Elizabethkingia Is Common Bacteria, But Seldom Infects Humans

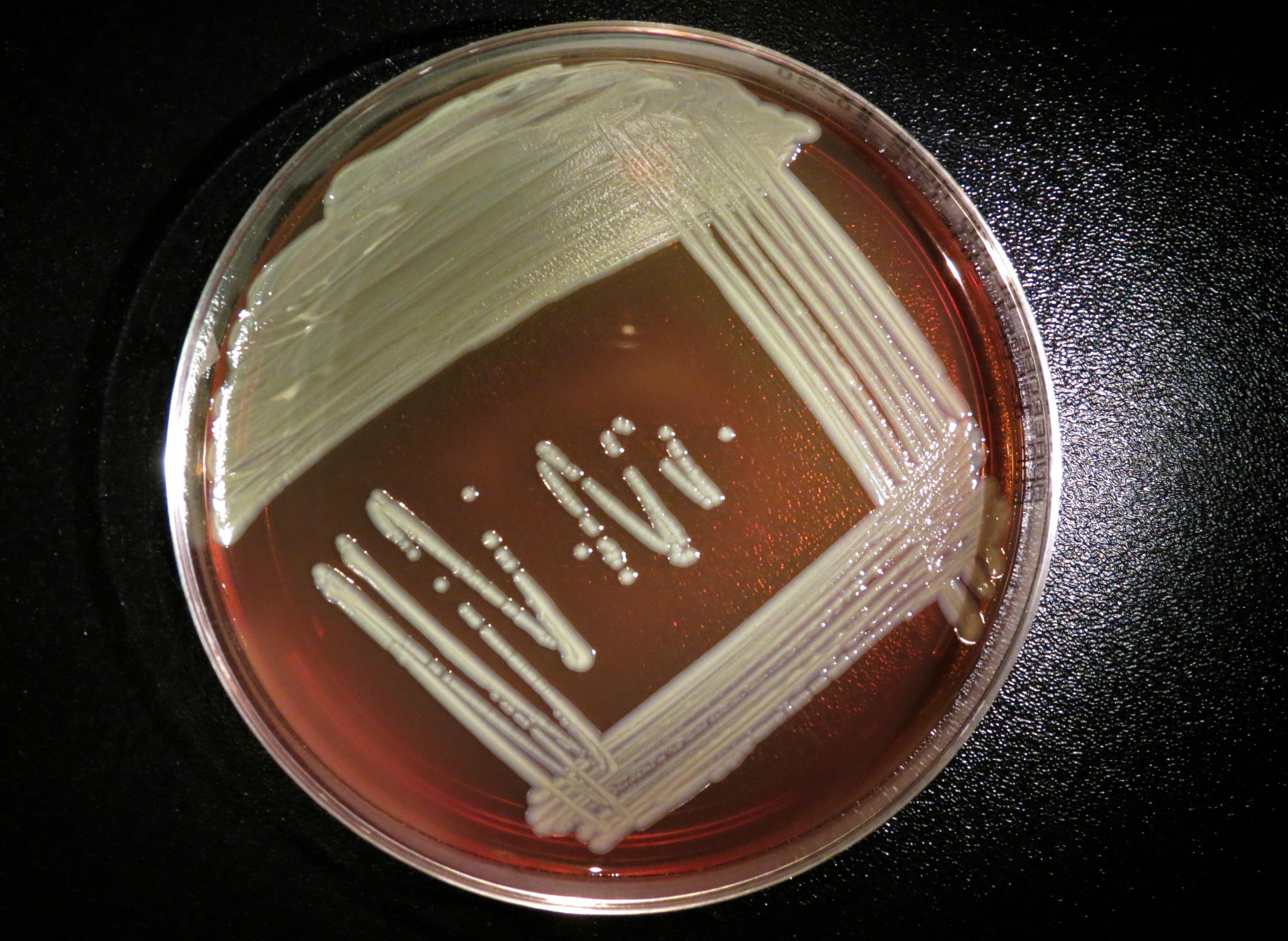

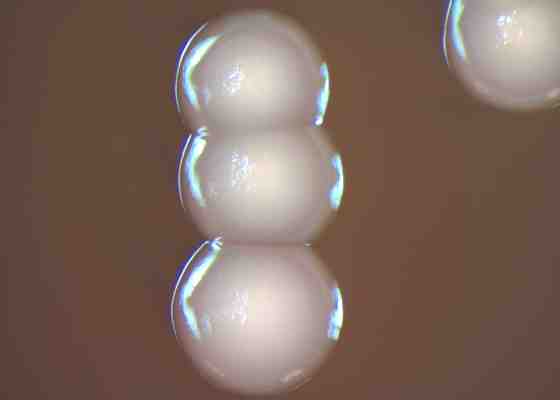

Elizabethkingia is a genus of gram-negative bacteria commonly found in soil and water. Medical and microbiological researchers have previously referred to it as Flavobacterium or Chryseobacterium. The organisms seldom cause disease in humans, but when they do, illness in adults typically manifests as a serious blood infection resistant to many antibiotics. Among infants, infection by the bacteria causes meningitis.

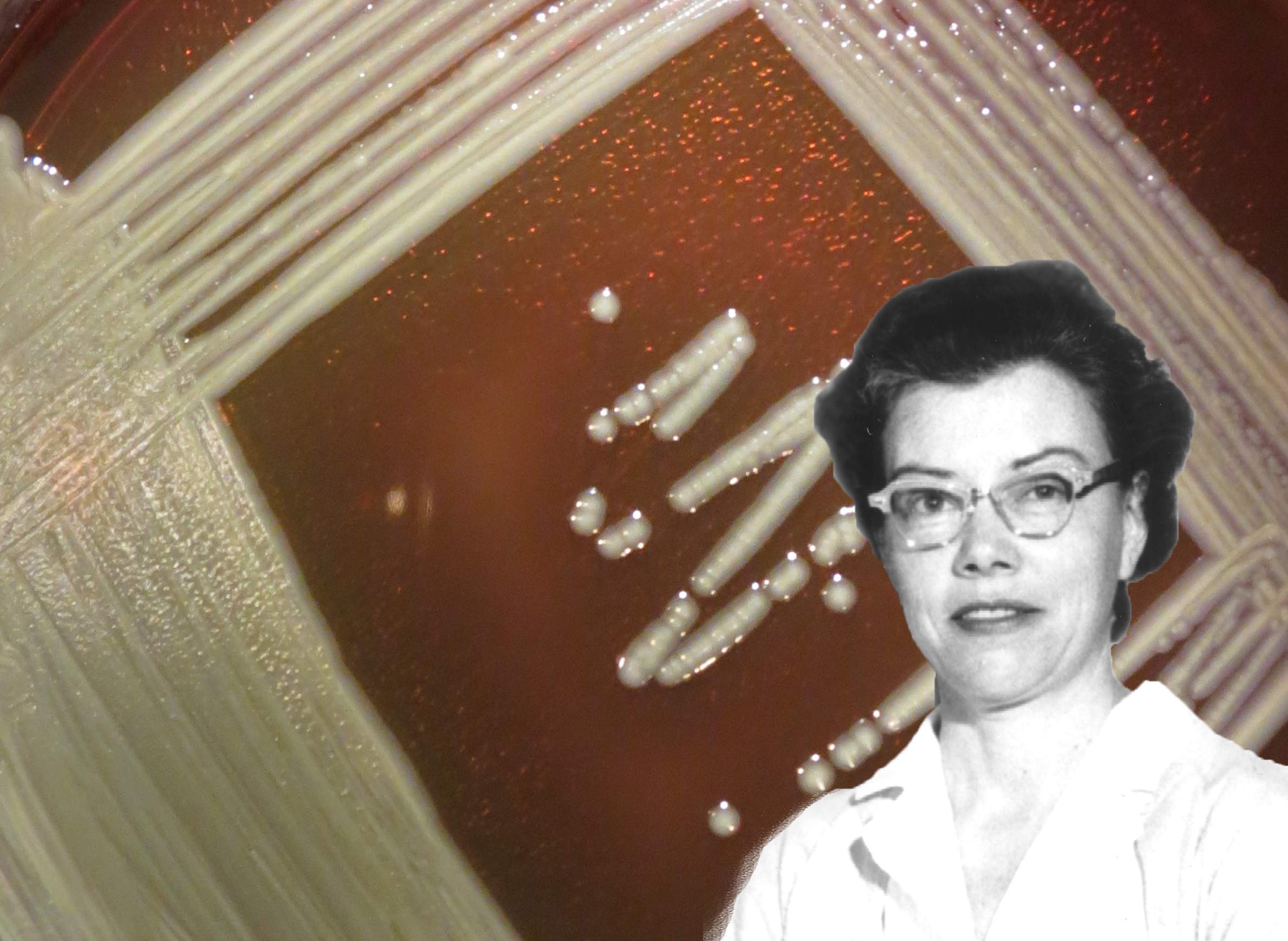

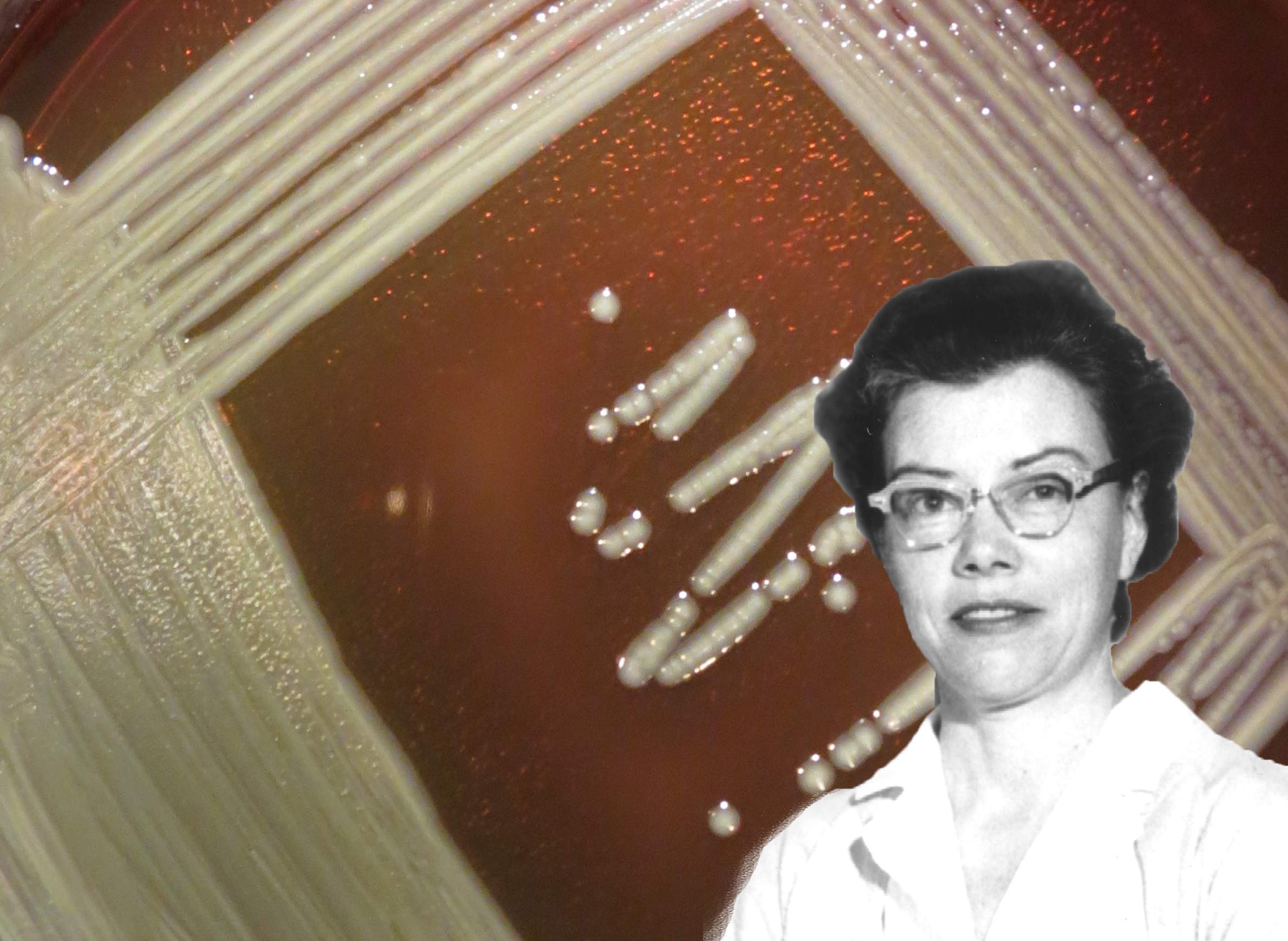

The genus bears the name of Elizabeth O. King, a microbiologist who first isolated the class in 1959. She reported the finding that year in an American Journal of Clinical Pathology paper titled "Studies on a Group of Previously Unclassified Bacteria Associated with Meningitis in Infants." Born in Atlanta in 1912, King joined the Communicable Disease Center (now the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in 1948 and worked there until her death in 1966. According to a dedication that prefaced a CDC manual, King had earned an international reputation as an expert on unusual bacteria. The Southeastern Branch of the American Society for Microbiology presents an Elizabeth O. King Award, declaring that she "took it upon herself to identify the difficult-to-identify organisms."

Researchers working in King's footsteps have refined the biological taxonomy and genetics of these bacteria. The organism King first isolated is known as Elizabethkingia meningoseptica. An addition to the genus came in 2003, after Elizabethkingia miricola was isolated in the Russian space station Mir. In 2011, Elizabethkingia anophelis was isolated from the gut of a mosquito native to west Africa. Elizabethkingia can be found in many places. "It's ubiquitous in the environment, in water and other sources that are around us," said Dr. Nasia Safdar, an infectious disease specialist at UW Hospitals and Clinics, in a March 9 interview on Wisconsin Public Radio's Central Time. "But because it's not very virulent, meaning that it doesn't attack the normal host, it only causes infections if one's immune system is unable to cope with the entry of a pathogen."

As of 2016, the genus Elizabethkingia includes the anophelis, meningoseptica and miricola species, each of which have been identified having the potential for causing infections in humans. The meningoseptica variant can infect people whose immune systems are compromised by other medical conditions, and it is reported to cause sepsis in newborns. The anophelis variant can also infect people, but these cases likely are underreported because anophelis is easily misidentified as meningoseptica.

Nationwide, 250 to 500 cases of Elizabethkingia infections are identified each year, with a few localized outbreaks in recent years, CDC spokesman Tom Skinner told the Wisconsin State Journal. Over the winter and early spring of 2015-16, and outbreak of infections stemming from anophelis was reported in Wisconsin.

Elizabethkingia-related outbreaks have often proven difficult to treat and understand. In Mauritius in 2002 and 2003, infection by the meningoseptica strain caused meningitis in eight newborns, killing two of them. The source of the outbreak could not be established conclusively. The first report of Elizabethkingia anophelis to infect a human was in the Central African Republic in 2011, when an infant girl died after getting meningitis. Her infection by proved to be resistant to many antibiotics.

A recent study on infants suffering from Elizabethkingia anophelis-caused meningitis concluded these bacteria can be transmitted from the infants’ mothers. In Hong Kong in 2012, three patients at the same hospital became ill following anophelis infections: Two newborns acquired meningitis and a mother was diagnosed with chorioamnionitis (an infection of fetal tissues). Researchers attributed both meningitis and chorioamnionitis to Elizabethkingia anophelis infections and concluded the mother transmitted the bacteria to her child.

The greater body of research on all species of Elizabethkingia, including anophelis, emphasizes their tendency to spread to vulnerable patients in hospitals. One crucial study of the first anophelis outbreak in an intensive-care unit in a Singapore hospital in 2012, suggested the bacteria spread to patients from an aerator on a handwashing faucet. Investigators found 14 strains of the bacteria in aerators in the ICU units and in a surgical ward to which patients were often transferred. Genetic sequencing determined the strains infecting patients and in the hospital environment were more closely related to the anophelis variant.

In the U.S., previous outbreaks of Elizabethkingia infections have typically occurred in hospitals, unlike Wisconsin's experience with the anophelis strain, Dr. Chris Braden of the CDC told the Wisconsin State Journal. Other studies linked hospital outbreaks of Elizabethkingia infections to the bacteria's presence in tap water or in medical devices.