The Bygone Era Of Marshfield's Rural Taverns

Situated not too far from the geographic center of Wisconsin, Marshfield is a small city perhaps best known for the medical clinic bearing its name. Its population of almost 20,000 has remained fairly stable over the past 40 years, yet, like many communities around the upper Midwest, Marshfield has seen dramatic changes in its rural surroundings.

Marshfield's growth owes quite a bit to its central location. Along with lumber, Marshfield's early economy was defined by agriculture. Settlers took advantage of the region's rather flat landscape to farm, particularly grain and dairy. Since the community was on a main rail line, nearby farmers had direct access to markets. Marshfield's surrounding agricultural landscape would become dotted with farms, grain mills and cheese factories.

Mills emerged as important social hubs where farmers would deliver their products and speak with neighbors while enjoying a beer. Like much of Wisconsin, Marshfield was settled heavily by German immigrants, and even by the 2010s, the proportion of its residents claiming this ancestry was 44%. As time passed, both changes to technology and transportation increased efficiencies, and fewer grains mills dotted the rural landscape. However, a desire for socialization — and beer — remained.

Tied to their German heritage, many Wisconsin communities would support at least one brewery. In Marshfield, at least one brewery was in operation for nearly a century: M. Bourgeois Brewery from 1878 to 1882, Emil P. Scheibe & Albert Schneider Brewery from 1890 to 1893, Marshfield Brewing Co. from 1893-1920 and again from 1933-1966 (the gap being Prohibition) and J. Figi Brewing Co. from 1966 to 1967. Over the same time, taverns took root in surrounding rural areas to serve the breweries' products and as gathering places for the local agricultural workforce.

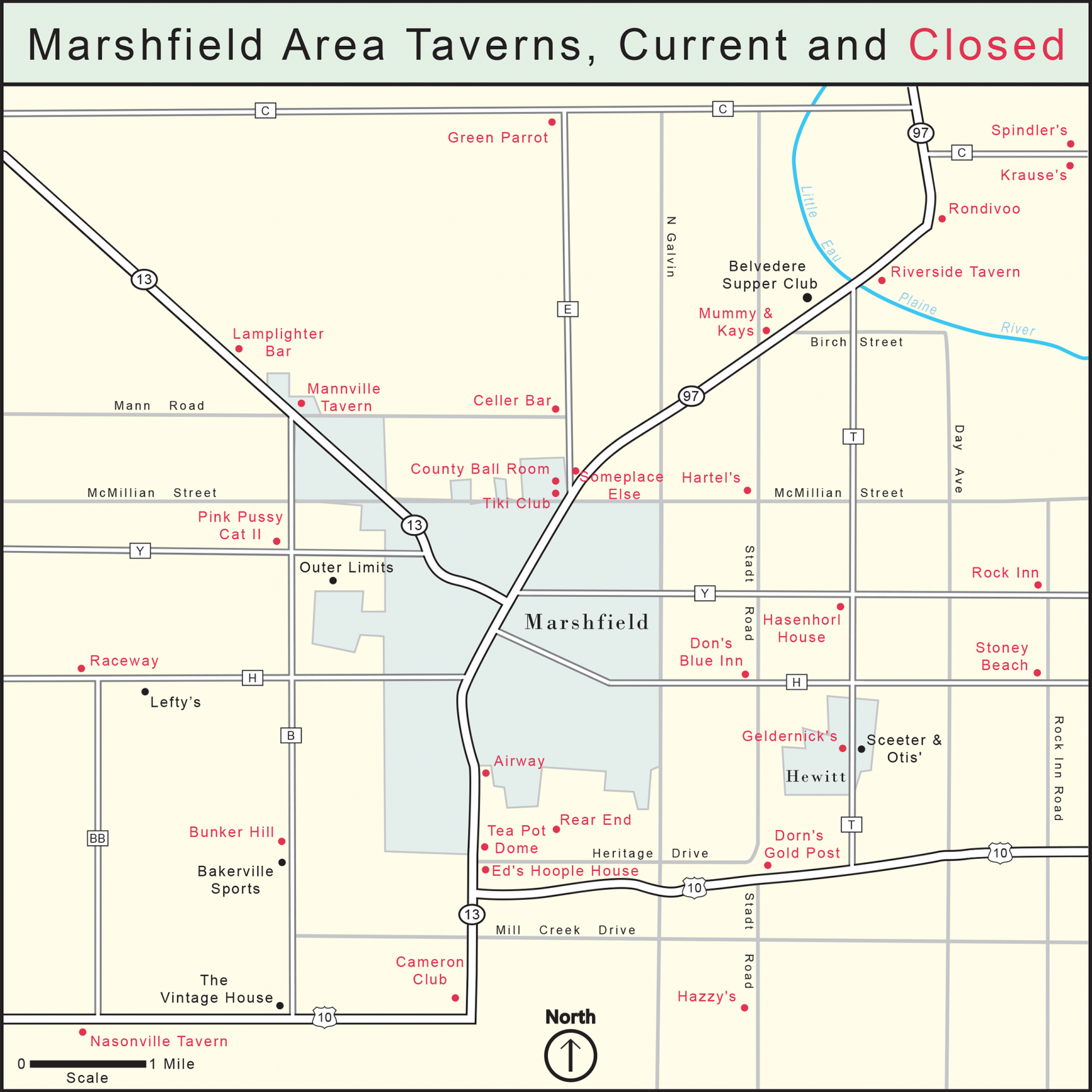

By the 1960s and 1970s, several dozen rural taverns were located within a 7 mile radius from the center of the city of Marshfield. Though many taverns may have had some level of food service, many were strictly drinking establishments. But by the end of the 20th century, more than three-fourths of Marshfield's rural taverns had closed their doors.

Today, those drinking establishments that remain around Marshfield also serve as restaurants and/or as outlets for sports entertainment like volleyball and cornhole. Only one rural tavern in the area (Lefty's) remains open as a purely drinking establishment, yet it also takes advantage of proximity to a race track.

Between 1960 and 2016, at least 29 taverns closed their doors. The 1980s saw the largest number of closures, at nine. Twelve of the taverns either burned down, were torn down or were simply abandoned. Eleven were renovated into housing, while five buildings are used for some other function.

The Tavern League of Wisconsin noted that while the state had over 15,000 taverns in the mid-1990s, that number had dropped to near 11,000 by 2016. This disappearance of rural taverns represent a major transition in the work and recreation culture of rural communities throughout the the state.

The closures of taverns around Marshfield have left lasting imprints on the landscape. Some have been demolished while others have changed appearances, with only stories from vanishing patrons holding their secrets. In the end, all of these taverns provided rural residents a familiar and positive place to meet and speak with neighbors, friends and family.

Specific reasons for why each tavern closed are not known, but in general, rural areas across Wisconsin saw similar declines based on several reasons, including shifts in the agricultural industry and urbanization.

By the 1990s, consistently low real milk prices and increasing farming costs led to the closures of many family farms. Close to town, land was sold to developers to provide housing for the growing medical workforce associated with Marshfield Clinic. Over time, traditional connections to the rural landscape gave way.

Marshfield and its surroundings straddle the border of Wood and Marathon counties. According the U.S. Census of Agriculture, from 1964 to 2017, both counties saw steady declines in the number of farms and farmers. In 1964, Marathon County had 4,629 farms — that number declined to 2,237 in 2017. Wood County was at 1,921 in 1964,and dropped to 1,062 in 2017. Consequently, this decline in farms led to a decrease in the number of farmhands. These farmhands, according to one former tavern owner, made up many of his patrons.

Changes to drunk driving laws and in the drinking age also affected the clientele of rural taverns.

In the 1980s, organizations like Mother Against Drunk Driving helped focus pressure to enact and enforce laws against driving while intoxicated. By 2001, Wisconsin shifted its Blood Alcohol Concentration limit for drivers from 0.10 to 0.08.

Interviews with local residents around Marshfield found it was common for tavern patrons to visit several taverns in one evening. With stricter enforcement and stiffer penalties, interviewees said these deterrents discouraged the practice of traveling to multiple establishments during a night out.

In one interview, a former patron said he knew of a rural bar (not in the immediate Marshfield area) that closed its doors because the local sheriff's office placed officers across the street from the establishment. They said patrons were too fearful of tickets and would not risk the drive into the country. Decreased patronage of this establishment led to the abrupt closure of this rural tavern. Today, it is a church.

Another factor in the decline of rural taverns (and urban taverns for that matter) was a change to the legal drinking age. In 1983, Wisconsin’s drinking age was changed from 18 to 19 and in 1986, with pressure from the federal government related to highway funding, it was again increased to 21.

A former purveyor of one tavern said it was common for younger people to frequent his rural establishment (much like their parents), but with changes in the drinking age, these patrons became more interested in frequenting bars in the city with their peers.

But the number of bars within the city of Marshfield also decreased over this time period. Former Marshfield mayor and tavern owner, Marvin Duerr, indicated in an interview that in the mid-1980s the city had about 40 bars. Today, that number is down to about 15 or so.

Both rural and urban bars saw operating costs increase coupled with dramatic decreases in patronage. Likewise, alcohol became easier to purchase in grocery stores and gas stations. Many rural homeowners drive to work in the cities, stop at a grocery store on their commute, purchase alcohol, and consume it at home.

Long gone are the days of the local drinking hole as a place to talk with neighbors. Today rural taverns, to stay solvent, have had to reimagine themselves by diversifying their revenue sources with food and/or entertainment as the major draw. For example, Bakerville Sports Bar & Grill built an indoor facility around the turn of the century that can host a variety of activities year-round like volleyball, or can be rented for several other indoor purposes.

The tavern as a destination may not be as visible or accessible in the rural landscape as it once had been, but it is not gone. At the same time, in no cases have any new rural taverns been built in the rural areas around Marshfield in recent years, and those remaining taverns have been in business for decades.

Though costs have increased for both consumers and purveyors, while drunk driving laws have become somewhat tougher, alcohol is more readily available today than ever. The consumption of alcohol has not left the rural landscape. Neighbors still interact with each other, but these interactions take place on decks, porches, yards, and in basements. The only question with this new rural drinking arrangement: Who brings the beer?

Editor's note: The article was reported in collaboration with Wisconsin Public Radio for its "High Tolerance" series, which explores the state's complicated relationship with alcohol.