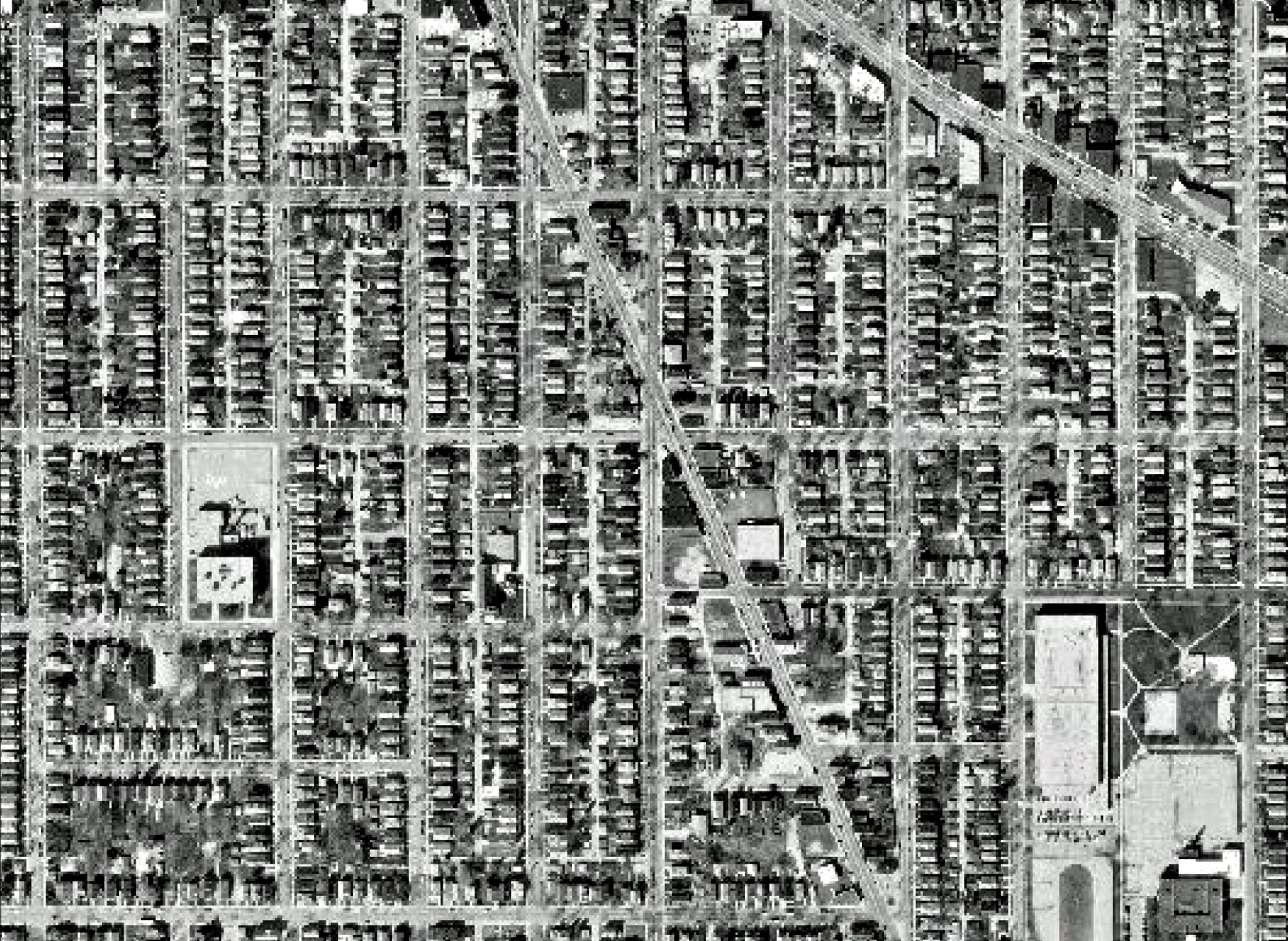

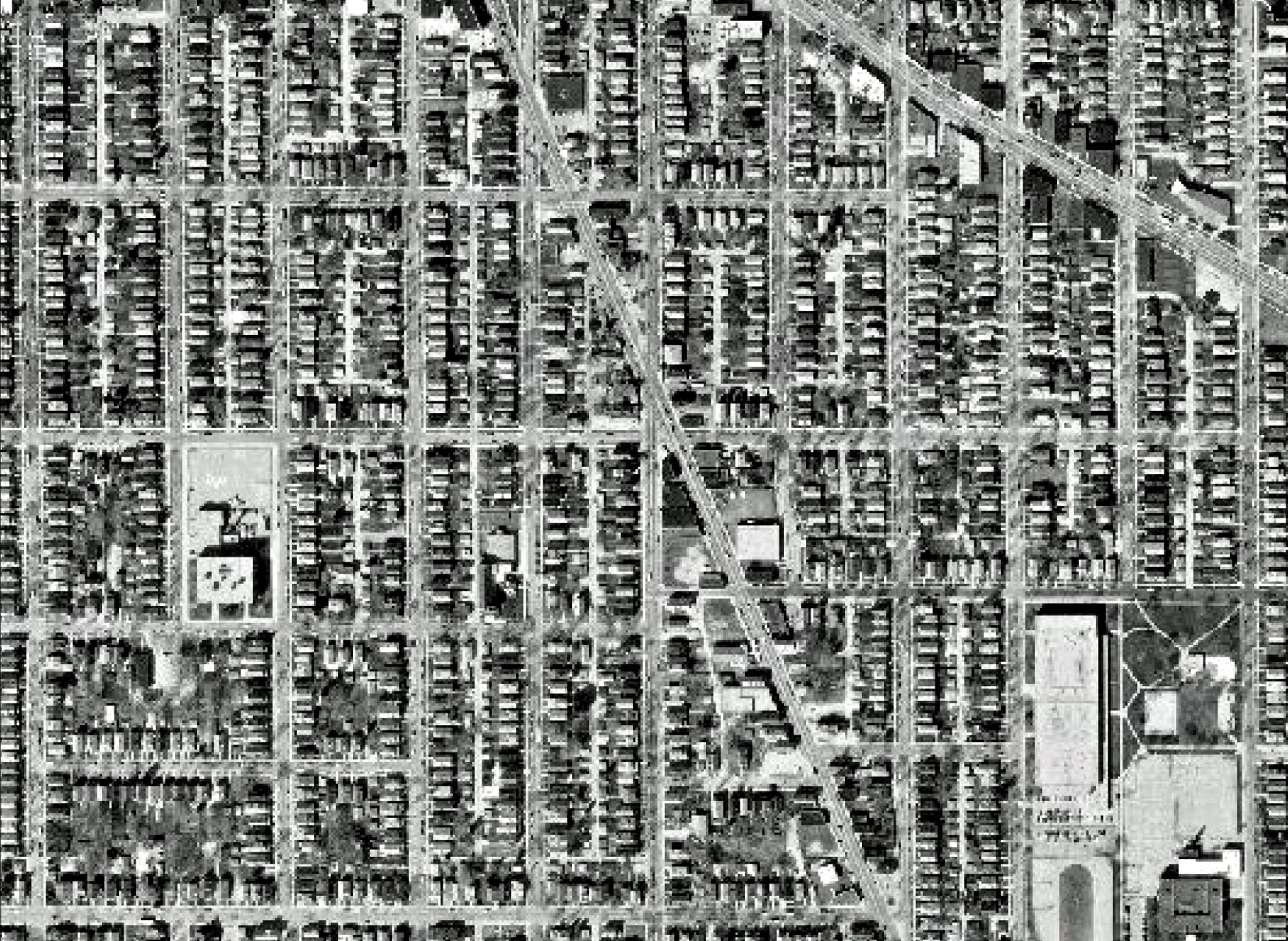

As a Milwaukeean, Hopgood is not the only one facing this struggle tied to reintegrating into society after being incarcerated. The city has a disproportionately high number of residents who spend time behind bars – in the northwest Milwaukee ZIP code 53206, nearly a third of adult men have spent time incarcerated.

Some formerly incarcerated people and community advocates believe stabilizing their neighborhoods begins with better housing options, post-release.

Upon his release, Hopgood initially stayed with family, but it didn't work out – an outcome not uncommon for those who have served time.

"When I got out, I stayed with my dad for a while," Hopgood said. "That got kind of hard for me because I had a hard time finding a job, and I couldn't pay the rent. Things got so bad between me and him, we almost came to blows, and I just left."

Hopgood's story is familiar to University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Professor Thomas LeBel, who studies criminal justice.

"Some studies have suggested that perhaps 10 percent or more of people returning home from prison (nationwide) might be homeless at some point in the first year or two after they're released from prison," LeBel said.

Within six months of his release, Hopgood found himself as a member of that 10 percent. When he left his father's home, he had no job or income.

"I know what it's like to have slept in empty abandoned cars," Hopgood said. "I know what it's like to have walked the streets all night in the cold and not have anywhere to go. I know what it's like to have slept in the drug house all day, all night long, waiting on daylight because I didn't have anywhere to live."

Hopgood said a lack of housing made it impossible to get his life back on track.

"If you're not stable in your living and have no place to live, it's hard to function," Hopgood said. "It's hard to concentrate on working a job, and getting off work every day and you don't have anywhere to go."

After four months of living on the street, Hopgood said, he caught a break when his friend introduced him to a woman who ran a shelter. This shelter allowed him to look for a job and focus on overcoming his drug addiction. Other shelters had restrictive curfews or didn't allow him the freedom to search for a job.

Hopgood also started going to Project Return, a program helping formerly incarcerated people reintegrate into society. He's been going there for more than a year.

The organization's executive director, Wendel Hruska, said the lack of housing for formerly incarcerated people such as Hopgood is a problem he sees every day.

"The concern for landlords to be able to rent to those individuals is because they don't know if they're going to be here a month, a couple months, or if they're in for the long haul," Hruska said.

Hopgood has been able to find a way around that barrier. He now lives in a facility that's rent free until a resident has an income. After that, rent is capped at 30 percent of their earnings. The stability has allowed him to pursue an education at Milwaukee Area Technical College and set career goals.

"I want to work with the homeless and people who are addicted," Hopgood said. "I just want to be able to assist people. To encourage people to come away from that lifestyle."

But, if Hopgood ever decides to look for a place of his own, he will have to deal with the stigma of once being in jail.

"They figure once you're a criminal, you're a criminal," Hopgood said. "Once you've done something wrong, that's who you are. It's all about forgiveness, it's all about putting yourself in somebody else's shoes."

Advocates such as Hruska remain hopeful this challenge will become easier. He said what it comes down to is people being willing to give former felons a second chance.

"Take it on a case-by-case basis," Hruska said. "We tend to group everybody into one pocket. We tend to group people together, and the reality is that just because people might have committed a similar offense, does not mean they are in a similar mindset."

The Milwaukee Common Council recently voted to eliminate questions about past convictions on employment applications. Hruska said if efforts like this translate to housing, prisoners can start to believe they actually have a chance of finding a place to live and the stability that comes with it.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2023, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.