The Changing Faces Of Wisconsin's Foreign-Born Residents

Immigration is an engine of change that has shaped Wisconsin throughout its history, reflecting the broader story of newcomers building new communities around the United States. The arrival of people born in other countries has not been constant, though. While the number of foreign-born people living in Wisconsin is trending upwards in the 21st century, this trend is only an echo of the mass migration that defined the state's early decades.

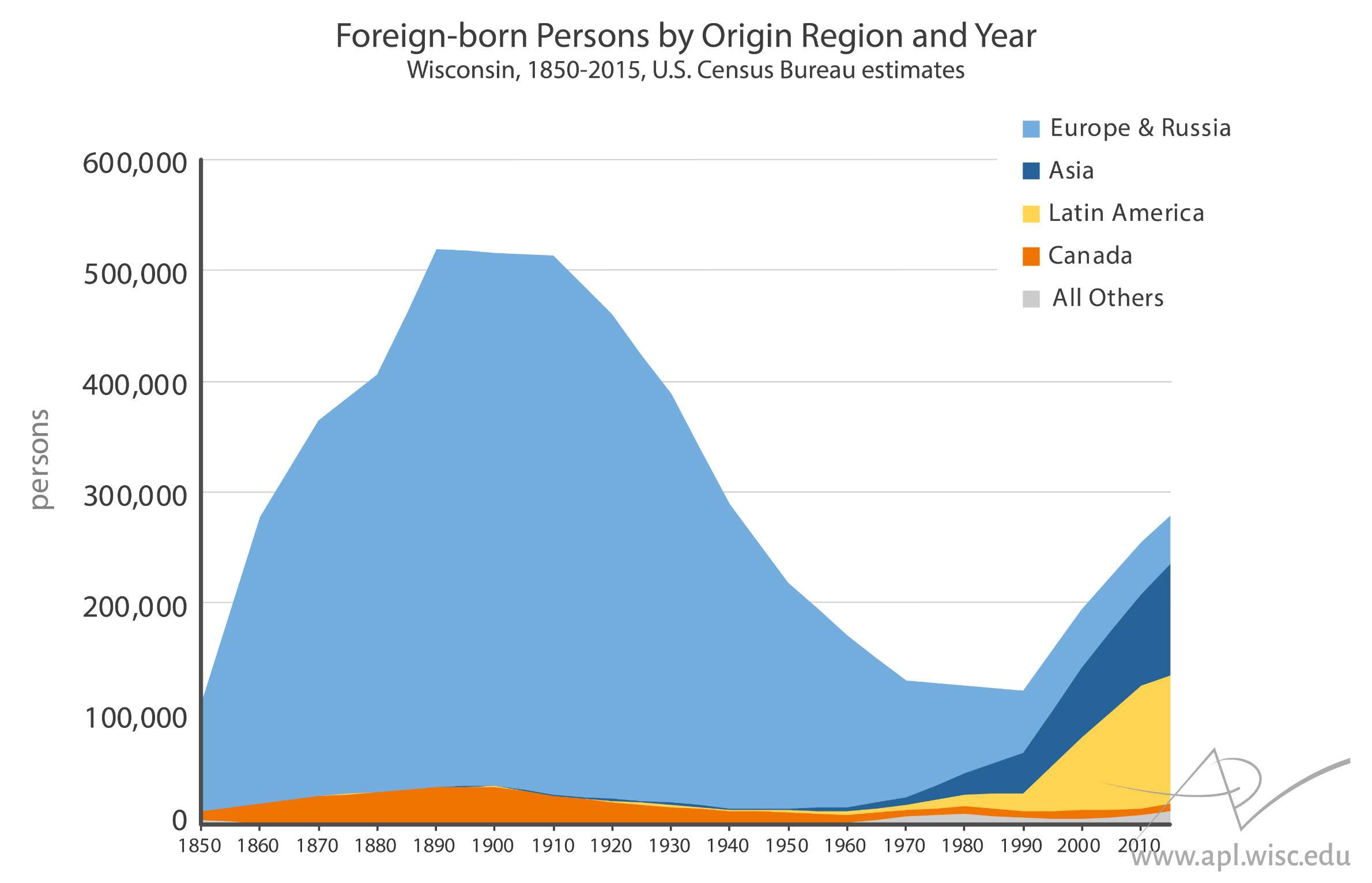

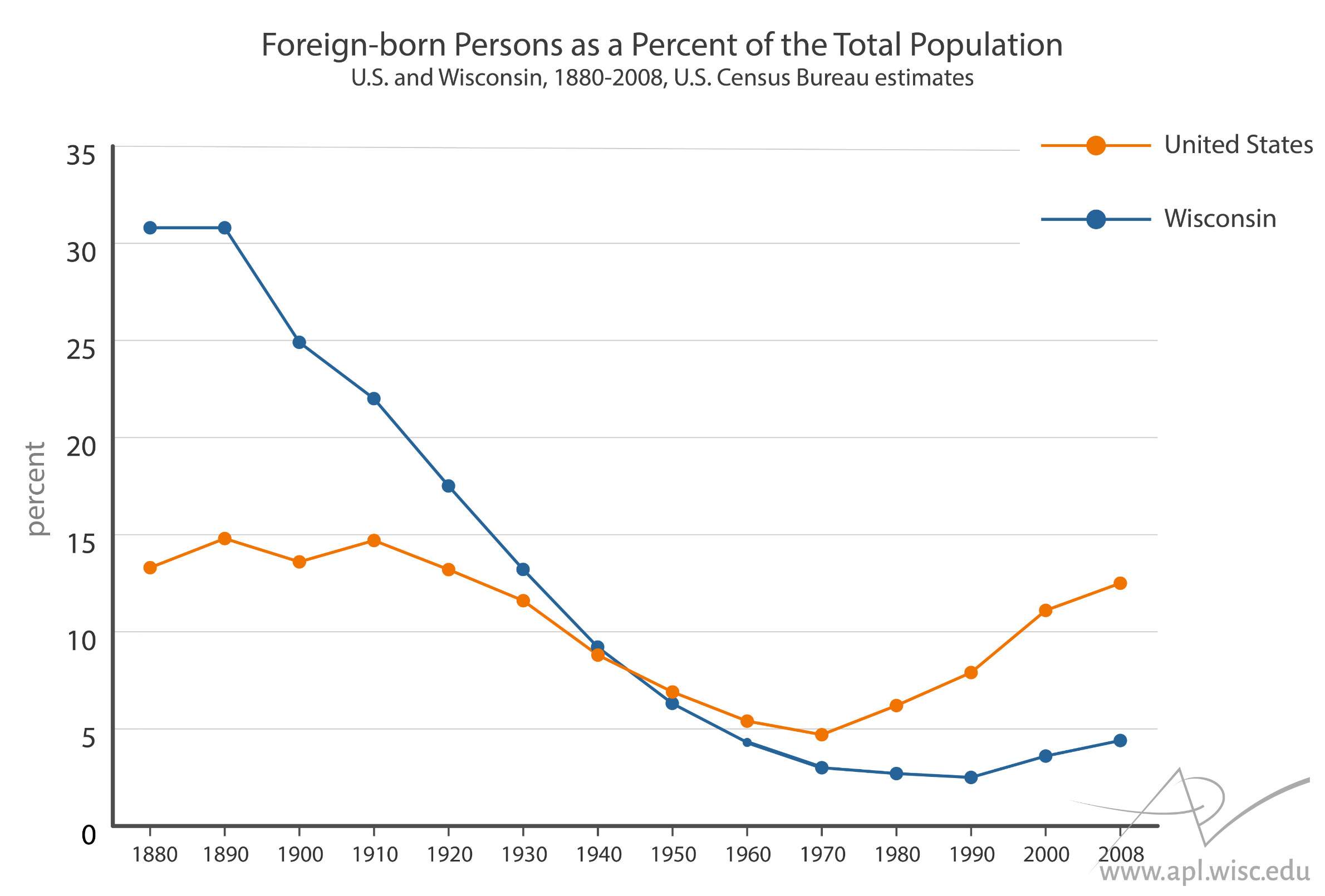

Since the early 1990s, Wisconsin's foreign-born population has increased by 130 percent. But the state's foreign-born population peaked a century earlier in 1890, when an estimated 519,200 persons born in other countries resided in the state, nearly double the number living in it in 2015. Even earlier in Wisconsin's history, just two years after the state's founding at the time of the 1850 U.S. Census, the foreign-born constituted well over a third of its total population. Today, they make up less than 5 percent.

Who are the foreign-born residents of Wisconsin? The term applies to anyone who was not born a U.S. citizen. It includes naturalized citizens, permanent residents with documentation (such as green card holders and refugees) temporary residents with visas, and people without legal authorization, a group the U.S. Census Bureau describes as "unauthorized migrants."

The changing nature of immigration to Wisconsin

The 21st century uptick in foreign-born persons living in Wisconsin is distinguished from historic immigration streams by the increasing diversity in region of birth. For nearly 150 years, the state's foreign-born population was dominated by people from Europe, particularly from places like Germany, Poland and Scandinavia. But the aging and eventual death of earlier waves of first-generation European immigrants, partnered with more recent growth in migration of people from Asia and Latin America, resulted in a dramatic decrease in the share of immigrants from European origins. Beginning after 1970, Wisconsin experienced an increase in foreign-born persons from Asia, followed by growth in persons from Latin America two decades later.

The "all other" category includes people born in Africa and Oceania, people born at sea and people with unknown national origins. Additionally, migrants from Greenland are included in Canada's counts. Though Native Americans born in the U.S. are native-born by definition, immigrants from Canada, Mexico, Central and South America may also have indigenous ancestry.

A large number of the early migrants to Wisconsin from Asia were Hmong, many of whom were born in Laos, displaced and ultimately resettled as refugees after the Vietnam War. In 2015, about 38 percent of all Asian Americans in Wisconsin were Hmong, although many Hmong Wisconsinites are the native-born children and grandchildren of refugees and not foreign born.

Immigration from Latin America has been shaped more directly by Wisconsin's economy.

In 1940, there were just 1,061 people from Central and South America permanently settled in Wisconsin, according to that year's census. These Latino immigrants were listed as "foreign-born whites." However, race is a fluid concept that is constantly changing as society does. Not surprisingly, the categories and definitions used to define race were very different on the 1940 Census. Although the census instructions in 1940 indicated that Mexicans were to be listed as whites, "unless definitely of Indian or other nonwhite race," there was no guidance for indicating the race of people originally from Central and South America.

It's likely there were more Latin American immigrants in Wisconsin who were not included in 1940 (and other censuses) because they were identified by the census taker as being categorized racially as Native American or black. Just after this census, starting in 1942, the Bracero Program brought thousands of foreign-born Latino workers to Wisconsin on temporary work permits. Though that government program ended in 1964, a demand for labor in agriculture and manufacturing continued, and with it a stream of migrants from Latin America.

Around 100,000 foreign-born Latinos lived in Wisconsin in 2015, a number that has been stable through the 2010s. This group is made up mostly of people born in Mexico, and are a mix of naturalized citizens and noncitizens. Wisconsin has also welcomed political asylum-seekers from Cuba, El Salvador, Colombia and Nicaragua. Some Latino immigrants arrive in Wisconsin directly from their origin countries, while others initially move to traditional destinations like Texas and California before coming to the state.

Wisconsin is also home to about 52,000 people of Puerto Rican descent. People born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens at birth, so though they generally identify as Latino, they are not counted as members of the foreign-born population.

Wisconsin's foreign-born compared to the U.S.

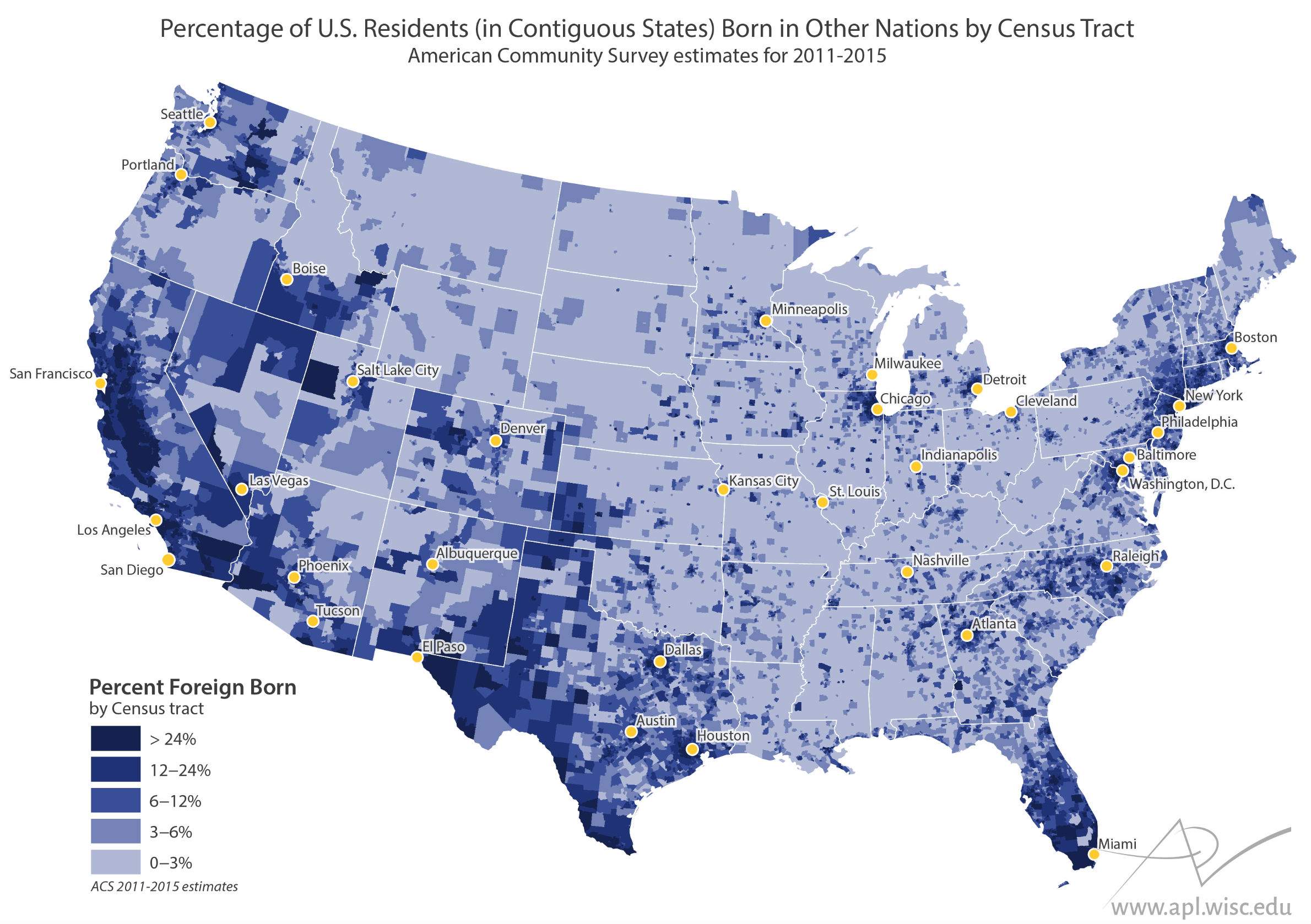

Despite increases in recent decades, the foreign-born population of Wisconsin remains small relative to other many other states and compared with the U.S. as a whole. With 4.8 percent of its population being foreign-born in 2015, Wisconsin was positioned 35th among the 50 states and District of Columbia.

Southwestern states like Texas have much larger relative proportions of foreign-born residents, for both citizens and noncitizens. These larger populations in other regions of the U.S. boost the numbers of foreign-born residents at the national level, where 21st century increases are considerably more dramatic.

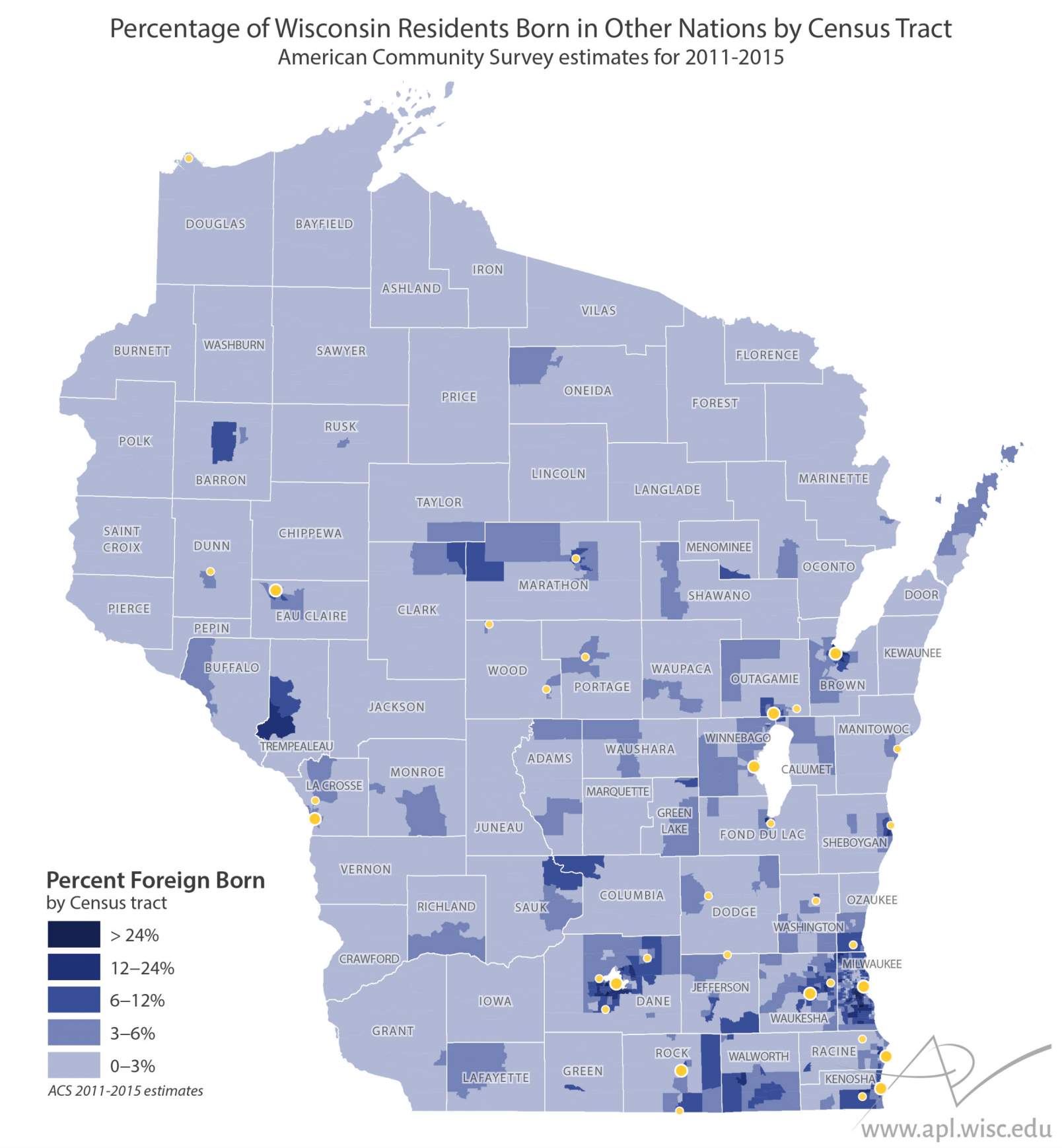

Where foreign-born people live in Wisconsin is not evenly distributed by location. Higher numbers are present in Wisconsin's cities, especially the urbanized southeastern area of the state. Some neighborhoods, mostly in Milwaukee County, might be considered immigrant enclaves with over 30 percent of their residents hailing from other nations. Overall, Wisconsin's cities host the largest share of foreign-born residents, a pattern consistent with other parts of the U.S. and broader migration trends around the world.

There are some rural areas of Wisconsin with a larger share of foreign-born residents. For example, rural Barron County hosts a large population of Somali refugees who started arriving there in the late 1990s, taking up work in the meat processing industry. Wausau and Marathon County are home to a concentration of Hmong immigrants. Meanwhile, Sauk and Columbia counties host a concentration of foreign-born workers in the service and travel industries centered in the Wisconsin Dells.

The community of Arcadia, a small city in Trempealeau County between Eau Claire and La Crosse, has seen a six-fold increase in immigrants from Mexico over the past 20 years. Many of these arrivals are farm and factory workers who bring their young families, helping boost declining school enrollment and inject new vitality into the local economy. However, rural immigrant enclaves can also be the source of friction, such as when Arcadia's mayor attracted national attention in 2006 by proclaiming English the official language of the town and calling for a crackdown on unauthorized immigration.

Unauthorized migrants in Wisconsin

Unauthorized migrants are noncitizens living in the United States without a current work or study visa, permanent resident status or other legal authorization. This group includes people who had visas that are now expired, as well as those who never had a visa. As for the term "undocumented," it is clouded by uncertainty about the future status of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals registrants, often termed "Dreamers." DACA was started in 2012 and was intended to provide a path to legal employment and residency for some migrants who arrived in the United States as children; unauthorized residents include DACA enrollees.

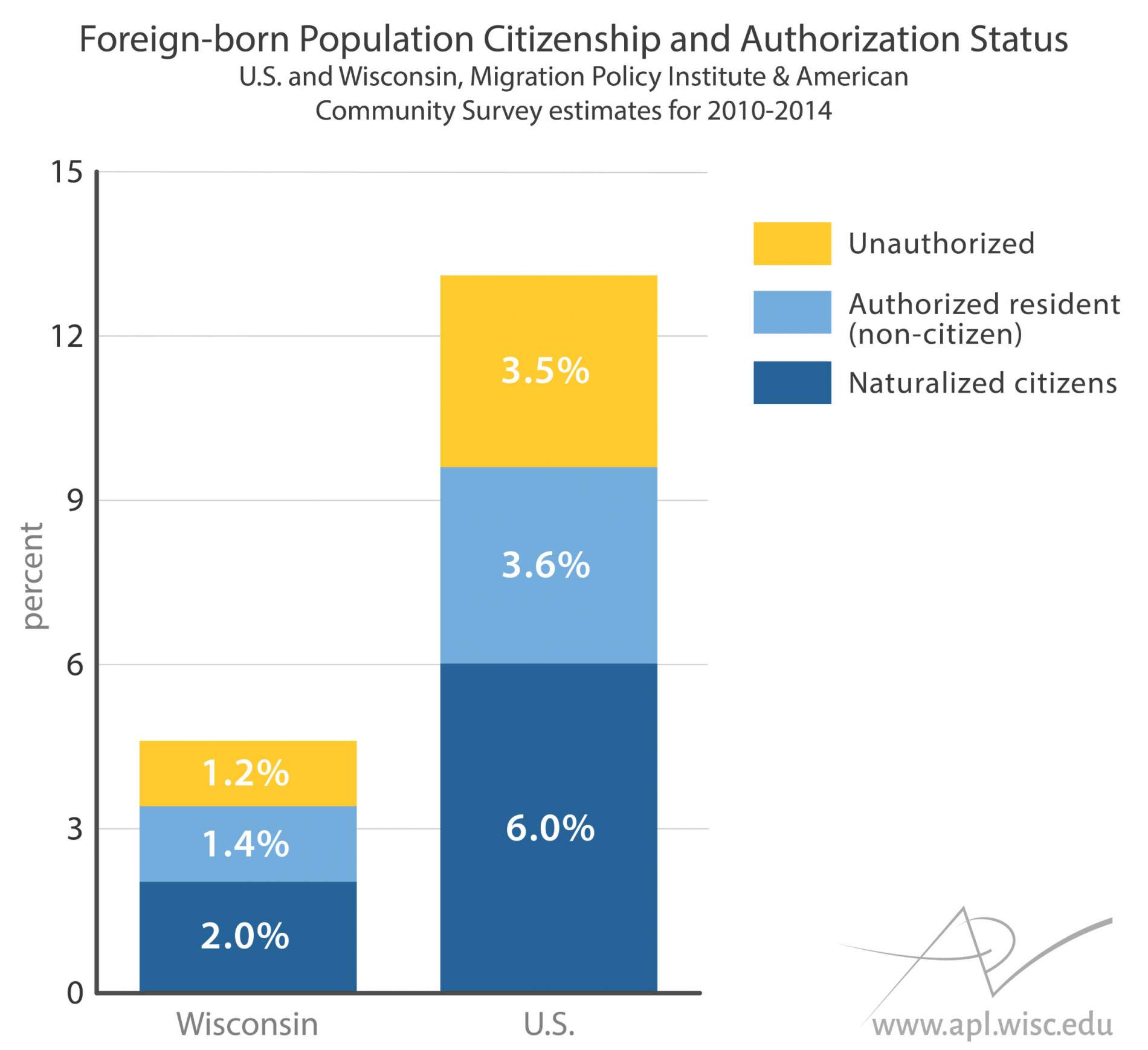

Lack of information makes the number and location unauthorized migrants difficult to characterize from a population-wide perspective. Their legal status and other social factors make them difficult to count using the formal surveys on which demographers usually rely. Although U.S. Census and American Community Survey data do not provide estimates of the unauthorized population, the Migration Policy Institute has created some estimates based on statistical models.

This nonpartisan, nonprofit organization estimated Wisconsin's 2010-14 unauthorized population to be around 71,000 persons, with 74 percent being Mexican by birth. Combined with estimates from the ACS, the Migration Policy Institute figures suggest that unauthorized migrants constituted about one fourth of the state's foreign-born population and just over 1 percent of the total population.

Immigration, employment and poverty

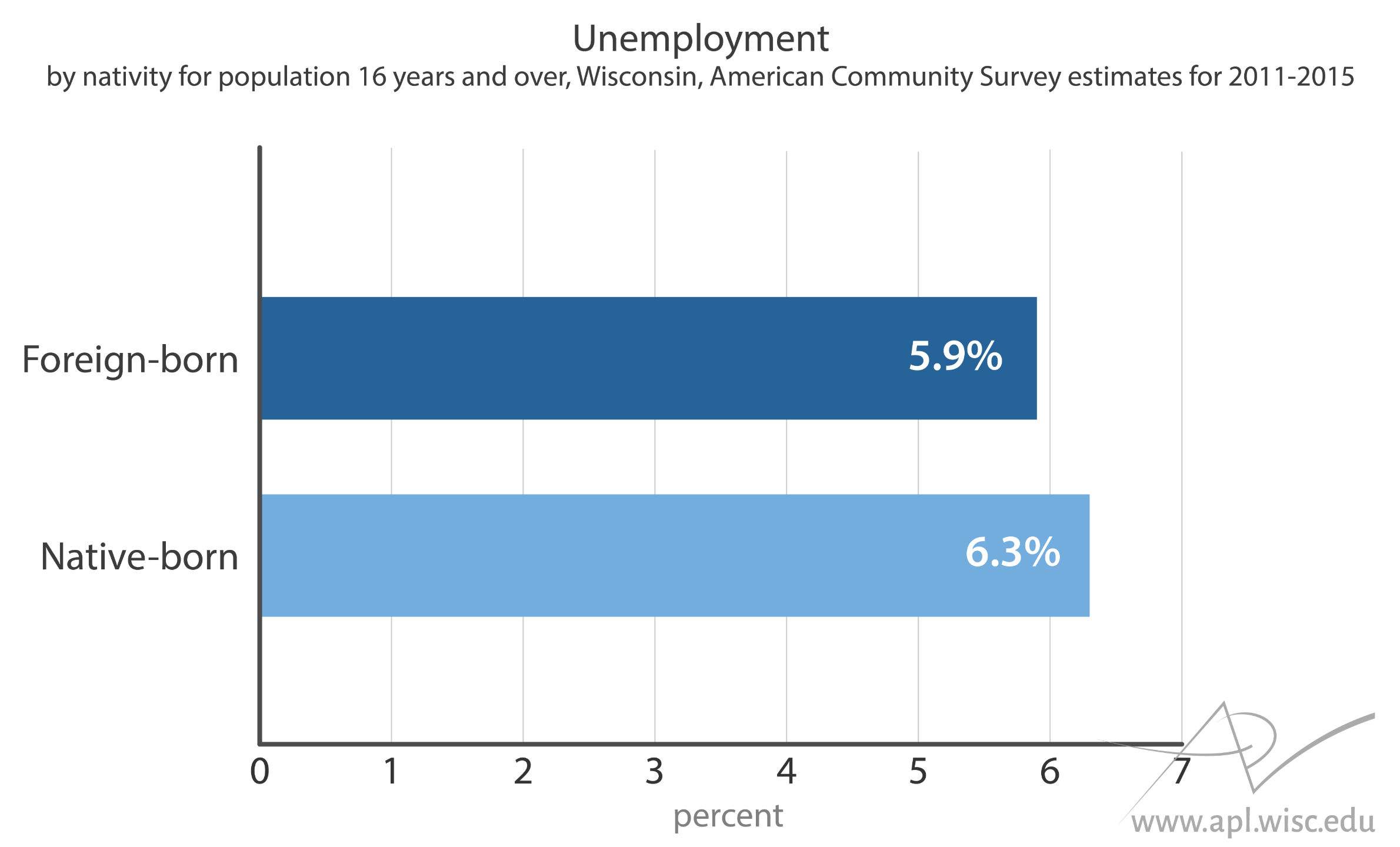

Labor force participation and unemployment rates provide another perspective on the role of foreign-born residents in Wisconsin's economy. The foreign-born population has approximately the same rates of labor force participation as native-born residents. Since most immigrants move for the purposes of finding employment, this is not a surprise.

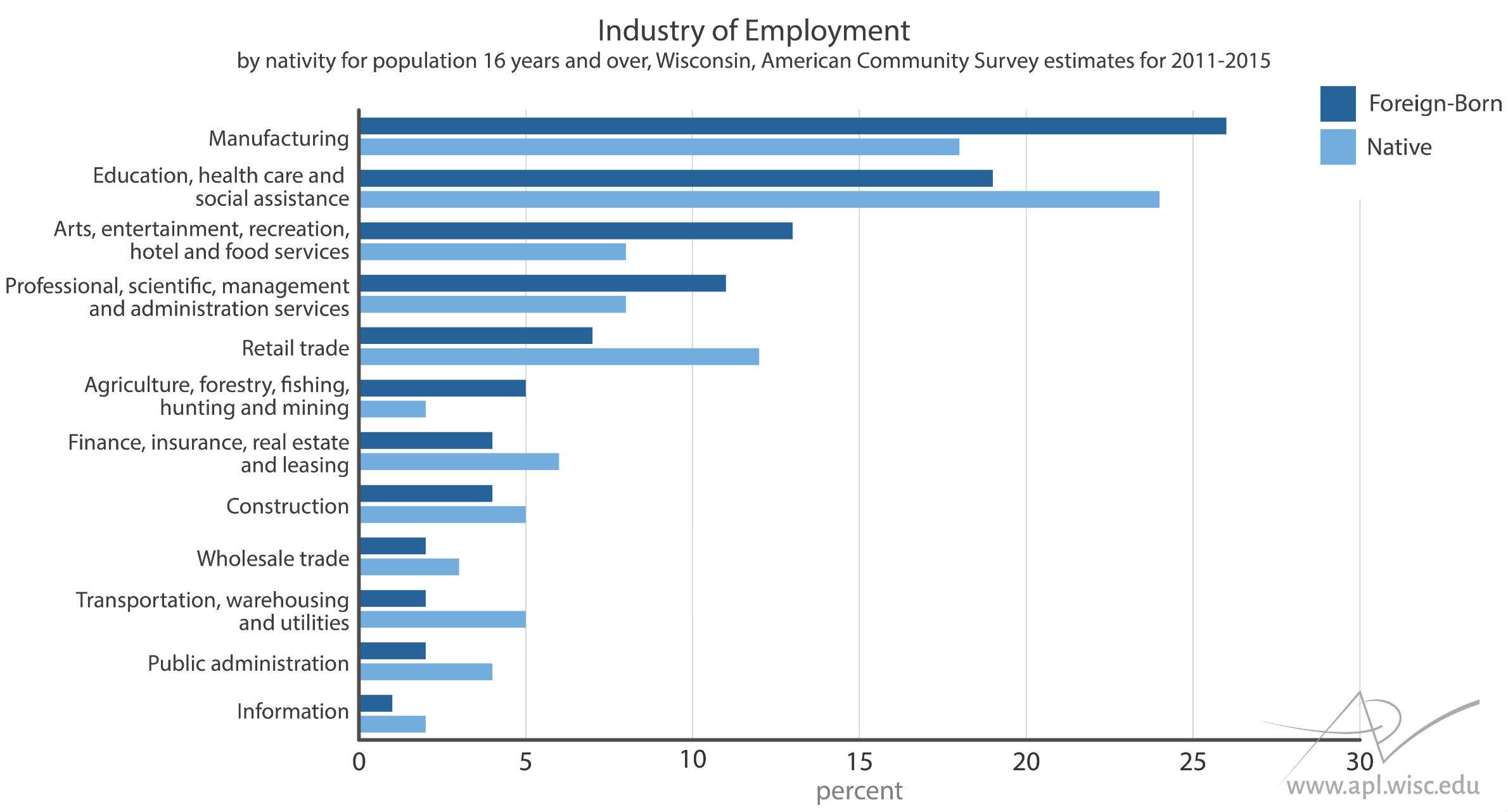

Also notable is the distribution of foreign-born workers across industries. Many immigrants work in manufacturing, including food manufacturing. One 2009 study by University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers estimated that immigrants comprised 40 percent of workers hired on dairy farms in the state. That rate of employment emphasizes the significant role immigrants play in the state's famed dairy industry.There is also a higher relative proportion of foreign-born residents working in service industries, a wide category which includes lab technicians, data-entry professionals, hotel and restaurant workers, landscapers, waste management workers, day care providers, nurses, auto repair technicians, hair stylists and many other occupations.

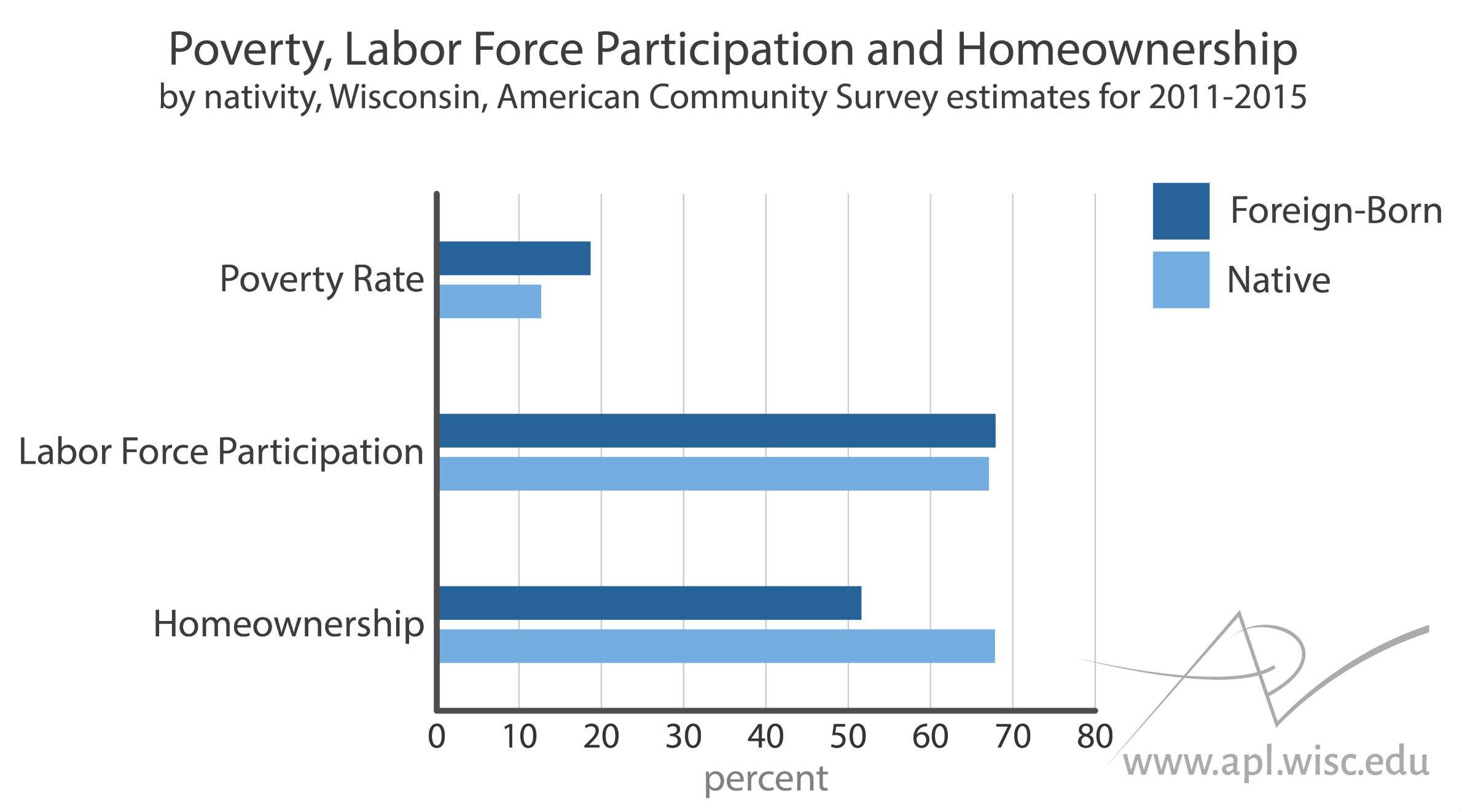

Despite high rates of labor force participation, much of the foreign-born population of Wisconsin experiences economic challenges. As a whole, foreign-born residents have higher rates of poverty and much lower rates of homeownership than the native-born population. Even though the average poverty rate is high for foreign-born Wisconsinites, not all are living in poverty.

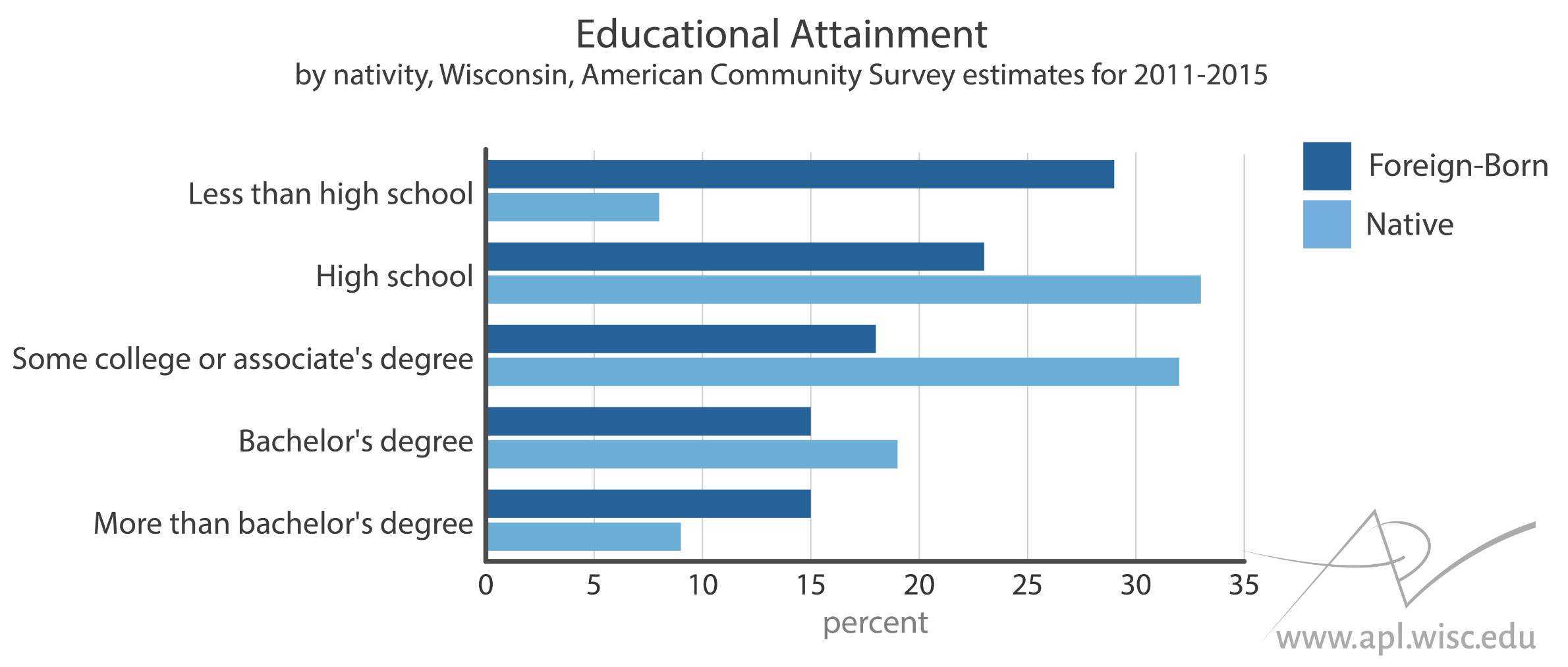

In fact, there is a lot of variation in terms of socioeconomic status within the foreign-born population. The level of education for the foreign born stands out at both ends.

In Wisconsin, there is a larger fraction of foreign-born residents who have not completed high school compared to their native-born peers. However, graduate-level education is also more common among the foreign born. These highly skilled people often come to Wisconsin to pursue advanced degrees and gain employment in professions like medicine, scientific research and graduate level education.

Public policy and future arrivals

In the future, shifts in U.S. immigration policy and enforcement efforts at federal and state levels may alter not only the number of foreign-born residents across Wisconsin, but the experiences of these people as well. As such, these changes are likely to have far-reaching social and economic effects across the state, for foreign- and native-born residents alike.