This Milwaukee Restaurant Asks Patrons To Pay What They Can

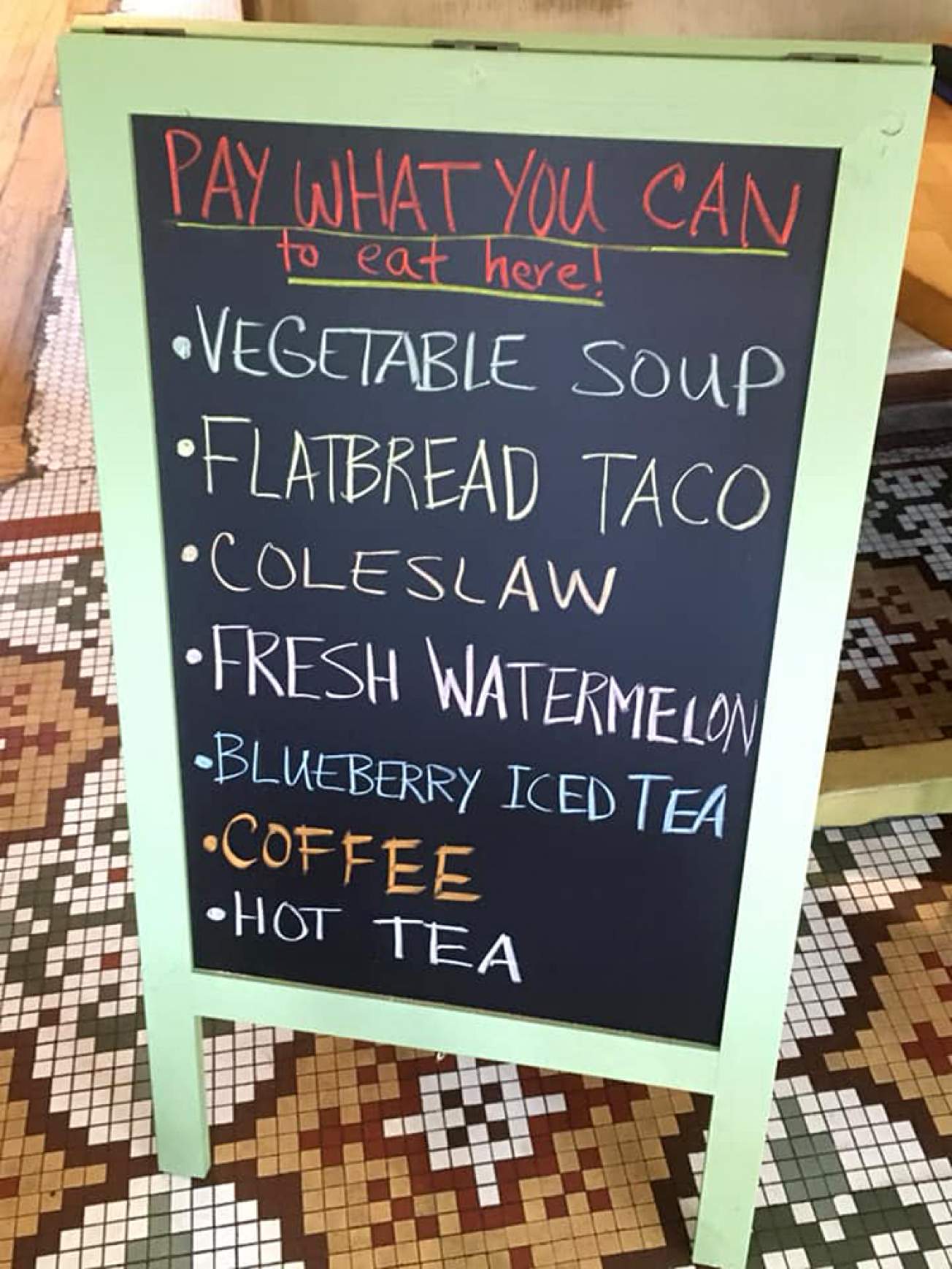

From the outside, Tricklebee Café at 4424 West North Avenue in Milwaukee's Sherman Park looks like any other restaurant. An A-frame chalkboard outside announces the special of the day: winter grain stew with a side of Hasselback potatoes and a radish, apple and roasted sprout salad. For dessert, there's lemon-lime tart with an oat crust.

Upon entry, however, it becomes clear that this café is different. Today's special is the menu, and there are no indications of how much lunch costs. Instead of a cash register, there is a plastic donation bucket seated on top of a wooden pulpit that wears a sign reading, "Order here."

The Tricklebee Café is a pay-what-you-can restaurant, and absolutely anyone is welcome to a healthy, delicious meal, regardless of his or her ability to pay for it. Even those with no money are encouraged to come and eat, and are asked only to stick around after lunch to help wipe tables or clean up dishes.

The inspiration for the nonprofit Tricklebee Café began about four years ago when Christie Melby-Gibbons was living and working as a Moravian pastor in Downey, California, southeast of Los Angeles. At the time, her church was struggling to find food donations for its community meals. After learning that nearly one-third of all available food goes to waste in America, and much of it before it even reaches consumers, Melby-Gibbons began asking local grocery stores to donate food items that has passed their "sell-by" dates (sell-by dates are different than expiration dates in that they are meant to indicate peak freshness). Soon, Melby-Gibbons was picking up two carloads of food every week.

It was during this time that Melby-Gibbons found what she says is her real calling in life. "We need to get over this idea that healthy eating is only for certain people," she said. "There should be access to affordable, healthy food every day for everyone on the planet."

While researching how to expand her food program, Melby-Gibbons came across One World Everybody Eats, a nonprofit organization that works to alleviate food insecurity and strengthen communities through the pay-what-you-can restaurant model. According to Feeding America, the nation's leading hunger relief organization, nearly one in eight Americans face food insecurity, which means they are not getting the recommended nutrition to maintain health. To address this issue, One World Everybody Eats supports new and established cafés through consultation and networking.

"If we could eliminate waste in restaurants, agriculture, grocery stores, and wherever food is served or harvested, I believe we would have enough food to feed the world," said One World Everybody Eats founder Denise Cerreta in an interview with More Magazine.

Cerreta and One World Everybody Eats developed a pay-what-you-can model in which at least 60% of restaurant customers pay market price (typically between $5 to $8) for their meal, and 20% pay above market price in order help cover costs for the 20% who pay below or nothing at all.

Melby-Gibbons attended a few One World Everybody Eats summits and felt inspired by the stories of the café owners and volunteers who serve nearly 4,000 meals a day. Soon after, Melby-Gibbons and her husband, David, decided to return to the Midwest, where she grew up, to start her own pay-what-you-can café.

After learning of high levels of food insecurity in Milwaukee, Melby-Gibbons and her husband decided to open a café in Sherman Park, a neighborhood that is emerging from a history of violence and disrepair by building a more diverse and secure community. "We looked for an area that was neglected," she said. "Then we bought a house in the neighborhood. We thought, OK, we are going to live where we do this."

While one in ten Wisconsinites are food insecure, the highest rates for the state — 22% — are in Milwaukee County, according to Feeding Wisconsin, the statewide association of Feeding America. When rent or medical bills need to be paid, corners get cut — usually starting with meals. Families facing food insecurity are prone to further health risks; hunger and health are intimately connected.

Melby-Gibbons sees Tricklebee fulfilling three central needs for residents of Sherman Park. Tricklebee serves as a spot for community interaction. It's a safe, warm and peaceful place for community members just to be neighbors. The café's large dining tables encourage barriers to crumble as strangers dine together. In this way, the café also provides spiritual nourishment for its customers.

"The most consistent feedback I hear is, 'What a joyful place,'" said Melby-Gibbons. "The space lifts you up."

Just as often, it is the need for physical nourishment that brings in food-insecure residents who are struggling to find healthy, fresh food or produce in their neighborhood.

Hunger Task Force, a leading anti-hunger nonprofit in Milwaukee, identified Sherman Park as a food desert — one of five neighborhoods in the city without access to a nearby grocery store. Slightly over half of Sherman Park's residents are low income, according to a Milwaukee neighborhood survey from Urban Anthropology, and likely face transportation challenges that make travel to distant stores a difficult prospect.

The name, Tricklebee, was inspired by the saying, "the trick will be," since Melby-Gibbons knew from the start that the largest trick would be funding the café. However, about three years after opening, the café is still afloat, thanks largely to overwhelming community support. Food preparation, custodial and table waiting tasks are all handled by Melby-Gibbons, a few hired staff members, and a team of volunteers.

On this particular day, volunteers Neil Moss, Amy Matkey and Lakeya Yarbrough are assisted by Melby-Gibbons' husband, David, who helps out at the café whenever he can. Most of the volunteers began working at the café as a community service project; others hear about the café through word of mouth.

Every day, the menu at the café changes based on which food donations are available and which need to be used the fastest. Almost every ingredient on the menu is vegan friendly and gluten free, because working with mainly plant-based materials helps kitchen workers minimize instances of cross contamination while preparing food. A vegan menu also conforms to many dietary restrictions and ensures the food being served is low in unnecessary fats and salts.

Each recipe is created by Yatesha "Tesh" Price, Tricklebee's head cook. When the need arose in December 2018, Price agreed to be the interim cook "until they found the right person." It took only about two weeks for Melby-Gibbons to realize Price was exactly "the right person" they were looking for: She is a great cook, has the right creative energy and believes in the café's larger mission.

"I'll tell you how I come up with the menu, but only if you don't laugh," said Price with a grin. "It's based on the weather. I think of a menu that would make me feel comforted depending on the weather outside. … It's like [the TV show] Chopped, the vegan version!"

In forwarding her mission of food equity, Melby-Gibbons also focuses on educating Sherman Park residents on healthy food through free Healthy Choices workshops where community members can come and learn how to cook.

Knowing where to buy a product like kale is one thing, she said, but knowing what to do with it and how to prepare it is just as important. The café has also been providing youth opportunities to learn about food sustainability through a variety of internships where students can help in the gardens, in the kitchen, or with custodial tasks.

The pay-what-you-can philosophy works so well in action because it minimizes food waste while providing nutrition and education to communities in need. Melby-Gibbons and other pay-what-you-can owners/operators across America are at the forefront of imagining a more equitable food security future. While their menus might vary and their locations differ, these cafés share a core belief: Healthy, nutritious food should be affordable and available to all people.

Editor's note: This article was adapted after being originally published in the spring 2019 issue of Wisconsin People & Ideas, a publication of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters.

This report is the copyright © of its original publisher. It is reproduced with permission by WisContext, a service of PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio.