When Efforts To Halt Smallpox In Milwaukee Provoked Fear And Fury

A highly contagious disease put the population in a panic. The government's response became politicized. Less affluent neighborhoods bore the brunt of the outbreak. The best medical science of the day was doubted. An aggressive protest against public health enforcement broke out. There was even an impeachment.

It was 1894 in Milwaukee, a city divided on ethnic lines. In the north, a well-established German community. In the south, a growing settlement of Polish immigrants.

"There was the temptation always for the older groups to kind of raise their own status by looking down on those who were next to come," historian John Gurda said. "And that was certainly the case in the matter of the Poles and Germans in Milwaukee."

It did not help relations that the majority of Poles originally hailed from regions in Europe long under German control.

Drawn by job opportunities in the city's growing industrial areas, the new immigrants also eagerly bought lots to build homes.

"They had an intense desire to own land as part of the peasant's belief that land is your security. So they settled on the South Side. Just covered block after block and mile after mile with little houses," Gurda described. "The result was a house type called the Polish flat which is still a really prominent type of house on Milwaukee's South Side."

The Polish flat represented both the thrift and ambition of these immigrants. The initial small single story cottages were like starter homes. But as families saved and built income, instead of moving to a new larger house, often the flats would be jacked up, a half basement excavated and a new floor added below the original.

An isolated public health doctor

In Milwaukee's Polish flats, in 1894, a contagion was spreading. A single case of smallpox had been diagnosed in the city in January. By May there were six hospitalized as the infection spread.

Outbreaks of smallpox had remained frequent throughout the 19th century, even though a vaccine had been developed nearly a century before and the growing public health movement encouraged its use. But the treatment was met with suspicion, said by some to be a cure worse than the disease. The Milwaukee Anti-Vaccination Society launched in 1891 and had adherents among both the Polish and German communities.

The person responsible for tracking and treating an epidemic in Milwaukee at the time was the newly-appointed health commissioner Dr. Walter Kempster. The English-born physician enjoyed a national reputation for having done ground-breaking microscopic studies of the brain. Before taking the Milwaukee position, Kempster had been superintendent of the Northern Hospital for the Insane at Oshkosh, now called the Winnebago Mental Health Institute. His renown was such that he served as an expert witness in the trial of Charles Guiteau, the delusional assassin of President James Garfield.

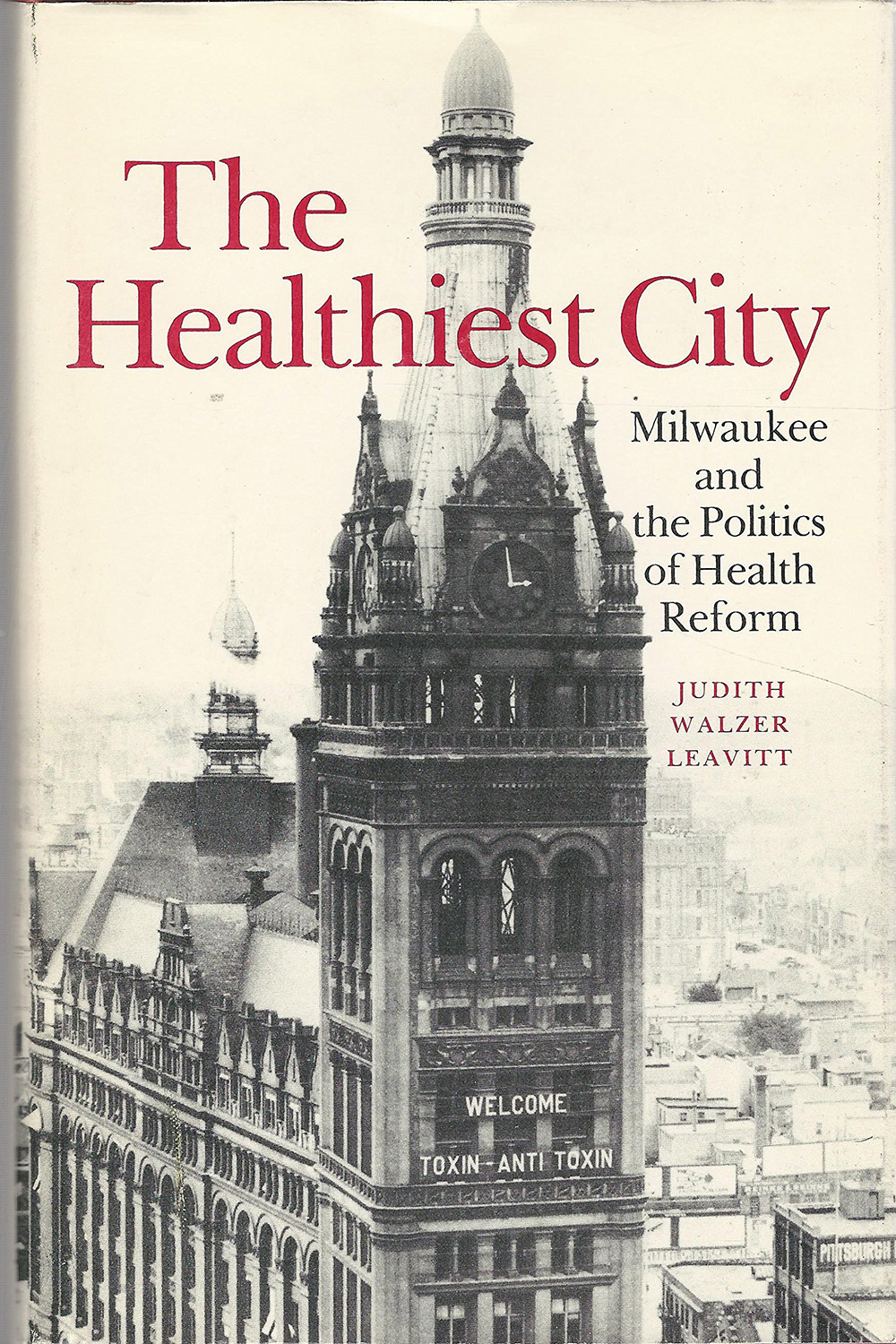

But Kempster was not a good fit for the city, as recounted by University of Wisconsin-Madison medical historian Judith Walzer Leavitt in her 1982 book, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform. His English background did not help put him in good stead with either of the city's dominant ethnic groups. Chosen for the position by a mayor seen as a reformer, Kempster still had to contend with an entrenched political establishment. The party proffered many names to add to his staff and he selected none.

The United States was still recovering from an economic depression brought on by the Panic of 1893 and political patronage jobs were plum spots for anxious jobseekers. A humorous aside from the July 2, 1894 edition of the Milwaukee Journal conveys both the vigor with which those jobs were sought and growing awareness of the smallpox problem. A story quotes the commissioner of public works who said he'd figured out how to handle "the obstreperous individuals who are looking for city jobs."

"I have been looking for a man just like you," the commissioner claimed to say to someone badgering him for a position. "We want a man to repair the floor in the Isolation Hospital." The Journal concluded, "The mention of Kempster's smallpox factory as the place of operations suddenly removes the desire for a public job."

"Kempster's smallpox factory" is a good indicator of how the Isolation Hospital, built specifically to quarantine infectious patients during epidemics, was viewed by the public. Located at 1640 S. 24th St., the hospital may have been isolated when first built, but the burgeoning South Side quickly filled in around it.

The facility's proximity was blamed by nearby residents for spreading the disease, and the prospect of being shipped to "the pesthouse" after a diagnosis terrorized many neighborhood residents. As it turned out, some would be brought there by force.

Escalating hostility

Walter Kempster began his efforts to contain the smallpox outbreak by following an established strategy of widespread vaccinations, quarantine for the sick and the hospital for the sickest. The mistrusted vaccines could not be mandated, though, and the only leverage public health officials had was barring unvaccinated children from schools. It was not an effective threat as the numbers of infected started growing as summer began and school surely felt a long way off.

Many bristled at orders to remain home and feared the Isolation Hospital, so some south siders would not report cases of smallpox to officials. With incomplete data, Kempster underestimated the threat. The press picked up on the unreported numbers and questioned Kempster leading to a hostile relationship.

"I am seriously considering the advisability of posting a notice on the door of this office to the effect that no more information regarding the smallpox will be given to the press," Kempster was quoted as saying in the Journal on July 18. "The impression has gone out from one end of the state to the other that Milwaukee is infested with smallpox."

That impression was rapidly becoming a reality as case numbers grew and grew. Kempster's tactics became more aggressive, at least in the South Side, while more affluent areas were given more leeway.

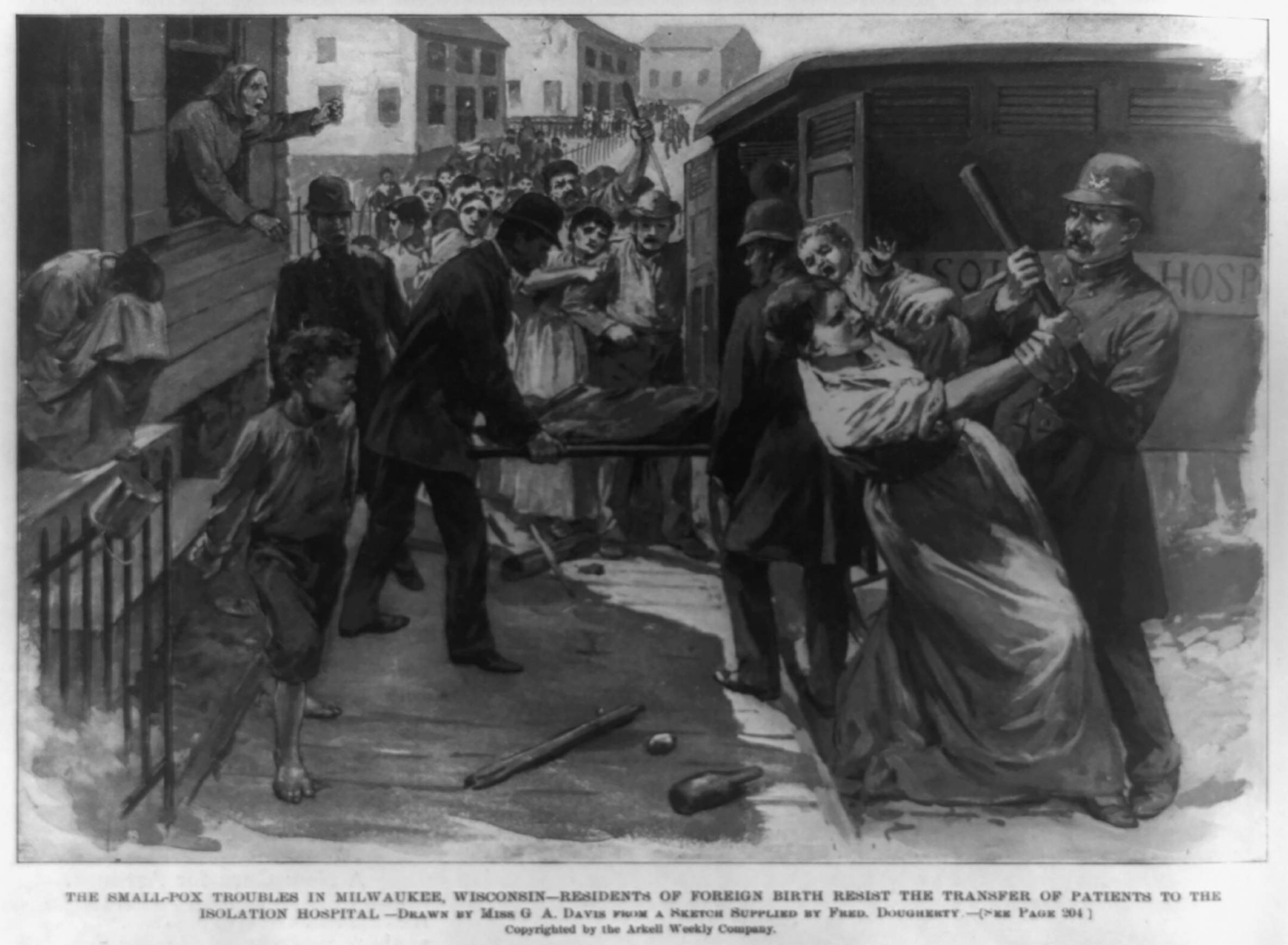

Efforts to move those infected were resisted and crowds would gather when health officials entered the neighborhood.

"The focus of the crowds' hatred was Kempster," Judith Walzer Leavitt wrote in her account. "[He] symbolized arbitrary governmental authority that subverted immigrant culture and threatened personal liberty."

The protests were far from peaceful. "Calling for his execution, the crowds demanded that 'the people's rights were paramount and should be protected.''

"Any time in America, you have someone abridging what you think of as your liberties, you're going to get pushback," historian John Gurda observed. "They were actually taking people from their own homes. Children, from their homes, and putting them in hospitals. That's on a level that if you tried that today you'd be shot."

Women played an especially significant role in what would become riots, perhaps to the delight of the Journal's headline writers: "Reckless Fury of Women."

"The men were easily subdued, but the women fought like tigers," read one breathless report. The women were described as arming themselves with potato mashers and butcher knives, even salt and pepper.

The area's alderman, saloon-keeper Robert Rudolph, was called the "moving spirit" of the demonstrations. At one, a man "shouted for the crowd to procure 'barrels of oil and burn the hospital.' About forty men started toward the hospital, but a minister, who has a great deal of influence, headed them off, and succeeded in turning them back," the Journal reported.

Rudolph took his fight from the street to the corridors of power. According to Leavitt, "he introduced resolution after resolution, ordinance after ordinance, each one concerned with limiting the power of the health department and Walter Kempster."

Ultimately, the efforts against Kempster led to his impeachment by the Milwaukee Common Council just as the epidemic was peaking in October. Physicians' disagreements over proper treatment were aired publicly during impeachment testimony, with Kempster personally cross-examining and questioning the knowledge of fellow doctors. He may have made his medical case, but it was his attitude and aggression in fighting the outbreak that doomed him.

"But, however acceptable the public found Kempster's stand theoretically, his insensitivity and inflexible behavior as revealed in the daily testimony became harder and harder to defend," Leavitt wrote. After months of the proceedings, which led the council president to question "whether we are at a circus or a session of the Common Council," Kempster was voted out of his position by a 22-14 vote.

An important public health lesson

The Milwaukee epidemic ended in 1895 after 244 deaths. Smallpox would never seriously threaten the city again.

Its legacy in the field of public health is as a cautionary tale, due in no small part to Judith Walzer Leavitt's extensive research to tell the story. The now emeritus University of Wisconsin professor of medical history compares Milwaukee's experience to a much more successful response to a smallpox outbreak in New York City in 1947.

"They just epitomize where the same policy can have very different effects depending on how it operates. In 1894, it was very discriminatory against the poorer parts of the city," Leavitt said in an interview.

New York took a more inclusive, equitable, and ultimately successful approach.

"They did it by mobilizing the community organizations around the city, PTAs, Red Cross, church groups, synagogue groups. They did it by advertising vaccination multilingually in newspapers and radio stations." Leavitt said. "And they did it in a way that was perceived as fair as opposed to Milwaukee, which was perceived as completely unfair."

Leavitt concluded, "It's a big success story and it really did teach the 20th century how to do it."

Smallpox infections were finally eradicated globally in 1980.