As Southeastern Wisconsin Grows, How Will Cities Source Water?

The city of Milwaukee sells a lot of water to other, smaller communities around southeastern Wisconsin — it's a typical practice of large public utilities in the state that draw water from Lake Michigan. However, the Milwaukee Water Works hasn't added a new client city since 2003, when the suburb of New Berlin came aboard its system. That will change in a few years, though, when the city of Waukesha's long-sought and controversial effort to tap the Great Lakes for drinking water becomes a reality.

Waukesha was long expected to go with the Oak Creek Water & Sewer Utility as its provider, so the announcement in October that it would instead contract with Milwaukee came as a surprise. The city's reasons are pretty simple: Milwaukee is closer to Waukesha than Oak Creek, so the cost of building new water mains and subsequently pumping water out to Waukesha will be lower.

Milwaukee will be sharing the cost of the construction, potentially investing as much as $18 million into the project. The city's water utility also benefits, because it will have a new revenue source and gets to spread its costs out among more customers.

Waukesha's successful bid to tap the Great Lakes reflects the complexity of governing access to what is increasingly one of the world's most coveted freshwater resources. It was the first major test of the Great Lakes Compact, an eight-state agreement that governs use of the lakes' water both inside and beyond the hydrologic area known as the Great Lakes Basin. The city of Waukesha is wholly outside this area, but is located within a county that straddles the basin's line, which means under the compact it's not entitled to source Great Lakes water but can seek access to it if its use meets certain conditions.

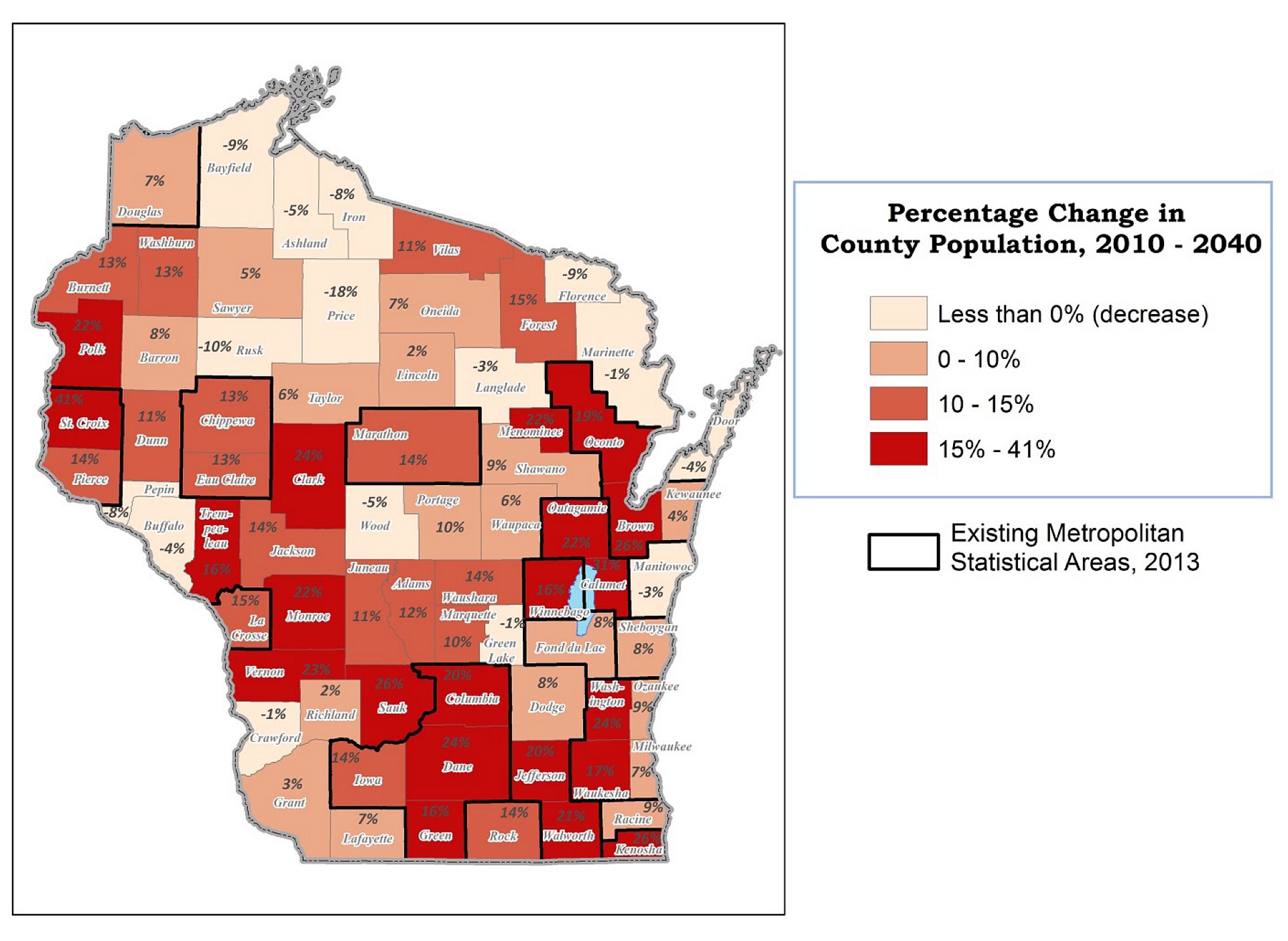

The project also reflects the challenges that southeastern Wisconsin, the state's most populous region, will face in supplying its population with clean drinking water over coming decades. The six large counties in the region — Milwaukee, Waukesha, Racine, Kenosha, Washington, and Ozaukee — are all expected to keep growing over the next couple of decades, according to projections from the University of Wisconsin Applied Population Laboratory. That growth isn't projected to be quite as explosive as that in St. Croix County (Twin Cities suburbs) or Dane County (Madison), but it does have significant implication for the region's surface and groundwater resources.

Regional groundwater resources under pressure

Waukesha turned to Lake Michigan in part because its drinking water has become increasingly tainted with radium. The radioactive mineral occurs naturally in deposits around the state, but Waukesha's water use made the contamination worse by drawing down groundwater at an aggressive rate, thereby increasing the concentration of the radium. The Milwaukee and Chicago metro areas have placed heavy demands on an aquifer system that underlies each.

A portion of the western Lake Michigan region's groundwater resources are in a relatively shallow sandstone aquifer that's hurting from more than a century of growing demand. The rest of this water is deeper underground, under a layer of shale, where it's harder for utilities to access and where sources of groundwater recharges, like rainwater and snowmelt, have a harder time permeating. In short, one aquifer is being depleted and another is slow to replenish itself.

"There is an effect due to pumping in northeastern Illinois, certainly… also we've seen that the center of pumping has migrated from located well to the east in Milwaukee County and now it's migrated toward the eastern part of Waukesha County," said Mike Hahn, executive director of the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission.

Given this issue, Hahn said it might arguably be better for the sustainability of water resources in the region if more communities tapped into the Great Lakes for drinking water, though he's cautious about taking that statement too far.

"Changing to a Lake Michigan supply can remove some of the pressure on the groundwater resource, most certainly, but we wouldn't say it's a blanket solution to the issue," he said.

Milwaukee itself is expected to be one of the slower-growing parts of the region, while nearby communities like Kenosha are likely to gain population much more dramatically. Jennifer Gonda, superintendent of the Milwaukee Water Works, doesn't necessarily expect population growth to be the biggest factor as she considers the region's water needs over the next several decades. Milwaukee's water usages is actually declining by about one percent per year because households and industries are becoming more efficient with water. Usage has declined nationally as well.

"It has to do with conservation, more water-efficient fixtures, changing practices in industries, the loss of water-intensive industries like tanneries and breweries that we used to have a lot more of in Milwaukee," Gonda said. "I don't really know that population is the driver of that. It's more changes in the technology and our industrial makeup."

When water utilities are building out new infrastructure, they generally have to think not just about immediate needs but also what might change over the long run. Say a utility is putting in a major new water main to serve a new subdivision a little ways outside of its usual service area. If even more development pops up around the route of that pipe, can it still carry enough water to serve those new customers? Can the anticipated new development over time make the upfront cost of putting in that new infrastructure worthwhile?

Selling water to Waukesha and its more than 70,000 residents will provide financial profit for Milwaukee in the long run, regardless of what else happens along the route the water travels. Still, Gonda is keeping the challenges and opportunities of other future developments in mind.

"We're always open to entertaining new customers and we certainly have the capacity to do that," Gonda said. "The infrastructure that we're putting in for Waukesha does strengthen our connections on the southwest side of the city, so that would be a consideration if a nearby community to southwest were to have interest in connecting to our system."

Elevation and energy

Another challenge that will arise if and when more inland customers tap into Lake Michigan is energy. As one moves west from its shoreline, elevation gradually increases. It's not a dramatic change, but enough to require a considerable amount of electrical power to pump millions of gallons of water uphill on a daily basis and maintain enough water pressure for customers turning on their taps. To send water to Waukesha, Milwaukee will have to help build not just pipes but also at least one pumping station. The elevation change also factors into the work Racine will have to do to provide water to Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer Foxconn's planned complex in Mount Pleasant, as Racine Water Utility manager Keith Haas explained in a recent WisContext report.

In that October 2017 report, Oak Creek water utility manager Mike Sullivan, apparently still expecting to win the Waukesha contract at the time, said he estimated that serving that city would cost Oak Creek an additional $2 million per year in energy costs alone.

Larger utilities including Milwaukee, Oak Creek and Racine have plenty of headroom to draw more Lake Michigan water without building new treatment plants or expanding their existing facilities. Milwaukee water chief Jennifer Gonda said the city is able to treat some 365 millions of gallons of water per day at its two drinking-water plants, but currently averages about 100 million gallons per day. That difference represents a lot of room for expansion, and communities in the area will gradually have to get more water from somewhere.

"It's not enough to meet future demand just through conservation," Hahn said "Our region is not expected to grow precipitously, but there will be some additional growth."