How To Smell A CAFO

Russ Hanson is determined to live a better retirement than his in-laws did. For him that means steering clear of the odors that can accompany large livestock farms.

Hanson has lived most of his adult life in rural southeast Minnesota, but he recently retired to the family farmland of his childhood, straddling Burnett and Polk counties in northwest Wisconsin. The region has changed in the decades since Hanson's youth, though; in 2019, his neighbors are more likely to be fellow retirees or part-timers attracted to the counties' lakes than working farmers.

But a proposal to build what would be Wisconsin's largest hog facility in a crop field not far from Hanson's home is throwing his rural Wisconsin retirement dreams into doubt. It's also bringing back memories of his in-laws' final years on their farm in the community of Cheeseville, located in the town of Farmington in Washington County. Just a short drive from West Bend and near the headwaters of the Milwaukee River, they lived a quarter-mile east (and thus usually downwind) of a dairy farm that began expanding in the early 2000s. Within a few years, that operation grew from a few dozen to hundreds of cows.

Intense and incessant odors drifted the short distance to his in-laws' home from large, open-air lagoons where manure was stored, Hanson said. He described those odors as a "mixture of ammonia, rotten eggs and dead animals." The odors upended life for his in-laws, he said, by forcing the social and outdoorsy couple to remain indoors much of the time and to cancel planned gatherings at their home. Eventually, around 2010, they gave up and moved after accepting a low-ball offer on their property.

Those experiences have remained with Hanson so viscerally over the last decade that he said there’s no question what he would do if a large livestock operation — hog, dairy or otherwise — were to set up near his home.

"I would move," he said. "If it's within a mile, it's not tolerable."

A big pig farm

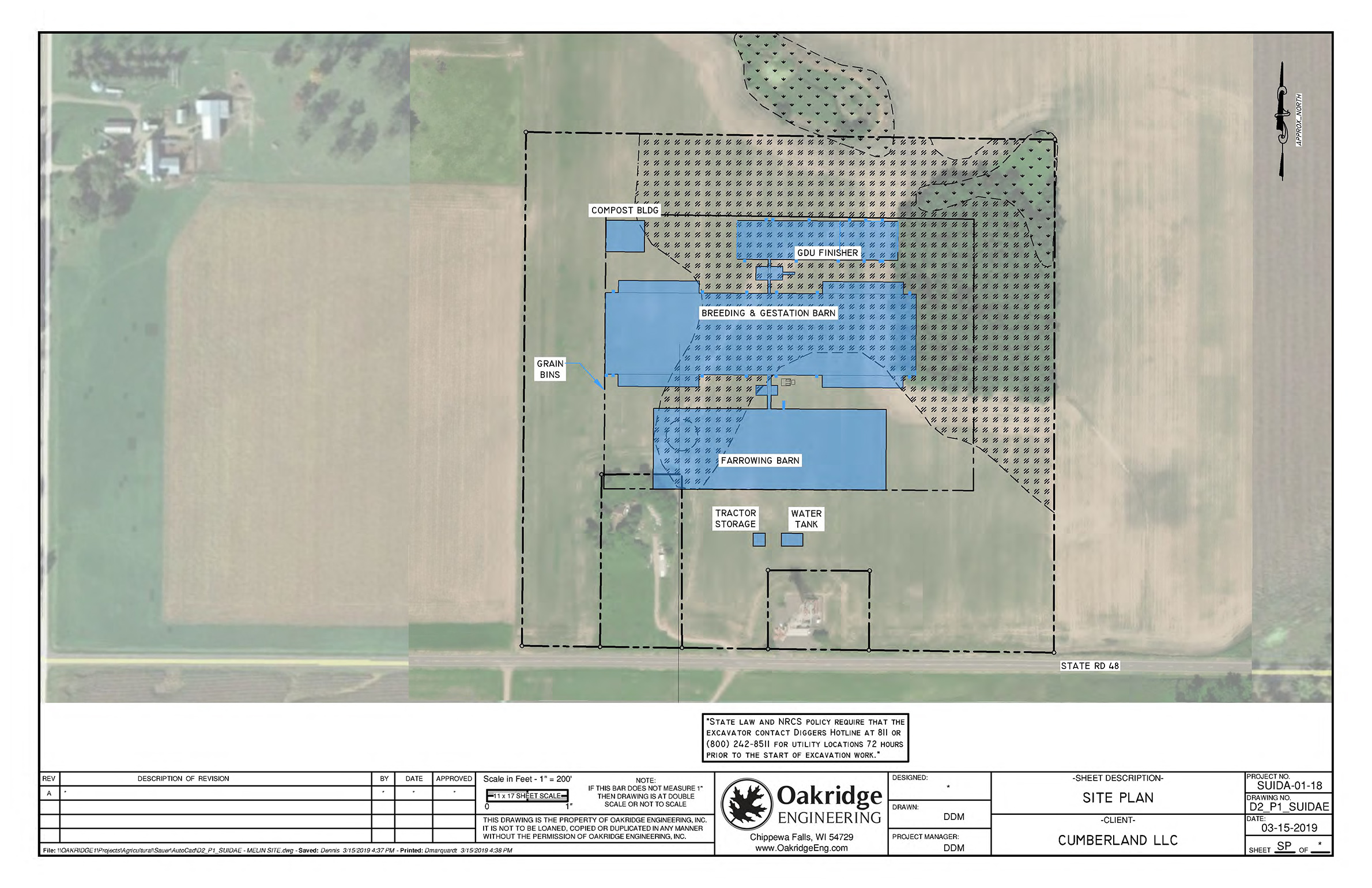

The livestock facility proposed near Hanson's home in Trade Lake would house 26,000 hogs, well over the number that triggers mandatory environmental oversight from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. These large livestock farms, known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, offer their operators efficiency and potentially higher revenues. They also amass animals and their daily output of manure to such a degree that they can pose an environmental hazard to local water and air quality, a risk that many potential neighbors consider untenable.

In Trade Lake, many neighbors of the would-be hog operation are anxious over the proposal, as explored in an Oct. 19, 2019 segment on Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now.

"I believe it was in May [when] I started getting calls from people in Trade Lake," said Dorothy Richard on Here & Now. Richard represents the Trade Lake area on the Burnett County Board of Supervisors.

"What I'm most concerned about is our water," she said.

The DNR's CAFO oversight responsibilities are focused on water quality, but odors are often what drive tensions between large livestock facilities and their neighbors. As was the case for Russ Hanson's in-laws, Wisconsin's "right-to-farm" law means neighbors don't have much legal recourse if they perceive a farm's odors to be a nuisance.

That's why many rural landowners like Hanson increasingly view their options as either stopping the construction of a large livestock facility before it moves forward, or moving away as quickly as possible.

"Unless you live downwind from one of these farms on a hot August day, you can't really know how intense, pervasive and rotten it smells," Hanson said.

But rotten smells are an entirely different challenge to regulators than water contamination. How can odors be measured and quantified in a systematic and fair way? Is it even possible to break down an odor into its component parts, or to identify an acceptable odor threshold?

It turns out these questions are the subject of rigorous scientific research. In fact, cataloguing livestock odors and tracking how they move across the landscape represent whole areas of research that help inform Wisconsin's rules about where regulated livestock facilities can be placed. But as the scientific study of odors and odor management evolves, the state's livestock siting rules may also soon be changing.

The subjectivity of smell

Scientists who research odor detection and management have the tricky job of systematizing a complex and subjective sensation.

"Everyone will experience an odor differently," said Erin Cortus, an assistant professor in the Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering at the University of Minnesota. Cortus studies air quality through the lens of gaseous agricultural emissions.

Various gases and gaseous compounds contribute to livestock manure odors, she said. Chief among these are ammonia and hydrogen sulfide.

More familiar as a cleaning agent, gaseous ammonia originates in urine and has a strong odor that reminds many people of bleach. Meanwhile, even at extremely low concentrations, hydrogen sulfide can produce an odor that is commonly described as reminiscent of rotten eggs. (At slightly higher concentrations that only occur under certain conditions in the immediate vicinity of manure facilities, this gas becomes odorless and is extremely hazardous to human health). Together, these two gases make up a good portion of odorous cocktails emanating from livestock farms.

But gases are only one piece of the olfactory puzzle.

"An odor is also made up of a lot of other volatile organic compounds," Cortus said. "Some of which are in very minute quantities but can be very powerful."

These organic compounds originate in farm byproducts like animal feces. Manure is essentially digested organic matter and bacteria. The precise mixture of gases, organic compounds and other chemicals — collectively called odorants — that wafts from a livestock farm depends on the type of animals excreting the waste, their diets and how fresh the manure is — that is, how far along it is in its decomposition process.

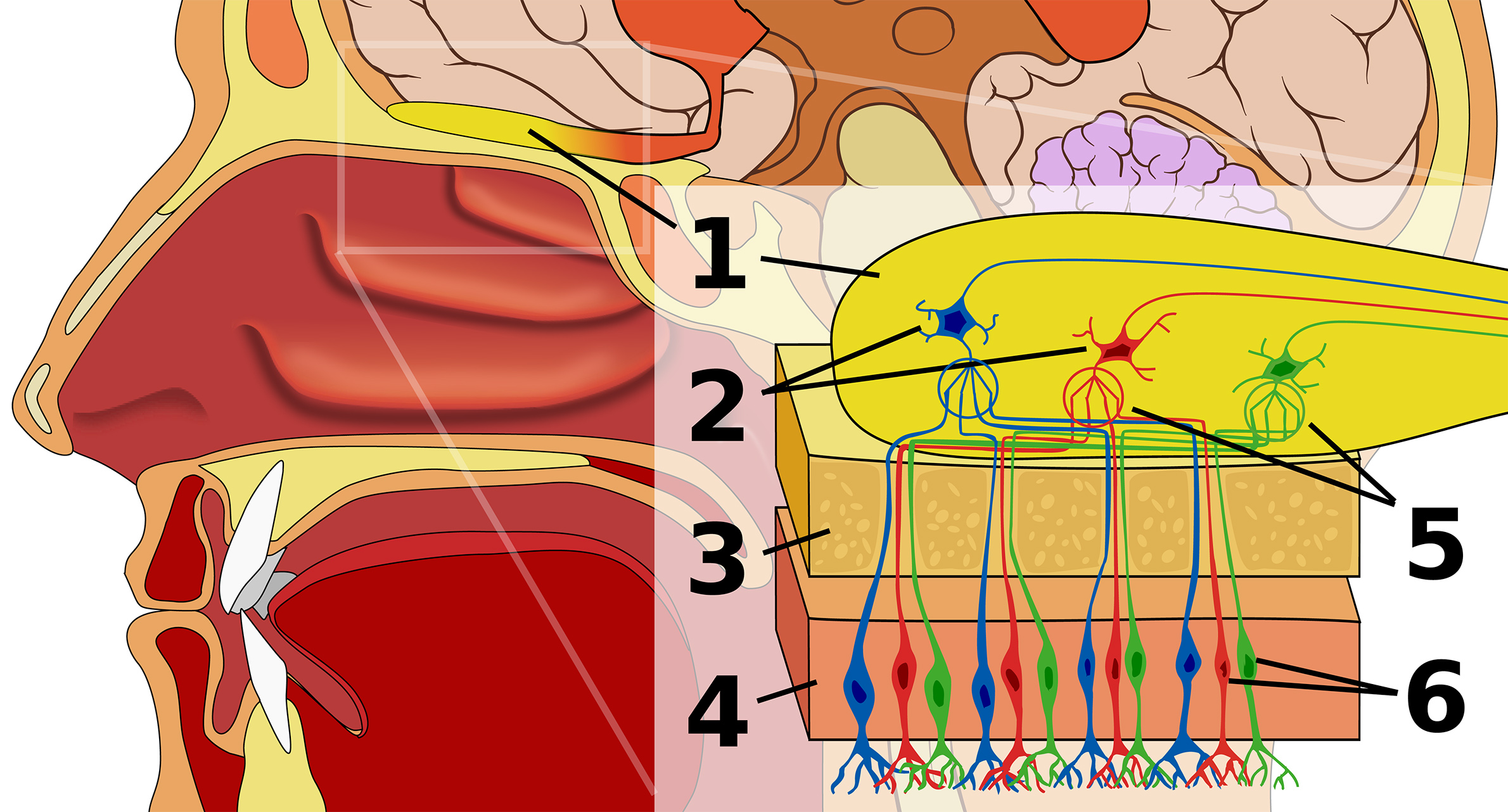

When odorants drift through the air and are inhaled by a person, they meet specialized cells at the back of the nose called olfactory receptors. These receptors relay information about the molecules they detect to specialized brain cells that process odor information and send it to other parts of the brain for processing that drives cognitive and emotional responses. It's this final step that helps an individual recognize and react to an odor. The experience of odor is thus highly individualized, dependent as it is on the wide diversity in both human bodies and experiences.

To further complicate matters, the experience of an odor also depends on the concentration and persistence in the environment of the molecules that cause it. Further, some odorous compounds also affect other parts of the body, such as eyes and the respiratory system. It all can make studying livestock odors and their potential impact on people quite challenging.

"It all ties back to our experiences and our histories," Cortus said. "My first experience with livestock odors was in swine production, so I've developed a bit more tolerance to those odors. But there are other smells that maybe annoy me more than others."

Despite these challenges, Cortus called the human nose "the gold standard" for studying odors. Indeed, scientists have devised multiple ways to train and "calibrate" noses for the purpose of studying specific odors.

How scientists study livestock odors

One of those scientists is Jacek Koziel, a professor of agricultural and biosystems engineering at Iowa State University. Koziel described two well-established approaches to scientific odor measurement.

The first approach employs a panel of well-trained analysts who calibrate their noses to specific smelly compounds. The most common compound for this test is n-Butanol, Koziel said, which is an alcohol that in gaseous form has a very standard and specific odor that some describe as similar to rancid butter.

"It's very recognizable at low concentrations," he said. "That's what we need because with livestock odors or any other odor we're looking at, we're often talking about low, very diluted concentrations of organic gases in the air."

Hydrogen sulfide is also sometimes used to calibrate noses due to its distinctive odor at very low levels.

The idea is that the sensitivity of an analyst's sense of smell can be determined with these standard, low-concentration odorants. Once researchers know how sensitive an analyst is to one of these standard smells, they can then "normalize," or calibrate their relative sensitivity to odor samples collected from the environment, say at various distances downwind from a manure storage structure.

The second approach, which Koziel uses more often, is to combine odor sensations aroused in a human nose with a chemical analysis of the compounds causing those odors. This type of research often involves releasing an air sample into a machine that can perform a chemical analysis while releasing part of that sample out of an opening through which a researcher can take a whiff.

"That can get really interesting," Koziel said. "Because it can get at the root cause of our reactions to compounds in the air. Is [a compound] obnoxious or pleasant?"

The technique can help researchers to precisely determine what compounds are responsible for unpleasant livestock odors.

"That's out of hundreds, if not thousands, of different compounds in the air," he said. "That kind of information is very useful for engineers to go after those compounds to try to eliminate them."

Eliminating or reducing odors is itself a whole field of research, and approaches can include physical and biochemical techniques. Physical odor management can take the form of something as simple as a cover for a manure storage structure or determining a distance at which manure odors dissipate below a certain threshold. Biochemical techniques range from chemically neutralizing odors to harnessing bacteria to digest manure into more useful (and less smelly) products.

Just how well these various techniques work is a matter of ongoing study, and also gets to the crux of a debate over how Wisconsin regulates where large livestock farms can go.

How odors help dictate where large farms can be located

In 2004, Wisconsin passed a law that sets the rules local governments must follow if they choose to regulate where new or expanding large livestock facilities can be located. Known as Wisconsin's livestock facility siting law, or ATCP 51, the statute defines a scoring process that attempts to ascertain the impact on neighbors of odors from barns and manure storages.

Odor scores depend on several variables, including distance to neighbors, predominant wind directions, type of livestock and facility, and odor mitigation strategies. Each variable is assigned a range of scores that directly relate to odor measurement and mitigation research from when the scoresheet was developed in the mid 2000s.

But this "odor management scoresheet," as it's known, is now on the chopping block. The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, which reviews the science that informs its livestock siting rules every four years, has determined that some of the assumptions involved in the scoresheet are incorrect or outdated.

The agency is also contending with a recent dearth of research into livestock odors, as public funding priorities have shifted in other directions in the last decade.

"At the time this rule was being developed in the mid 2000s, odor was one of these issues around livestock operations … that a lot of people were trying to address," said Chris Clayton. He manages the revision process for DATCP's livestock siting rules.

"There was quite a bit of research funding at the time, leading to a number of studies showing how much odor and air emissions were coming from manure storage structures, from hog barns, from dairy barns and animal lots, and so forth," Clayton said. "There were actual numbers being generated by research, and a lot of research that was specific to the upper Midwest."

DATCP incorporated some of that research into its scoresheet protocol, which is a unique approach to odor management in the United States, Clayton said. However, since much of that research has since ceased, the impact of some newer odor management technologies that livestock operators have proposed remain unvetted in the scientific community. That makes it difficult to incorporate those strategies into the scoresheet.

At the same time, Clayton said some odor mitigation strategies that have helped facilities reach passing odor scores have been found to be less effective than initial research indicated. One example is the use of anaerobic digesters, which employ bacteria to process manure into less stinky byproducts.

DATCP is looking to replace its scoresheet with a new odor management approach: dramatically increased mandatory distances between manure and livestock structures and property lines. Called setbacks, these distances could be reduced if a livestock facility uses any of several odor management strategies that remain scientifically supported, Clayton said.

Still, DATCP's new direction has raised concerns among farming groups who say the proposed setbacks could effectively halt growth in the state's livestock industries.

"I think it would have a chilling effect on people wanting to expand in the state and certainly on people who want to move and expand into the state," said John Holevoet, director of government affairs for the Wisconsin Dairy Business Association, in a Sept. 18, 2019 interview on Wisconsin Public Radio's Central Time.

The Dairy Business Association is a trade group based in Green Bay that represents the dairy industry, a sector in flux in Wisconsin as farms close in record numbers while the number of dairy CAFOs steadily increases.

The proposed change has also sparked a debate over the best science-based approach to managing livestock odors and whether mandatory setbacks would actually be a better alternative to the scoresheet.

"One of our concerns is maybe we haven't properly tested those proposed setbacks," Holevoet said.

A different formula for addressing odor

DATCP's Chris Clayton said the setback proposal is based on a rigorous research-based formula first developed in the early 2000s by researchers in Minnesota. It's called OFFSET, or the odor from feedlots setback estimation tool. The scientific findings underpinning this formula were the result of four years of field-based and laboratory study of the types Iowa State engineering researcher Jacek Koziel described.

OFFSET incorporates many of the same variables as Wisconsin's odor scoresheet. However, rather than assigning a pass/fail score to a facility, OFFSET predicts how far away a specific type of livestock barn or manure storage structure would need to be from a neighbor to reduce odors to an "annoyance-free" level most or all of the time.

While the research behind OFFSET is similar to what underpins the state's odor scoresheet, Clayton said the setback-focused formula would be simpler, sounder and more transparent.

"The new system I think would be easier to understand for everyone," he said. "The odor standard right now is honestly a model that very few people understand how to use … it's a bit of a black box."

The scoresheet is so befuddling, Clayton posited, that most local governments and operators applying for approval don't understand what goes into a score. He said that most applicants turn to a small pool of contractors in the state who know how to use the scoresheet.

DATCP's proposed rule revisions were the subject of 12 public hearings across the state and testimony from hundreds of stakeholders on both sides of the issue. Ultimately, the governor and state Legislature will decide whether and how Wisconsin will alter its management of livestock odors.

What makes a good neighbor?

Changes to Wisconsin's CAFO regulations will be moot for large livestock facilities already in operation or formally proposed, such as the hog facility planned near Trade Lake. That's because no matter what state leaders decide, any revised rules would only apply to facilities proposed after they take effect.

Russ Hanson and like-minded neighbors also won't get relief from a CAFO moratorium Burnett County passed during the summer of 2019. It also only applies to new proposals, and the operators of the proposed hog facility there entered their application days before the moratorium took effect.

All of that has Hanson and others wondering: If this colossal hog operation comes to fruition, how long would they stick around?

"Real estate agents are hearing from a lot of people like me who want to get out ahead of [the proposed hog farm]," Hanson said. "Because otherwise you're stuck with a situation like my in-laws."

At the same time, the would-be operators of the CAFO say that residents like Hanson are making hasty judgments that don't reflect how the owners plan to operate their business.

"To be honest with you, they all have a preconceived idea [that] they don't want it," said Jeff Sauer on Here & Now. Sauer is a consultant for Suidae Health and Production, the Iowa-based company behind the proposed operation. "We want to be a good neighbor, good to the community and good for the people in general. Unfortunately, it was not received that way," he said.

But the fact that Sauer is the only public face of an otherwise unfamiliar company with no other ties to the community doesn't sit well with many of the CAFO's potential neighbors, including Ramona Moody. She lives directly adjacent to the field where the operation is planned, and heads the anti-CAFO group Know CAFOs.

"They're an LLC," Moody said on Here & Now. "They can pick up and they can move on when the moment is right for them, leaving us with what's left behind: the clean-up."

In the end, this dispute in Trade Lake is instructive of a larger statewide tension between large livestock farms and their neighbors — one in which odors are a distinct part of a greater conflict over individuals' rights to use their land, whether for business or pleasure.

"I agree people should be able to do what they want on their own property," said Moody. "But it shouldn't affect your neighbor."