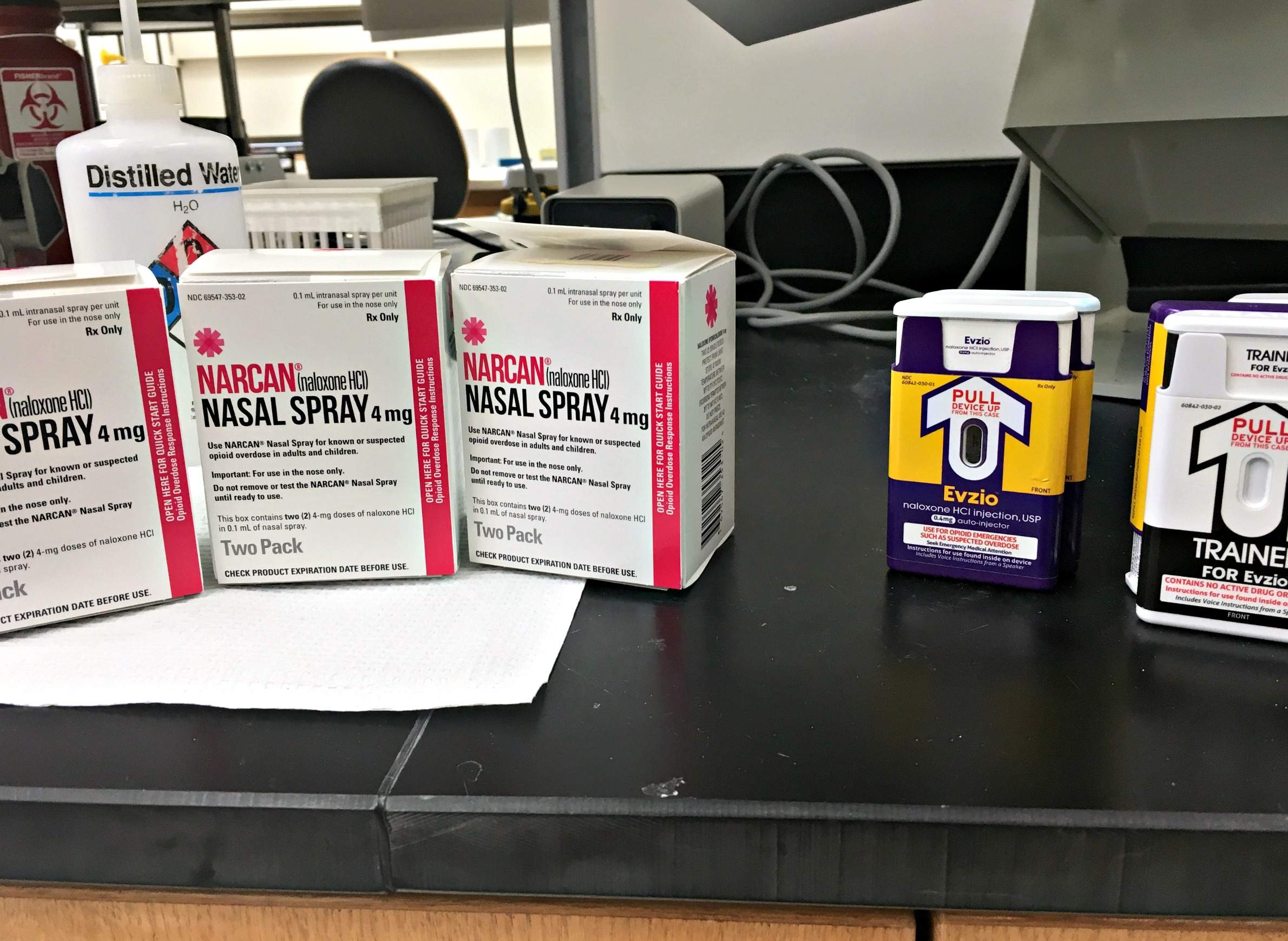

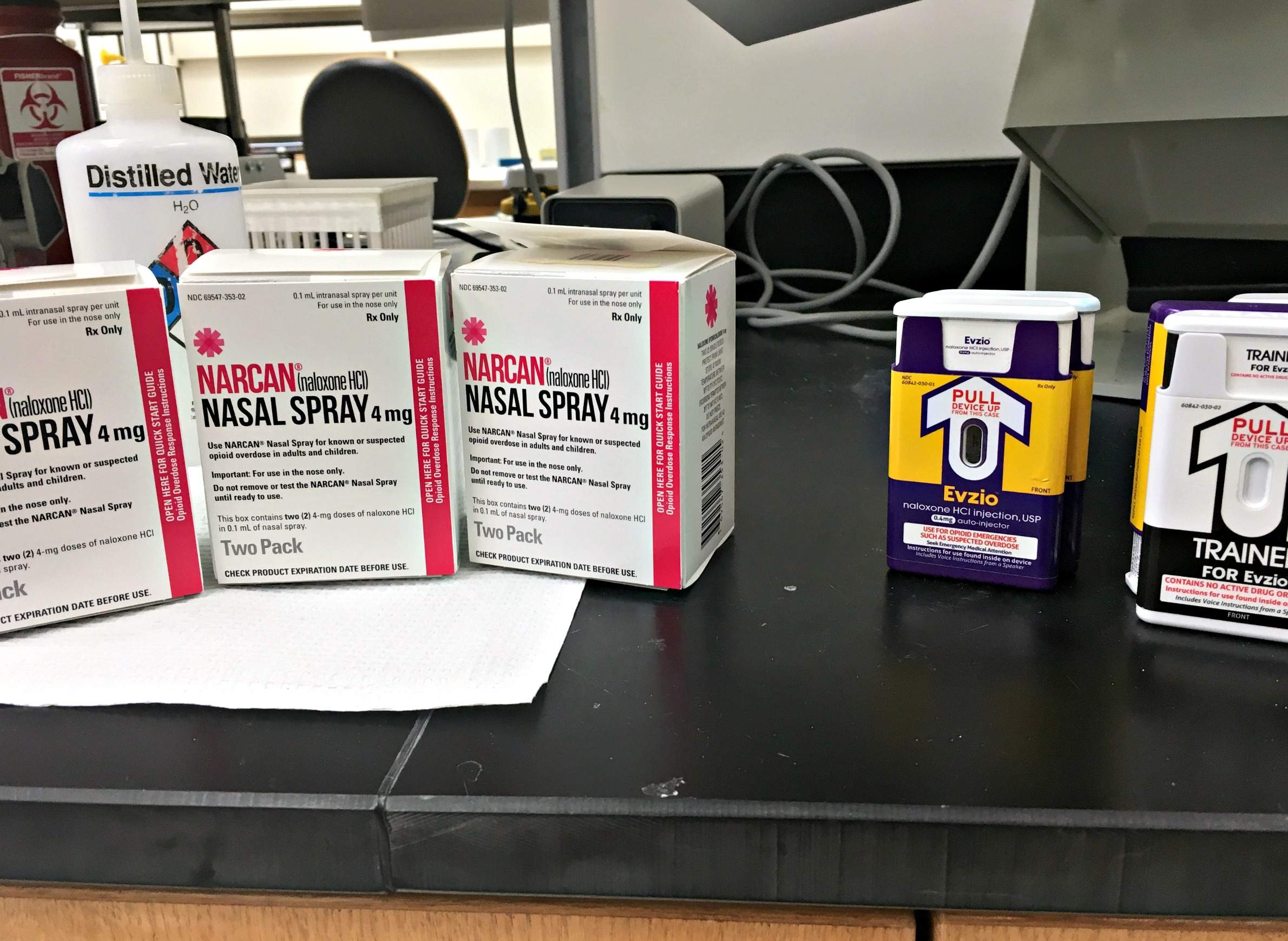

Law enforcement, first responders and toxicology labs keep drug overdose treatments like Narcan and Evzio on hand in case of occupational exposure to opioids.

Law enforcement, first responders and toxicology labs keep drug overdose treatments like Narcan and Evzio on hand in case of occupational exposure to opioids.

As powerful drugs like fentanyl, carfentanil and unfamiliar but chemically similar variations creep into Wisconsin's illicit opioid supply, they endanger users who may not realize how potent these substances are or even that they are present. But these novel opioids also pose dangers to the first responders and lab technicians who deal with the aftermath of overdose deaths and drug-related arrests.

When ambulance crews and law enforcement officers show up at the scene of an overdose, they don't necessarily know which specific drugs to expect at the scene. The user might not have known either, as substances like fentanyl and carfentanil are often cut into heroin or otherwise sold as something they're not. Fentanyl and its analogs are far more potent than heroin and can be absorbed through the skin — in legal medical settings, fentanyl patches are used to treat pain. If a first responder handling an overdose scene touches or perhaps inhales a small amount, he or she could also be at risk.

So far, state and federal authorities have not documented any incidents in which a first responder died after being exposed to synthetic opioids on the job. But exposures have happened. One widely circulated anecdote tells of two New Jersey police detectives who accidentally inhaled a small amount of fentanyl (mixed with both cocaine and heroin) while responding to a crime scene. Both officers reported trouble breathing, elevated heart rates and nausea, and were taken to a hospital to recover.

It's becoming increasingly common amid the opioid epidemic for police and EMS workers to carry the emergency overdose remedy naloxone — sold commercially as Narcan — and they're increasingly aware now that they might have to use it on themselves or each other.

Law enforcement and medical professionals who deal with illicit or dangerous drugs have known of these risks long before the current opioid crisis, and are trained to use protective gear (including gloves and masks) and handle emergencies on the job. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers resources and information on the occupational risks fentanyl creates. While government agencies have long had established safety protocols for how narcotics and other chemicals are to be handled during investigations, what heightens this issue is the growing prominence and potency of synthetic opioids.

With fentanyl and carfentanil playing a role in more overdose deaths in Wisconsin, emergency officials and drug investigators in the state are thinking a lot more about the dangers they face. And as illicit drug manufacturers pump out novel chemical variations of fentanyl that haven't been studied in a legitimate medical context, emergency responders go into situations not knowing what the drugs are, how they effect a user, or whether or not they can be absorbed through the skin.

"There's really no way of determining, pre-hospitalization,what that medication is or how much that individual has consumed," said Fred Hornby, conference and sales director for the Wisconsin EMS Association and a longtime emergency medical technician in Milwaukee. He worries about whether EMS agencies around the state will be able to afford the naloxone they need.

"The prices of naloxone are going way way up, sky-high, as more and more people are becoming addicted and more and more people are able to give it," Hornby said. "In Wisconsin, about 80 percent of our services are volunteer in nature, which means they don't get paid for what they do and the reimbursement issue is of a large concern."

Emergency responders who've learned to use naloxone also have to adjust as novel and more powerful opioids come into the picture. If someone has overdosed on carfentanil, they may need multiple doses of naloxone, whereas someone overdosing on heroin or oxycodone may only need one. If a person overdoses on a novel opioid that hasn't been studied very much or tested on humans, that calculation becomes even harder for a first responder under pressure.

"It's the ones we don't know about — what are they mixing today?" Hornby said.

Naloxone is also making its way into the lab. Technicians at the Wisconsin State Crime Lab facility in Milwaukee and the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene in Madison have recently been trained to use naloxone, and both labs have multiple kits on hand in case of an exposure. Some technicians might only actually test for opioids present in blood, urine or vitreous fluid samples, and are therefore less likely to be exposed to the drug itself.

Labs do keep reference samples of drugs to have a baseline of comparison for the chemical makeup and concentrations of test results. Sometimes these samples are in powder form, but lately it's become more common for them to be dissolved in liquid, said Amy Miles, forensic toxicology director at the state hygiene lab. However, such reference samples won't exist for a novel opioid that's been illicitly manufactured and has never been formulated or tested in a legitimate medical context.

"Since there isn't a lot of concrete data out there that it's not transdermally absorbed, coupled with the potential for some of the analogues to be aerosolized, we wanted to take every precaution necessary," Miles noted in an email [emphasis in original].

Both Miles and Leah Macans, head of safety for the Milwaukee state crime lab facility, said they began hearing about labs acquiring naloxone only over the past couple of years while attending professional conferences. But this medication's presence is not necessarily a disturbing presence in a laboratory setting, where workers have already been trained to take safety precautions and use safety equipment ranging from gloves and masks to fire blankets and eyewash stations. And even in public places, people are increasingly accustomed to seeing first aid kits and automated external defibrillators (also called an AED).

"Narcan in the lab is, I think, just more about people feeling that we're taking the steps as a lab to make sure that everyone is safe," Macans said. "I think it's unsettling that there's potential for that exposure, but we never know what we're going to get here for cases."

At the state crime lab's Milwaukee location, which gets a positive test result for fentanyl just about every day, the naloxone kits are distributed strategically, Macans said. A few are kept in the controlled substances lab, a few are placed in the evidence intake area where staff handle drug-related evidence before testing, and another is located next to an AED unit.

Robert Bell, who leads the federal Drug Enforcement Administration's Milwaukee office, said that some DEA agents are trained in the use of naloxone and some are not. He said the agency tells its personnel to keep potential opioids sealed up as much as possible before they can be tested in a controlled laboratory setting.

While saying that he didn't want to "bellyache" on behalf of law enforcement given all the harm opioids have done to families across the country, Bell acknowledged that officials have a heightened concern these days about exposure.

"We've very concerned about our investigators and agents," he said.