New Rules Highlight How Little Wisconsin Knows About Its CWD Problem

Wisconsin environmental regulators announced in August 2018 that they will take new steps to track and try to curb the spread of chronic wasting disease among the state's deer population. The state Department of Natural Resources will require deer farms to strengthen their fencing and restrict hunters' ability to move deer carcasses from zones where wild deer have previously tested positive for the always-fatal disease. These moves follow more than a decade of Native American tribes, hunters, farmers, and conservationists calling for tougher measures and more extensive testing to curb the spread of CWD.

Throughout that time, Wisconsinites have really never had a clear statewide picture of how prevalent the disease really is, and scientists are still working to understand how it spreads, with transmission possible via plants, soil, and the sharing of food and mineral licks. While CWD has not jumped to humans, concern is mounting that it will, with devastating consequences. Malformed proteins called prions cause this disease and others of its type, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy, also called "mad cow disease," can ravage the human central nervous system with fatal results.

In an Aug. 10, 2018 interview with Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now, Wisconsin Wildlife Federation executive director and former DNR secretary George Meyer called the new rules "a major step forward."

CWD first appeared Wisconsin deer around the turn of the century, and while hunters and regulators generally recognize that it's spreading, the state is testing far fewer deer than it did initially. In 2002, the Wisconsin DNR analyzed samples from more than 40,000 deer, reflecting an early period of heightened caution after the early tests yielded positive results. But in every year since 2009, the number of deer tested has never gone above 10,000, though that annual figure picked up to 9,889 in 2017, according to DNR data.

What's more, annual testing efforts rotate geographically to different hotspots across the state, so one year's data is not directly comparable to the another's.

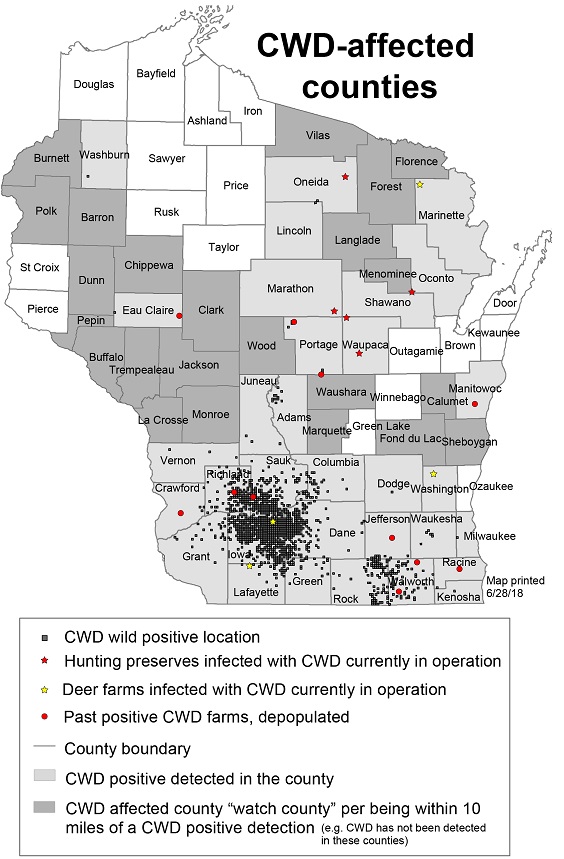

In any given gun deer season, hunters are shooting whitetails all over Wisconsin, but DNR data indicates that the state consistently tests orders of magnitude fewer deer from northern and central areas of Wisconsin than it does from its southern stretches. That difference is in part because CWD has done the most damage in southern Wisconsin, but at the same time, it's still popping up farther north as well. There's hardly a county in the state that doesn't at least border a county where CWD has been found.

County-by-county, the DNR tests at least one deer from each of the state's 72 counties in most years, but sometimes there's fewer than 10 tests in a given county, and sometimes there is only one. Even with year-to-year and geographic testing inconsistencies, the number of deer testing positive climbed significantly from 2006 to 2012, and has continued to exceed the 2002 numbers.

There's no statewide requirement for hunters to submit their deer for CWD testing, even in areas where the DNR knows the disease has infected deer. The state has at times offered financial incentives and set up infrastructure to try and encourage sampling, but not all hunters are interested. Sampling properly for CWD requires tissue from the head and neck, which generally means decapitating a deer carcass and rooting around for chunks of brainstem. Otherwise, hunters can just cut the head off and submit it to the state, which can require freezing or refrigeration for a few days if one can't drop it off right away.

As for the role of captive deer in the spread of CWD, deer farm operators have long contended that they're unfairly blamed, and have complained that the fencing regulations could force them to spend millions of dollars.

Meyer told Here & Now he thinks most farmers will opt for electric fences because that is the least expensive option under the new regulations.

Several counties in northern and western Wisconsin have had captive deer test positive for CWD before wild hunted ones. These findings raise the possibility that deer farms could provide jumping-off points for CWD in areas where it hasn't yet taken root among the wild deer herd. However, deer farmers with CWD-afflicted animals can receive indemnity payments from the state.

Meyer pointed out that there have been 10 new outbreaks of CWD on deer farms, and said he favors tougher rules still for hunters as well as farms, including restrictions on setting out food as bait for wild deer.

"When you bring these animals together over feed, you get saliva and other ways of passing the prions that cause chronic wasting disease," Meyer said.