Making Sense Of Special Elections In Wisconsin

When debating Gov. Scott Walker's decision to not call special elections to fill two vacancies in the Wisconsin Legislature, state political figures and commentators have argued over the move's implications for elections law, public spending and democracy itself. But what about precedent?

American politics in the 21st century is replete with policies capable of reshaping the very nature of representative government — a loosening of campaign-finance regulations, voter ID laws that can deter eligible voters, and sophisticated computer-aided partisan gerrymandering. Especially during the Trump era, a growing amount of national discussion has revolved around political norms. These are practices and guidelines that may not be firmly encoded in law, but are generally held to be important for participatory, representative government and the integrity of American political institutions. Are there political norms surrounding legislative special elections in Wisconsin, and if so, is Walker's move a departure from them?

One important element in Wisconsin's two legislative vacancies in 2018 is the sheer amount of time involved. Republican legislators Frank Lasee and Keith Ripp resigned their seats effective Dec. 29, 2017, to take jobs in Walker's administration. Since the governor has not called a special election, the next chance for Wisconsin voters to select representatives for state Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 will be in the Nov. 8, 2018 general election. Moreover, the new legislators will not be sworn until January 2019. This leaves the two seats empty for a little over a year. Is that normal?

The natural place to look for answers to these questions is in the state of Wisconsin's historical records of legislative vacancies and special elections. The Wisconsin Elections Commission has readily available online records that go back to 2000, and includes information about special elections. Gubernatorial executive orders going back to the administration of Gov. Patrick Lucey in the early 1970s are also provided online by the Wisconsin Legislature, and some of these were used to call special elections.

However, to get a clearer picture of special-elections history in Wisconsin requires more digging and piecing-together of government records. WisContext was told that neither the Elections Commission nor the Legislative Reference Bureau keeps comprehensive records that compile legislative vacancies or special elections into a single place.

WisContext also found evidence that earlier governors would call special elections through proclamations that technically were not executive orders. What about data on how long legislative seats stayed vacant after a legislator's resignation or death, or how long governors usually waited to call elections to fill their seats? If the state has such information, the eminently helpful staff of the Legislative Reference Bureau and Wisconsin Historical Society weren't able to dig it up. Reference librarians at the society told WisContext that many pre-Lucey executive orders are scattered among different collections of preceding governors' papers, and aren't easy to access in one place.

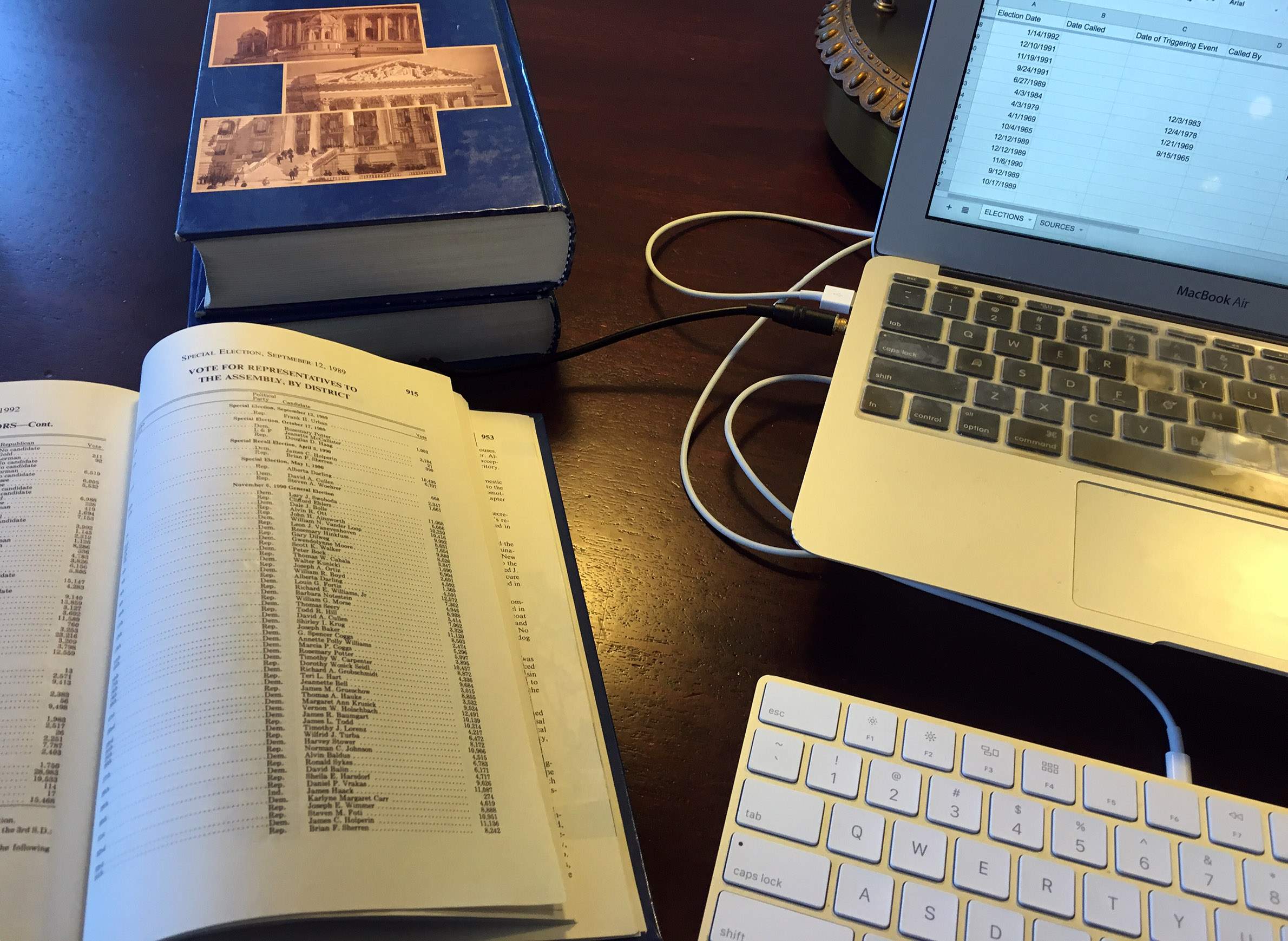

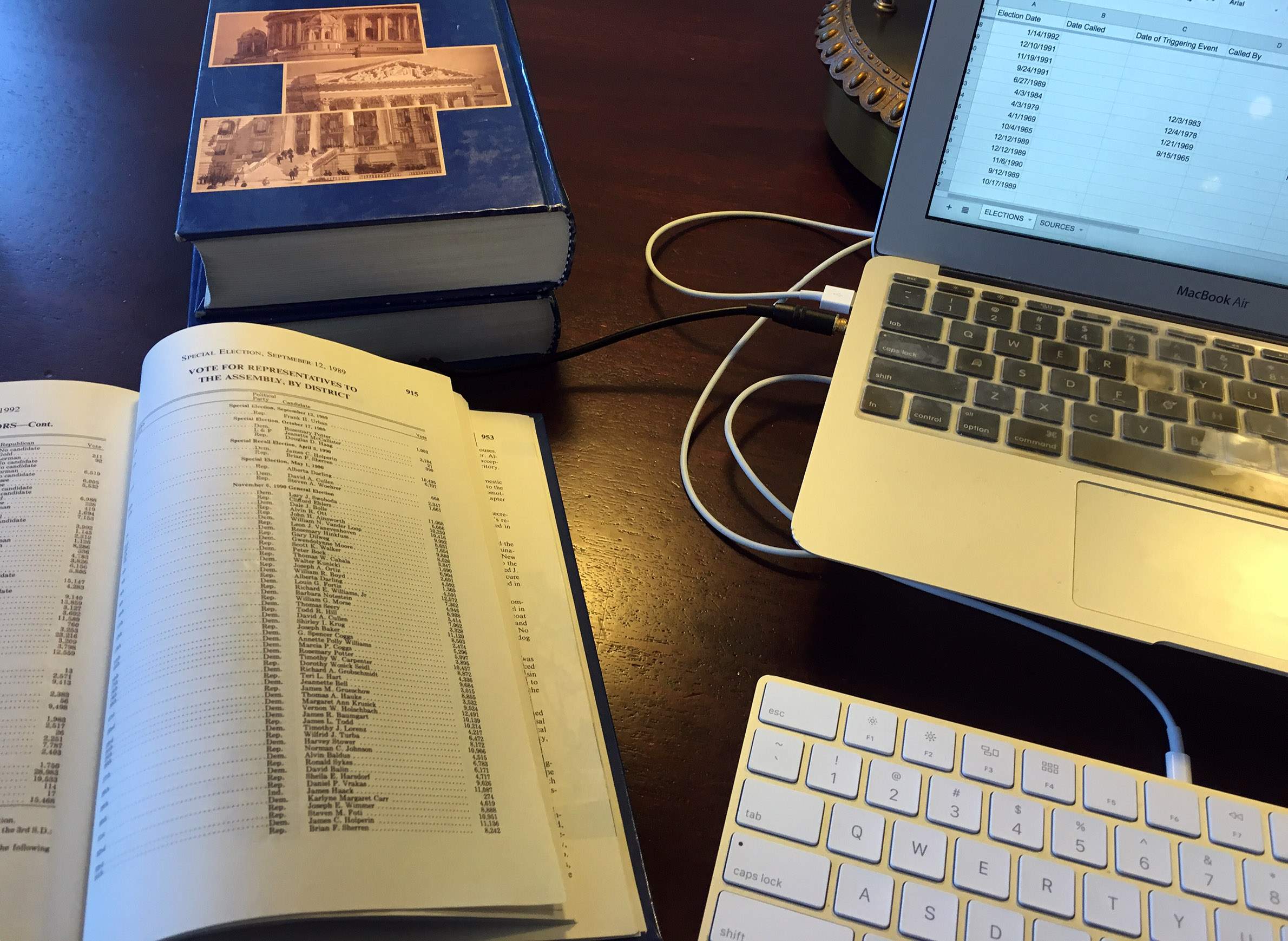

The next logical baseline is in the Wisconsin Blue Books, the official state-government reference volume for officials and the public alike. Blue Books include a list recent elections and their results, including special elections. WisContext did find the dates of most special elections in executive orders that called them going back to 1971 (when Lucey took office), but checking Blue Books from the early 1970s onward added helpful redundancy to the search and provided verification. WisContext referred to both sources to confirm that special election dates found in one source checked out with the other.

WisContext also needed to figure out when governors called special elections. Finding these dates was relatively easy, though, because the answer is in the dates of the executive orders.

Determining when a legislative seat became vacant, though, is a multi-layered problem. If a legislator died in office, it was easy to pin down their date of death in the journals of the Legislature (another reference source compiled by Legislative Reference Bureau), and double-check it against news reports of the time. If they resigned to take a different position, seek higher office or had to leave office amid scandal, pinning down an exact date is more difficult

Say an Assembly representative gets elected to the state Senate. Which date most accurately reflects when the vacancy in that Assembly seat began? The date of the election in which they won the Senate seat? The date on which they were sworn into the Senate? The date on which they formally resigned the Assembly seat?

To the greatest extent possible, WisContext used the date on which a legislator's resignation became effective. Sometimes this date is given in executive orders calling for special elections, but governors have not been consistent about this. The journals of the Legislature do list dates of resignations, and sometimes include records of the formal resignation letters legislators submitted, which will usually note an effective date. At times, though, this information was elusive and WisContext determined the most concrete date available relating to the events that would have triggered a vacancy.

In the interests of transparency, and in case it's useful to the public, journalists or researchers, WisContext is making available data it assembled about Wisconsin's legislative vacancies and special elections between 1971 and February 2018 for anyone to consult.

Outside of the state of Wisconsin's official records, WisContext found there has been very little research into the role of special elections in state government, in Wisconsin or elsewhere.

Kenneth Mayer, a University of Wisconsin-Madison political scientist has taken part in a few high-profile studies of elections in the state. In response to a query about scholarly research on legislative vacancies at the state level, he said in an email, "There is a small literature [about special elections], but all of it is about federal elections, not state (or about special elections in other countries — India, Liberia, and Israel), and they don’t have much to say about vacancies."

Mayer pointed to a 1999 paper titled "What Is So Special About Special Elections?" It indeed seems to be one of very few academic papers that focus specifically on special elections, and in this examines special elections for Congress and how they're perceived as referenda on the sitting president at the time.

The question of state-level legislative vacancies, and how governors use their power to fill them, certainly appears to be little studied. It's a highly specific facet of state-level politics, but state legislatures and governors make decisions that have profound impacts on people's lives and on national politics. A more complete record would help Wisconsinites better understand any argument over special elections in the state. WisContext was surprised to not find more comprehensive sources detailing this aspect of Wisconsin political history.