Discovery Of CWD Prions In Soil Adds Piece To Deer Disease Puzzle

After years of Wisconsin testing fewer deer for chronic wasting disease but finding more cases of infections, a new study offered some additional clues about how CWD might spread through the environment.

Malformed proteins called prions cause CWD, a neurodegenerative condition that always kills its victims and so far has only been found in deer and closely related animals like moose and elk. Prions are the culprit in several human and animal neurodegenerative diseases, including the vicious Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans and bovine spongiform encephalopathy ;(or mad cow disease) in cattle.

Researchers know that prions can jump from animals to humans, but have not yet established whether the prions that cause CWD can infect humans. Scientists who study CWD try to strike a balance, saying they're not ready to sound the alarm about humans contracting the disease from venison or other pathways, but admitting that the consequences would be dire if that happened.

Meanwhile, researchers are still trying to better understand how CWD spreads among deer, and new findings offer another piece to the puzzle. How the disease is transmitted is a compelling unknown, given that Wisconsin wildlife officials first discovered CWD in the state around the turn of the century, and have since found it in deer across more than two-thirds of its 72 counties.

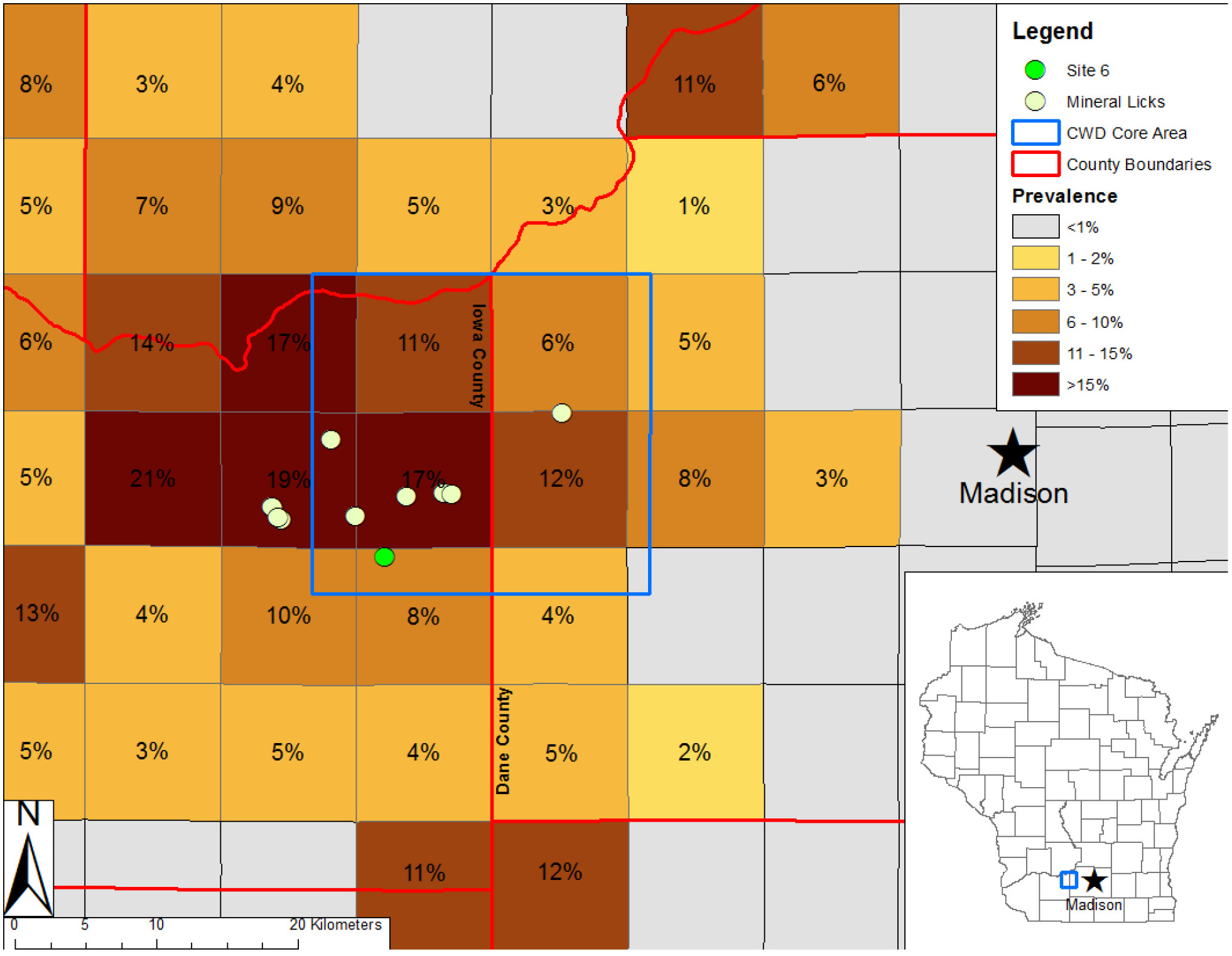

In a paper published in the journal PLOS One, University of Wisconsin-Madison soil sciences professor Joel Pedersen and collaborators determined that soil and water can serve as reservoirs for the deadly prions. CWD researchers have long suspected that the prions make their way into the plants deer eat, by taking up tainted soil or by being exposed to urine, feces or bodily tissue of infected animals. Pedersen specifically looked at the soil around mineral lick sites in Iowa and Dane counties in southwestern Wisconsin, located dead-center of where the disease started and is most serious in the state.

Mineral licks are spots where deer and other wildlife gather to literally lick up essential nutrients like sodium and magnesium. Humans create artificial mineral licks to attract wildlife —10 out of the 11 sites examined in the UW study were artificial.

Pedersen detailed his findings in a May 18, 2018 interview with Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now.

"It's the first time that prions have been discovered in naturally contaminated soils," Pedersen said. "We found them at sites where deer congregate. Whether they are at sufficiently high concentrations to cause transmissions and contribute to epidemics is not clear at this time."

Pedersen said it's not clear how long prions can actually linger in soil before disintegrating, but they are notoriously hardy. They are so heat-resistant that the only way to make meat from an infected deer prion-free is probably to incinerate it — sorry, concerned venison lovers.

A literature review Pedersen co-authored in 2011 suggests that the chemicals and microorganisms in soil aren't particularly effective at breaking down prions, though he has also discovered at least one notable exception.

"Several reports have shown that prions can persist in soil for several years," the literature review noted. In any case, if prions are present in soil, that means places where deer congregate could be hotspots for CWD. As Pedersen told Here & Now, "These are locations where deer actually consume soil."

Limitations on luring deer with artificial bait could help to address such concerns.

Conservationists and scientists have complained for years that Wisconsin officials are doing too little to track and limit the spread of CWD. Gov. Scott Walker proposed new regulations that would require deer farms to beef up their security fences and prohibit hunters from moving deer carcasses outside of known CWD-infected areas. Deer farmers and hunting ranchers, who've often argued that they're unfairly scapegoated in the CWD conversation, oppose Walker's proposal, while Wisconsin's Native American nations, long a voice on CWD and other conservation issues, are asking for "a seat at the table" in discussions over the new rules.

Meanwhile, the broader implications of Pedersen's research remain unclear. Materials that make their way into the soil can also leach into groundwater or get washed into lakes and streams, but Pedersen said he does not yet see a threat of CWD prions ending up in these places. In the interview, he reiterated that there's currently no evidence of CWD making the jump to human beings, but that still leaves a lot for scientists to figure out how is spreads among deer.

"We and others have for many years have hypothesized that environmental routes of transmission, such as via soil and water, may contribute to CWD epidemics," Pedersen said. "The relative importance of environmental routes versus contact between an infected animal and an uninfected animal is not clear."