Trade War Aggravates Wisconsin's Slumping Agriculture Economy

A round of tariffs on steel and aluminum imports to the United States, set by President Donald Trump in March 2018, brought concerns about volatile trade relations and higher costs of production for the farm industry.

So what's been happening to Wisconsin farms since then?

Tariffs take effect

The 25 percent tariffs on aluminum and 10 percent tariffs on steel imports have been in effect since March 2018, but major trade partners including the European Union, Mexico and Canada were exempted until June 1. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced on May 31 that the United States would move forward with lifting the temporary tariff exemptions and impose metal duties for Canadian, Mexican and European Union goods after unsuccessful negotiations. The move was met with condemnation from world leaders

"These tariffs will harm industries and workers on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border and will disrupt supply chains that have made steel and aluminum from North America more competitive across the whole world," Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in a press conference.

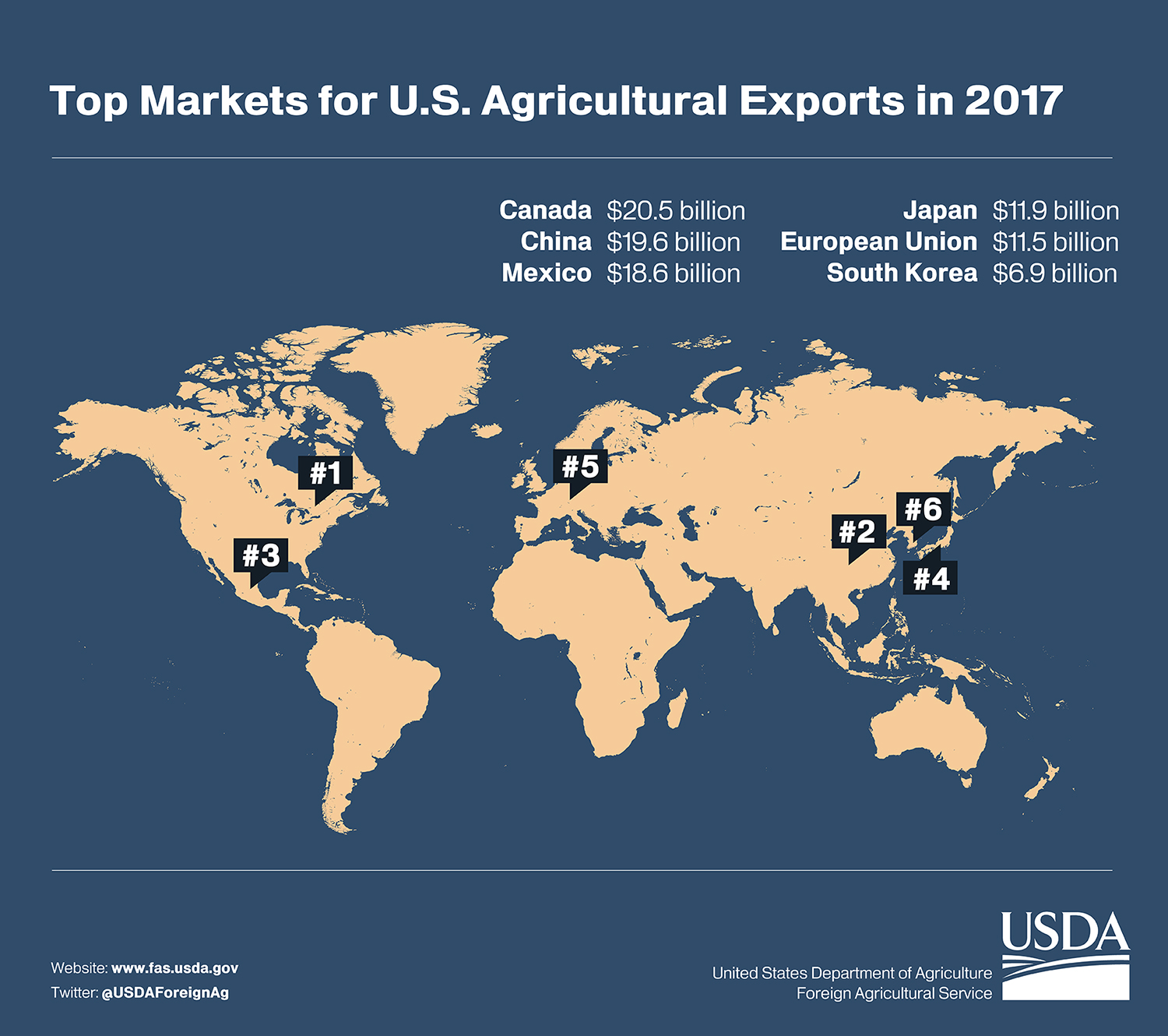

Mexico, Canada and the EU, major agricultural export markets for the U.S., immediately struck back with their own set of tariffs, targeting steel and aluminum and key commodities of American farm goods including cheese, corn, fruits and pork.

Wisconsin producers are seeing the effects of the trade wars. Experts agree the U.S.-China feud has the highest stakes. China is the nation's largest goods trading partner and made up $129.9 billion of U.S. exports in 2017, according to federal data. Their retaliatory tariffs target American agricultural commodities such as soybeans and dairy – goods Wisconsin is known for.

In July, CNN reported soybean prices hit a 10-year low at $8.55 per bushel — 13 percent lower than prices at the beginning of 2018. This was a week after the United States imposed a 25 percent tariff on $34 billion worth of Chinese exports to the United States, which China later matched with tariffs on soybeans.

In an interview, Kevin Bernhardt, University of Wisconsin–Platteville professor of agribusiness, said the soybean tariff hit especially hard.

"Agriculture prices live and die by exports. In all commodities, we're heavily dependent [on China], especially for soybeans," Bernhardt said.

The tip of the iceberg

Wisconsin producers are seeing the effects of the trade wars.

In October, the state's leading manufacturers and businesses met at a Waukesha town hall meeting, part of the Tariffs Hurt the Heartland nationwide grassroots campaign, to discuss the impact on Wisconsin’s economy.

Jim Holte, Wisconsin Farm Bureau president, said the Trump tariffs are "compounding the issues of global oversupply of food products" in nearly all of Wisconsin’s commodities like milk, grain, beans and oil seeds.

"Farmers are price takers not price makers," Holte said. "So while there is an active futures market out there, the opportunities to look forward and lock in a profitable price are very limited in nearly all of the major commodities."

A report by the Trade Partnership, an international trade and economic consulting firm, presented at the meeting, revealed tariffs cost Wisconsin businesses almost $95 million in August — 47 percent more than in August 2017.

"This is just the tip of the iceberg," said Carrie Clark Phillips, panelist and director of policy and partnerships for Farmers for Free Trade. She added Wisconsin businesses spent $20 million more that they never had to pay before as a result of the tariffs.

Agriculture downturn gets worse

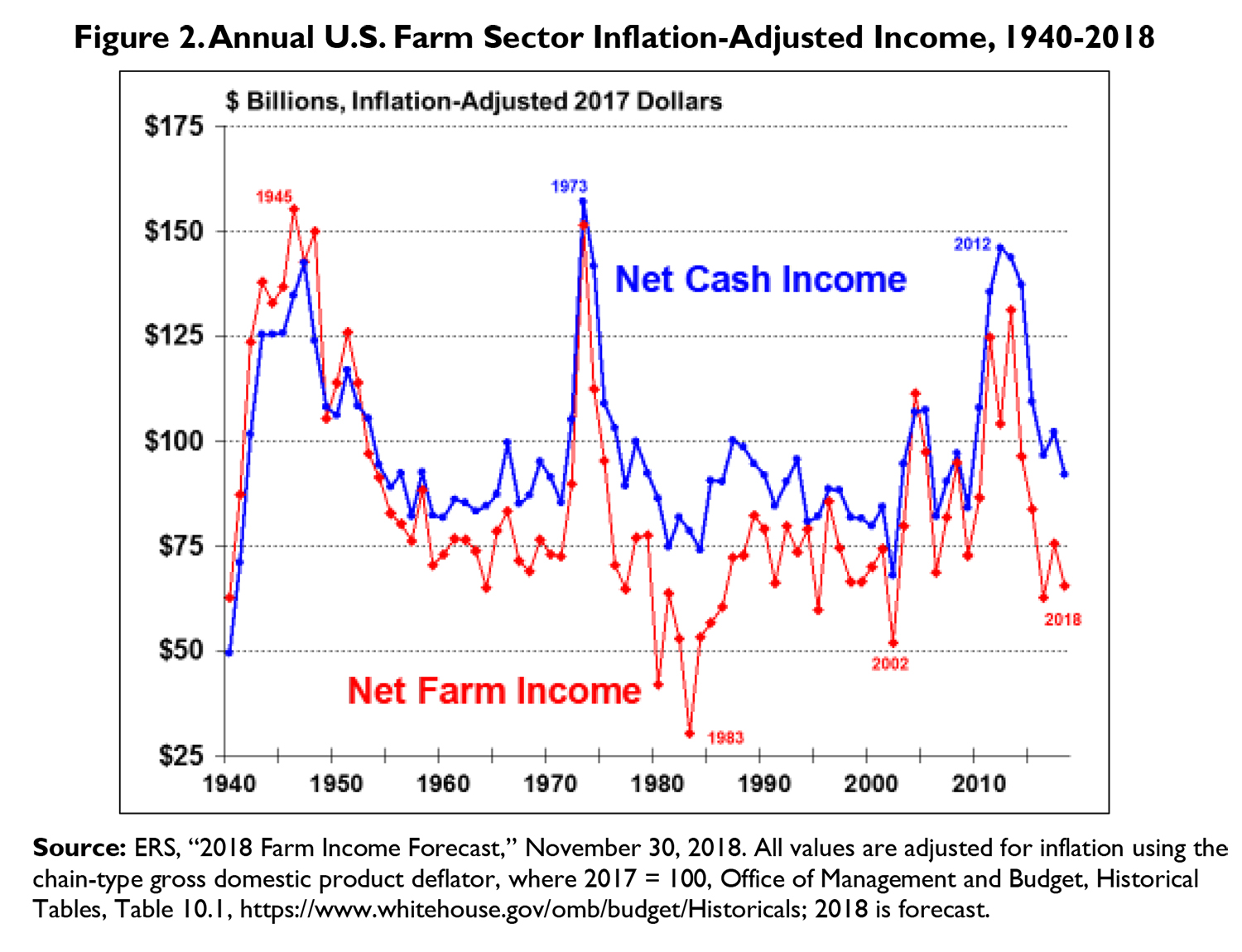

Agricultural experts agree the tariffs hurt farmers and prolonged downturn in the agricultural sector. From 2013 to 2017, U.S. net farm income fell 39 percent, from $123.8 billion to $75.4 billion.

In 2018, a Congressional Research Service report noted that the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service projected net farm income at $66.3 billion, a 12.1 percent decline from 2017.

"In May, we had $4.20 corn, we had $10.40 soybeans, and $16.60 milk — all those have come down since that time," UW–Platteville professor Kevin Bernhardt said in an interview in November 2018.

"I think they were all starting to slowly climb up to something that might've been better for farmers this year, and then the tariffs hit. So the tariffs took what little wind we were starting to get in the sails."

Oversupply of milk and persistently low commodity prices have hurt farmers, said Mark Stephenson, director of the Center for Dairy Profitability at UW-Madison. He said tariffs are a factor in the slow markets, but not the whole story.

"The biggest part of the story is probably just too much milk being produced for the what the market place actually wants and needs right now," Stephenson said. "But then into all the problems, in the mix, you throw tariffs against Mexico. Mexico is our biggest export customer, so when they put those tariffs on cheese, and cheese sales slowed down, that's not a good thing [for farmers]."

Now Wisconsin is left with a dairy industry that has a gas pedal with no brakes, said Kara O'Connor, government relations director at the Wisconsin Farmers Union, an advocacy group for family farmers and rural residents.

"We have technology that makes it easier to ramp up production faster, and we have federal policy that creates no disincentive for doing so," O'Connor said. "And for an individual farmer, the answer to every situation that you might encounter economically is to produce more."

Number of farms shrinking

Commodities tend to follow cycles of varying lengths of high and low prices, UW-Madison's Mark Stephenson said. Dairy farmers have become accustomed to these cycles in prices, and stock up on working capital to survive down periods, he said.

This time around, though, the market hasn't rebounded, driving farmers to take on loans to "borrow against their future" or go bankrupt, Stephenson said.

The number of dairy farms in Wisconsin sharply decreased in 2018, according to data from the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protections. Wisconsin had 8,801 licensed dairy producers at the beginning of the year and had lost 638 farms as of December.

Kara O'Connor of the Wisconsin Farmers Union said farm loss in the past three years has been "astounding." She regularly talks to farmers across Wisconsin, and has noticed even farms with multiple income streams from different commodities can’t turn to producing other goods because prices for everything are down.

"Every sector usually, even if milk prices are low, does well with animal sales and other things are low, but now it's just crickets everywhere," O'Connor said.

Bankruptcies level out

Recent data from the American Farm Bureau Federation reveal the national farm bankruptcy numbers are not quite as bad as 2017, but several regions, including the Midwest, continue to suffer high failure rates.

"Caseload statistics from the United States Courts indicate that for the 2018 fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30, there were 468 Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings, down 8 percent, or 40 filings, from the prior year," according to the Bureau. "Filings in fiscal year 2018 were down from prior-year levels but were approximately 25 percent higher than in 2014."

Although bankruptcies are down from 2017, the group, which represents farm and ranch families, notes the data "highlights the tough financial conditions across portions of rural America."

The Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings, known as "family farmer" or "family fisherman" bankruptcies, were higher than year-ago levels in the Northeast, Midwest and Rocky Mountain regions. And, of the 468 filings in fiscal year 2018, more than half came from districts highly concentrated in traditional row crop, livestock and dairy production, the bureau reported.

Kevin Bernhardt said there are still some producers who have figured out a way to keep costs low and break even — or make a profit off of the current prices. But he said farm casualties are an inevitable and unfortunate consequence of down periods.

Federal bailout not enough

Agricultural economists remain concerned about the farm industry, particularly the uncertainty of ongoing trade wars between the United States and China.

The Trump administration announced in August 2018 it would provide a $12 billion bailout for farmers affected by the tariffs. Farmers and others say that is not enough.

"We've estimated that it's probably between 50 cents at the minimum to something like a dollar per hundredweight of milk that prices were impacted because of the trade negotiations," Stephenson said. "The farmers got a [bailout] payment that's going to be equivalent to about 6 cents. That’s not much."

The National Milk Producers Federation wrote to Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue asking for more federal compensation to mitigate dairy farm losses from the tariffs, which are projected to easily exceed $1 billion in 2018.

Kevin Bernhardt said the tariffs could damage farmers' trade relationships, and declining profitability could disrupt the generational transfer of farms.

Kara O’Connor said farmers feel fear and isolation as they watch their neighbors close down one by one.

"Nobody that I've talked to could remember a situation with that ever happening. It’s completely unprecedented where people felt at risk at being terminated, not because of poor quality or violation on their part but simply because their product isn't wanted," O'Connor said. “So when you go forward first of all, not making any money and second of all thinking, 'I could lose my farm at any moment,' that's a terrifying way to live."

Said Mark Stephenson: "This trade war could be prolonged, and I don't know if you declare a winner to be the person who comes out with the fewest bruises, but I don't think any of them are going to come out as the winner."

Editor's note: This report was originally published on Jan. 9, 2019 by The Observatory, a publication of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

This report is the copyright © of its original publisher. It is reproduced with permission by WisContext, a service of PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio.