How Public Health Recordkeepers Struggle With Tracking Synthetic Opioids

One of the most confounding factors of the opioid epidemic is the sheer variety of drugs involved. The wide availability of prescription painkillers and the low price of heroin certainly helped accelerate a rapid increase in opioid overdose deaths since the early 2000s. Over time, more potent drugs like fentanyl, carfentanil and illicitly manufactured fentanyl analogs filtered into the picture, not necessarily overtaking other drugs but adding to an ever-shifting mix of substances that's often unclear to the people using them.

As more people die of overdoses — sometimes after unknowingly using highly potent opioids — public health officials are also struggling for clarity. In an individual death, it's tough for standard methods of toxicology testing to reveal the presence of small amounts of chemically novel opioids, especially because many overdose deaths involve multiple drugs. That means a small amount of a rare or chemically novel opioid could be present alongside larger amounts of a more common and much better-understood drug like heroin. So death investigators may not find every drug contributing to an overdose, and may not list all of the specific contributing substances on a death certificate, coroner's report or police report.

Such omissions and blind spots become even more troublesome as health officials at state and federal level aggregate information about overdose deaths. These officials face a challenge when determining a bigger-picture perspective on the role of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids because of the long-standing conventions and systems of death reporting.

The Wisconsin Vital Records Office files and organizes locally issued death certificates and enters information about violent fatalities into the Wisconsin Violent Death Reporting System. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention then gathers such data from states and combines it in its National Violent Death Reporting System. These databases indicate the causes of and contributing factors to deaths with a widely used code called the ICD-10.

These codes are specific enough to indicate an overdose involving certain specific substances, like heroin, but lumps others into categories of drugs. In the case of fentanyl, the person filling out death records would use a category code for "synthetic opioids other than methadone," Wisconsin Department of Health Services spokesperson Jennifer Miller explained. Additionally, a given death involving opioids may fall under different sections of the ICD-10 depending on how investigators interpret the circumstances and other factors of the death. Some deaths will fall under a category within codes categorized as an "Event of undetermined intent," while others may be recorded as suicides or even homicides.

Given this system, when Wisconsin pulls together data from 72 county coroners and medical examiners, it's not going to be able to come up with a statewide number of overdose deaths specifically involving fentanyl, or furanyl fentanyl or U-47700 for that matter. Moreover, the code can't account for new fentanyl analogs that haven't been identified, and then there's the ever-present complication of overdoses involving multiple drugs. Add all this up, and it's very difficult to track trends of novel, rare or highly potent drugs' roles in overdoses.

"One challenge in monitoring fentanyl trends is lack of specificity in cause of death codes on the death certificate," Miller said. "We are unable to identify deaths attributed specifically to fentanyl because we do not have a code with that level of specificity. We are able to report synthetic opioid-related deaths, which do include fentanyl but also other synthetic opioids such as meperidine."

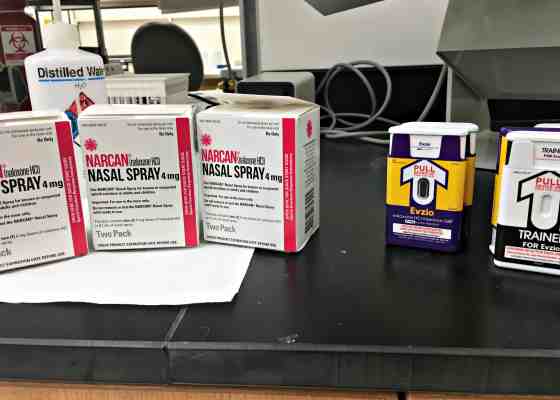

With help from a CDC grant, the Wisconsin DHS recently began a project that will help it create more detailed records of the drugs and other factors that contributed to overdoses, both fatal and non-fatal. This effort will begin with information on deaths during the second half of 2016, said Brittany Grogan, coordinator for the Wisconsin Violent Death Reporting System. The information entered in this database will include every substance an overdose victim tested positive for, toxicology reports and more information about the context of the overdose, such as whether the victim had a history of substance use or had an opioid prescription.

"The goal of the data being put into the NVDRS is to really understand context and risk factors that you might not get through a death certificate," Grogan said.

In the long run, this information could help officials and the medical community craft better approaches to treating and preventing substance use.

Coding deaths at the local level

The new project by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services depends to some extent on the cooperation of medical examiners and coroners across Wisconsin's 72 counties.

Only a handful of Wisconsin counties have medical examiners offices with actual medical doctors in charge and the capacity to perform autopsies or carry out toxicology testing in-house. Most have either an elected coroner or a lay medical examiner who is not necessarily a physician. The state doesn't regulate coroners or medical examiners, so the way these officials fill out death certificates and other reports isn't necessarily standardized.

"There's a lot of different phrases that might be used by different offices," said Dr. Doug Kelley, chief medical examiner for Fond du Lac County and a physician. "It kind of depends on the circumstances of the case and the philosophy of whoever's signing the death certificate, to be honest."

One silver lining to this practice, though, is that many smaller counties rely on bigger and more-equipped counterparts to perform autopsies and fill out death certificates. This may help to enforce a measure of standardization.

Kelley's office, for instance, handles autopsies for 13 other counties, though they could conceivably contract out some autopsies elsewhere if needed, he said.

"There isn't a standard of operation for a coroner or medical examiner's office in Wisconsin, but for the most part investigating deaths is a team effort and law enforcement is always involved," he said. "Occasionally you might have other agencies involved….[which] usually means that they're not going to slip through the cracks."

Analysts at the DHS may not have any regulatory power over county coroners and medical examiners, but communicate with these officials about the importance of detailed reporting and testing in drug-involved deaths, said Michelle Smith, a supervisor in the DHS Vital Records Office. DHS record keepers also follow up with county officials for more details about overdose deaths when necessary. "For the most part they are being cooperative," she said.

Smith has found that medical examiners have various reasons for using the discretion they have in Wisconsin. Often that takes the form of not wanting to list specific drugs on a death certificate or report.

"Some of their hesitations are, one, they don't want to be held to it if it goes to court listing specific drugs...I think getting toxicology is another," Smith said. "[In] our 72 counties, some budgets are very large and some budgets are very small, so they have to be really choosy about toxicology and that kind of thing."

"I think there's also a sensitivity to the families," she added, noting stigma surrounding substance use and overdoses.

The DHS and CDC are hoping to gather more detail in part because it's not really possible to add novel drugs to the ICD-10 codes as they emerge.

"That has been a challenge in monitoring something like fentanyl," DHS epidemiologist Crystal Gibson said. "We have to report synthetic opioids as a proxy measure for fentanyl, but the ICD-10 coding scheme is not this rapidly changing system that can incorporate these new substances."

With the more detailed information they are beginning to gather about overdoses, DHS staff hope to be able to provide more detailed analyses of how opioids affect different groups of people around the state — exactly the kind of analysis that's been lacking in Wisconsin.

Grogan thinks the DHS project could also provide more insight into the mental-health issues with which substance use is so profoundly connected.

"There's a lot of gray area between overdoses and suicides and we don't necessarily know how that will be improved, but figuring out intentionality around some of these deaths is something that we would hope would happen," she said.