Illicitly manufactured analogs of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, have overdose death investigators playing catch-up.

Illicitly manufactured analogs of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, have overdose death investigators playing catch-up.

Over the course of 2016, Richland County in southwestern Wisconsin had five drug overdose deaths, one of which involved a synthetic opioid. This latter case startled the county coroner's office. It likewise surprised the Dane County Medical Examiner's office, which handles autopsies and toxicology testing for Richland and several other counties in the region. The coroner found that the combined effects of multiple drugs, including a relatively rare synthetic opioid, contributed to the death.

"One of them was something that the ME in Madison hadn't even seen," said Kathy Rossing, Richland County's deputy coroner. This drug turned out to be U-47700, an opioid patented in 1976 but never put into medical use for humans. This substance has been connected to overdose deaths in multiple states, including Kansas and Ohio. In November 2016, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration placed U-47700 on its Schedule I list of controlled substances, and several states have scheduled it as well, including Wisconsin.

Many opioids have a history of legal and regulated medical use. That means a pathologist testing blood, urine or vitreous fluid for such drugs has a couple of important reference points: The known chemical structure of a given substance, and what amount of each are appropriate in a person's system, that is the therapeutic level. In the case of U-47700, the latter baseline does not exist.

"[The Dane County Medical Examiner's office] had to try to find a lab that actually would test for this, and then of course there's no therapeutic levels because it's not a prescribed drug," Rossing said.

Increasing overdoses, finite resources

Synthetic opioids are a type of drug similar in chemical properties to opiates like morphine and codeine. They're designed and manufactured in laboratories, and marketed and prescribed as painkillers, a type of drug known as an analgesic. Examples of synthetic opioids include pharmaceuticals like oxycodone, hydrocodone and fentanyl, as well as addiction treatment drugs like methadone and buprenorphine.

These drugs are a growing culprit in Wisconsin's overdose deaths, especially since 2012, as tracked by the state Department of Health Services. This data is not tabulated by specific drugs. Moreover, many overdose deaths involve more than one substance. The 2016 Wisconsin Epidemiological Profile on Alcohol and Other Drug Use — one of the state's major public health reports, published every other year — makes no specific mention of fentanyl, and offers no breakdown of the effects of specific opioids except for heroin and methadone.

The decade-long rise in overdose deaths puts growing demands upon Wisconsin's coroners and medical examiners. Of Wisconsin's 72 counties, about 40 have a coroner who is elected and not necessarily a health professional. In some counties, including Richland, the coroner is a part-time job. Still other counties have an appointed medical examiner who is a layperson and not a doctor.

Only a handful of Wisconsin counties have a medical examiner's office with an actual medical doctor at the helm. This system means most county coroners and medical examiners depend on better-equipped counties, state labs, private labs and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine's Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine for assistance with tests and autopsies.

Agnieszka Rogalska, who serves as deputy medical examiner for Dane and Rock counties and is a licensed physician, said there are only 10 forensic pathologists in Wisconsin, doctors who specialize in analyzing the remains of people who die sudden or violent deaths.

In Richland County, investigating even a handful of overdose deaths per year has has its part-time, on-call coroners feeling stretched thin, said Rossing.

"Every suspected drug overdose is supposed to be autopsied because there are findings during autopsy that can confirm or negate that it is an overdose, so that's a big expense, around $1,450 every time," she said. "A little county like ours...that's a lot of money out of our budget."

Rossing stresses that she's happy with the service Richland County gets from the Dane County Medical Examiner’s Office, but worries about straining resources if overdose deaths continue to increase.

"There's no way to cut the budget when somebody overdoses and has to be autopsied," she said.

A game of chemical catch-up

The threat of a synthetic opioid called carfentanil hit home in Wisconsin in April 2017, as the Milwaukee County Medical Examiner linked the substance to several overdose deaths. Only days later, authorities in Dane County identified the drug as likely being responsible for an overdose in the Madison suburb of Middleton.

The medical community says carfentanil is 100 times as potent as fentanyl, another synthetic opioid responsible for a growing number of overdose deaths in 2016. Both drugs are in turn far more potent than heroin or morphine, and often end up killing people who've unwittingly bought them, typically mixed into heroin or sold under the guise of heroin or prescription pills.

No one drug has ever been the sole culprit in the opioid crisis, so it would be hyperbole to say that fentanyl or carfentanil have replaced heroin or prescription painkillers. Due to the erratic, impure nature of the illegal drug supply and the habits of individual users, opioid overdose deaths frequently involve multiple substances, including different forms of opioids, benzodiazepines and alcohol. Sometimes the combinations are deliberate, and sometimes users simply don't know what they're taking.

Fentanyl has taken a bigger toll in Wisconsin over the past few years, to judge by testing in overdose death cases and operating while intoxicated investigations.

"Since 2015, our fentanyl cases have increased. In 2015 it wasn't in our top 20 drugs we detected in drivers, however, in April 2016 it was our 18th most common drug," said Amy Miles, director of forensic toxicology at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene in Madison. "By September 2016 it moved up to the 15th most common drug detected in drivers. In our death investigation cases, in 2013, fentanyl was our 11th most common drug detected and as of April 2016 it was number 8."

In Dane County, deputy medical examiner Agnieszka Rogalska said her office sees overdose cases where people combine heroin and fentanyl.

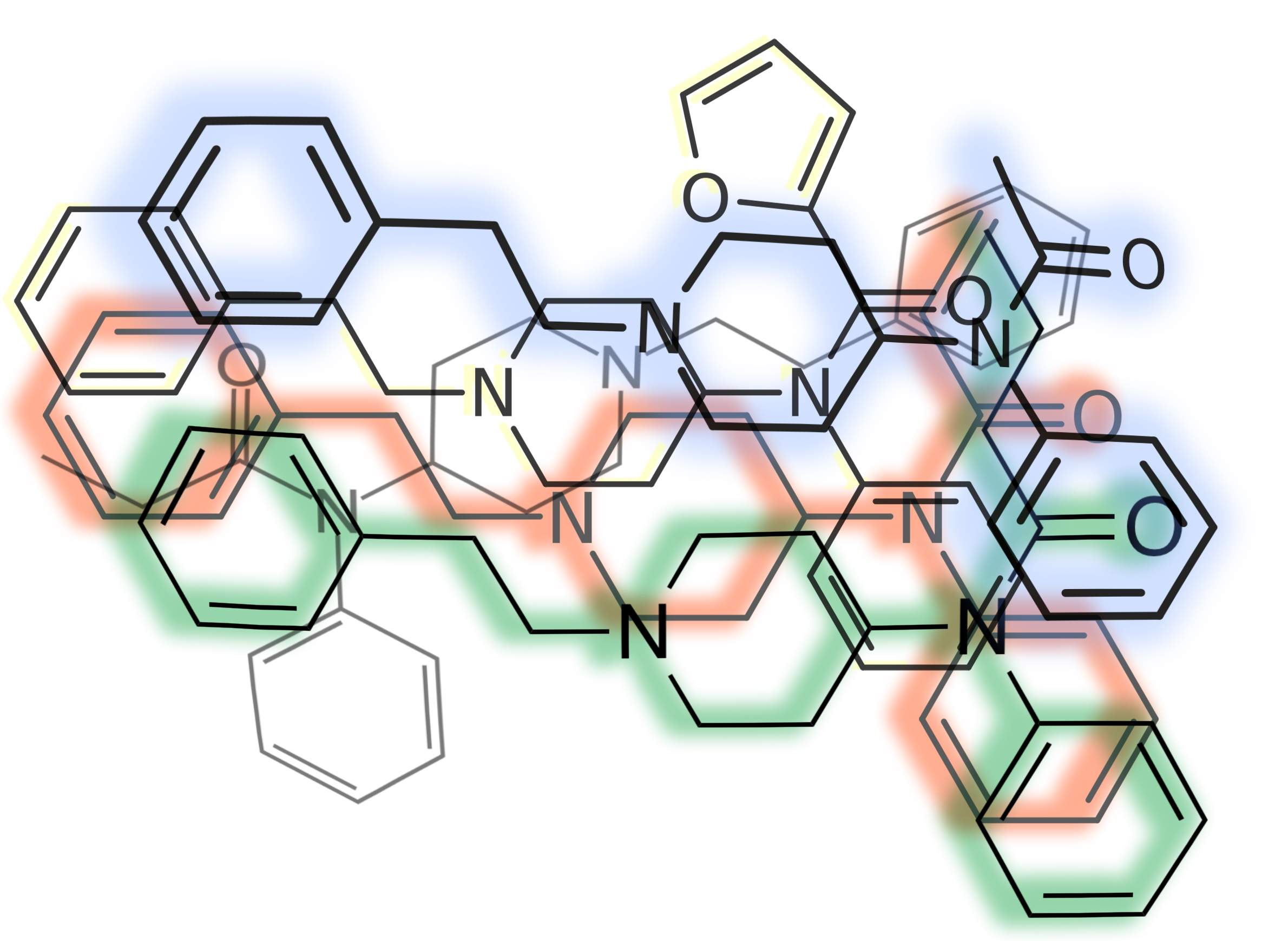

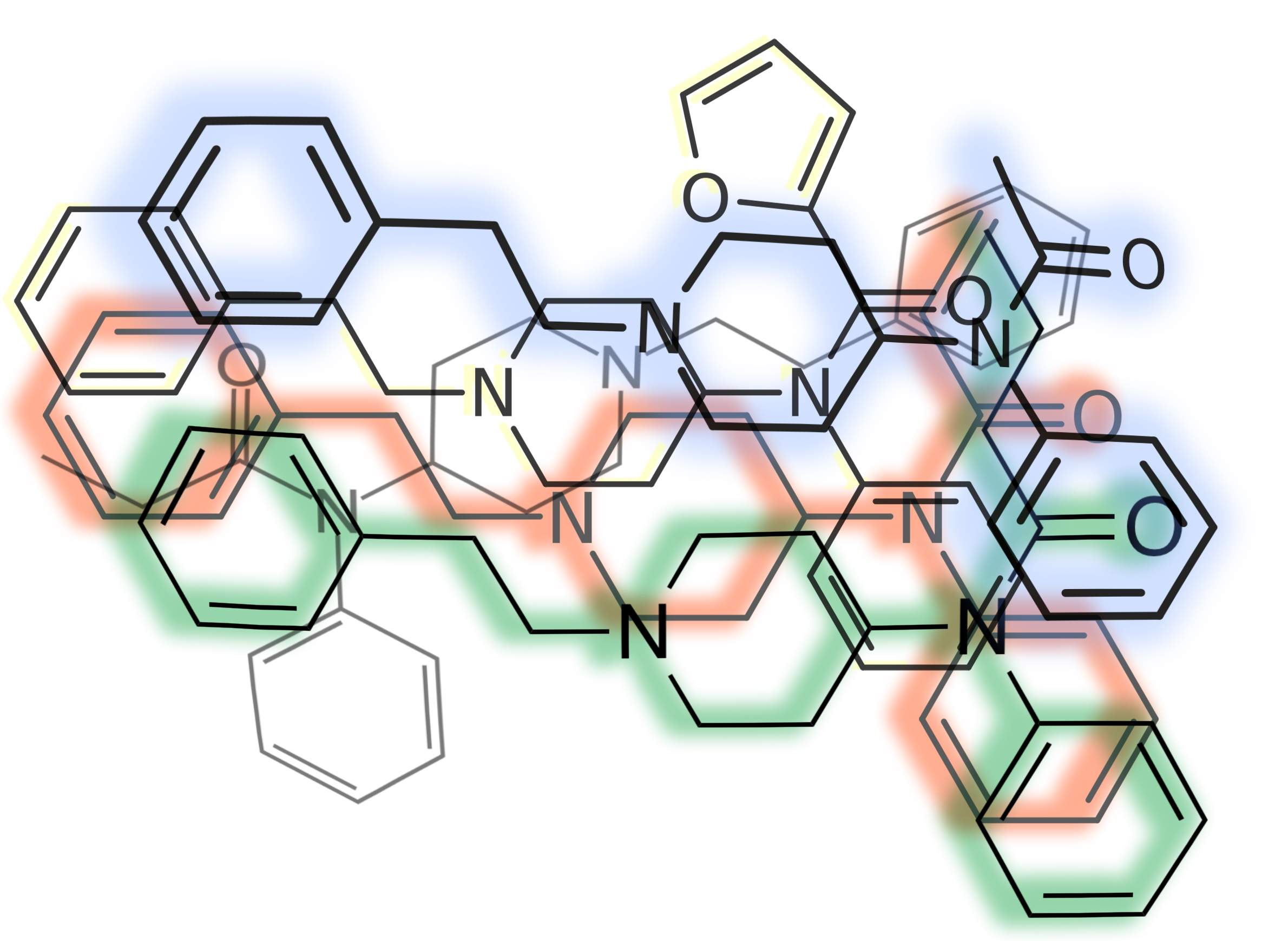

The science of synthesizing opioids is not slowing down, and the regular creation of new drugs is making it harder for health officials to understand and keep up with the epidemic. Chemists working with the precursor chemicals for fentanyl and other opioids are manufacturing powerful new drugs. Some of these opioids have a similar chemical structure to fentanyl. And some of these chemicals are truly novel, with no pre-existing counterparts in the medical world. Because health officials and law enforcement don't already know what they are, they won't always be detected in toxicology tests of overdose victims.

The people illicitly creating fentanyl analogs are likely very good chemists, Miles said. They have the capacity to create hundreds of new formulations, leaving toxicologists constantly scrambling to catch up. These novel opioids are often manufactured overseas — the U.S. has accused China of being a major source — and sold on the internet. They're often unregulated, as the government can't ban a drug it can't identify, even though many precursor chemicals are regulated.

"We have to be able to prove that the standard we're judging everything against is a certified reliable standard, so for me to go to the Silk Road [a defunct online black market] or some of these under-the-cover internet sites, I can't use that kind of stuff," Miles said. "It's coming out of Joe's garage and you don't know what Joe's making."

Novel synthetic opioids, some with a "fentanyl backbone" but an otherwise distinct chemical makeup, have never been tested. Therefore medical professionals do not have agreed-upon therapeutic or even safe levels to refer to in testing, Miles said. The state hygiene lab, like Dane County, provides testing services to counties that don't have their own laboratories and pathologists, which in Wisconsin is the vast majority of counties.

In toxicology testing, a pathologist generally has to go in knowing what he or she is looking for. For instance, if the circumstances of a death point to a heroin overdose, the state hygiene lab will use immunoassay methods to test for morphine and for the chemical created when the body metabolizes heroin. If that test comes up positive, the lab knows the person likely used opiate drugs. Technicians then conduct more tests to narrow down the specific substance or substances involved.

Confronting uncertainty

Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene forensic toxicology director Amy Miles is confident that her operation does a good job of identifying common and better-known opioids. The state lab has helped to shed light on emerging synthetic opioids like U-47700 and furanyl fentanyl, which has contributed to overdose deaths in Milwaukee.

Miles said that if toxicologists, state and local health officials, and law enforcement all communicate with each other about what they're encountering, it can help labs keep up with new or modified drugs not usually targeted in their testing. But to track down unknown and novel opioids more thoroughly, the lab would need additional equipment.

"These modifications can be just enough that if you're not using the right instrumentation, we're not going to see it," Miles said.

Miles is not convinced that novel synthetic opioids are playing a huge role in overdoses around Wisconsin, but said it's frustrating to not have a more complete picture.

"You hear a lot of reports from Ohio and Miami [Florida] where they have huge onslaughts of several people overdosing" due to novel synthetics, she said. 'We haven't had, that we know of, this massive influx...but at the same time we're not testing for everything."

Agnieszka Rogalska of the Dane and Rock County Medical Examiner's offices concurred that, so far, novel synthetic opioids appear to be less of an issue in Wisconsin than in some other states, but noted the need for vigilance.

"We're seeing this in Wisconsin, but we just don't have a way of knowing what the distribution is," she said.

Rogalska likewise stressed the importance of local coroners and medical examiners getting educated about emerging opioids.

"Your worst enemy is thinking that something is normal or that you can identify it," she said.