When Big Storms Inundate Wisconsin, How Could Wetlands 'Slow The Flow'?

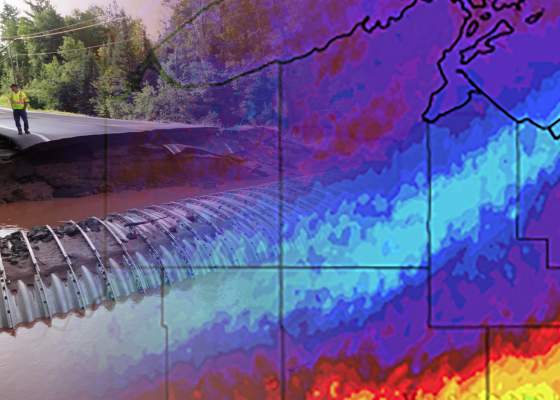

When record-setting rains in July 2016 sent murky, sediment-laden floodwaters rushing into Chequamegon Bay, residents of Ashland and other bayside communities on Lake Superior's south shore were provided with a stark visual reminder of just how much the region's streams and rivers impact the world's largest body of freshwater.

What may have been less clear — yet was critical for understanding how the flood unfolded — was the connection between those rivers conveying the muddy water and the wetlands that help feed them.

That connection has become increasingly tenuous over the last century-and-a-half, as the degradation and loss of rain-soaking wetlands in the Lake Superior basin has fundamentally altered the path and velocity of water gushing toward the lake. While this disconnection continuously affects ecosystems and wildlife, its consequences for human communities come into clearer focus when heavy rains transform these same streams and rivers into forces of wanton destruction.

That's what has occurred on a large scale in northwestern Wisconsin at least three times since 2012, as extreme storms caused rivers and streams to quickly rise and wash away tens of millions of dollars worth of infrastructure. Proponents of restoring wetlands say these destructive forces can be weakened, but doing so requires buy-in from landowners and local governments, with a strategic focus on high-impact smaller-scale projects.

Restoring wetlands in Ashland County

Officials in Ashland County are gearing up for a pilot project in the Marengo River watershed that could serve as a proof of concept for low-cost wetland restoration as a natural flood-control measure. The county was received verbal approval for a $200,000 from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to develop cost-effective concepts toward that end. At the same time, a bipartisan bill moving through the state Legislature would provide $150,000 to fund three demonstration sites based on those concepts.

How water flows through the Marengo watershed has long been a focus of natural resource managers. The river winds through Bayfield and Ashland counties and drains into the Bad River, which reached record flow levels during the 2016 storm that turned the waters of Chequamegon Bay a creamy reddish-brown color. The same system caused more than $36 million in damage to public infrastructure across a seven-county region.

The upper part of the Marengo flows through sandy soils, but its lower portion is dominated by clay soils that don't drain well and easily erode. Historically, wetlands in the river's upper watershed would have kept some portion of the water that falls in large storms from running straight into the river, but now it can quickly rise to flood stage even during less catastrophic events.

Compounding the problem in the Marengo and other rivers is how faster moving waters, at and below flood stage, are altering the riverbeds themselves. The quickly moving water carries more energy than it did in the past, eroding stream banks and carrying higher sediment loads. This is detrimental to wildlife, including native trout, and can also cut rivers off from wetlands within their floodplains, further degrading those wetlands. Large, permanently flooded wetlands located downriver, such as those near the mouth of the Bad River on Chequamegon Point, are beneficial in many ways, but they're little help in mitigating flash flooding upstream.

Massive flooding and loss of infrastructure in 2016 and a subsequent storm in 2018 prompted the Marengo project, said MaryJo Gingras, who heads up Ashland County's Land and Water Conservation Department. Damage from 2016 storm within the watershed ran in the millions of dollars, she said, and climate models project more frequent storms of that magnitude for the region's future.

"That prompts a question: Okay, how do we adapt or how do we be more resilient in the future if these are going to be more commonly occurring events," said Gingras. "It's not just a matter of fixing roads and bridges that were damaged if we are going to see the same results. It involves proactive planning and asking ourselves 'What do we do on the landscape so we don’t have this destruction in the future?' Part of that is looking at areas that can hold and store water. The biggest thing we're trying to do is slow the water down."

Gingras said the county has historically followed the lead of landowners who want to restore wetlands on their private property. Now she hopes this more proactive and targeted approach can provide a roadmap for planners in other communities in Wisconsin and beyond.

"We've never seen this type of project in this state," she said. "This could provide some really good information and tools that could be used in other areas that are also really prone to floods and infrastructure damage."

Wetland losses statewide

The loss of high-quality wetlands extends well beyond the Northwoods, touching every part of Wisconsin. Since intensive farming and logging began in the mid 19th century, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources estimates the state has lost about half its wetlands. Over the course of a century, according to these estimates, more than 5 million acres of swamps, shallow ponds, wet meadows and seasonal forest bogs were filled or drained to make way for urban and suburban development and economically productive land uses, primarily agriculture.

The DNR first catalogued the state's wetlands via aerial photography in the 1970s, following up with more targeted surveys in many counties over subsequent decades. The data are amassed in the agency's wetlands inventory, which provides a broad understanding of the wetland acreage estimated to be remaining in all of Wisconsin's 72 counties. The DNR estimated losses based on soil-type information rather than historical surveys from the 19th century, which it considers to have massively underestimated wetland acreage.

The agency has not responded to specific questions from WisContext about these loss estimates.

Wetland losses have slowed in recent decades. In 1991, Wisconsin became the first state in the nation to regulate its wetlands under the federal Clean Water Act. The regulations have made it more difficult to fill or drain wetlands, but in doing so they've also made wetlands a source of controversy among developers and landowners.

The losses are more severe in southern Wisconsin, where they can reach as high as 80% in some counties, according to Kyle Magyera. His work for the Wisconsin Wetlands Association, a nonprofit that advocates for protection and restoration of wetlands, includes helping local governments with restoration projects.

"No matter where you are in the state, most of our wetlands are degraded," Magyera said.

Magyera explained that a large portion of the lost and degraded wetlands are the type found in upper parts of watersheds. They are often small and scattered and don't resemble the stereotypical wetland of shallow waters with lily pads and cattails. Instead, they're often found in forests and appear dry much of the time, he said. Historically, they were viewed as a barrier to development and fairly easily dispatched by farmers and loggers.

Wetlands in many floodplains are also increasingly degraded and cut off from water sources as erosion cuts deeper riverbed channels. The result is that wetlands of varying types throughout watersheds are not providing the water-storing function in the way they once did.

"They've lost their water source," Magyera said. "Or their ability to intercept water and hold it back and provide those water management functions that are critical to providing clean water, to slowing the flow and to protecting infrastructure."

"Slow the flow" has become a widely used mantra of wetlands proponents. The pithy catchphrase sums up how effective wetlands work: By infiltrating large amounts of rain and slowly releasing it into ground and surface waters, wetlands literally slow the velocity (and reduce the volume) of water in streams and rivers. As such, wetlands are increasingly cited as a crucial tool, if not a panacea, for mitigating the impacts of extreme rain.

"The big storms will keep coming," said Erin O'Brien, policy programs director for the Wisconsin Wetlands Association. "The question is: 'Is all this massive flooding just inevitable and there's nothing we can do about it, or can we actually heal our hydrologic systems to the point where the land has a greater capacity to handle the water?'"

Still, O'Brien and her colleagues say that expanding and improving wetlands in all parts of watersheds, especially in uplands and floodplains, could significantly reduce flooding and the millions of dollars in damage it can cause. And, they say, doing so strategically, such as what is proposed in the Marengo watershed, can be cost effective.

O'Brien firmly believes that expanding wetlands can help achieve climate resilience, though she was careful to say that wetlands are not on their own going to stop flooding.

"There's no one fix," she said.