Reengineering Infrastructure For A Wetter Wisconsin

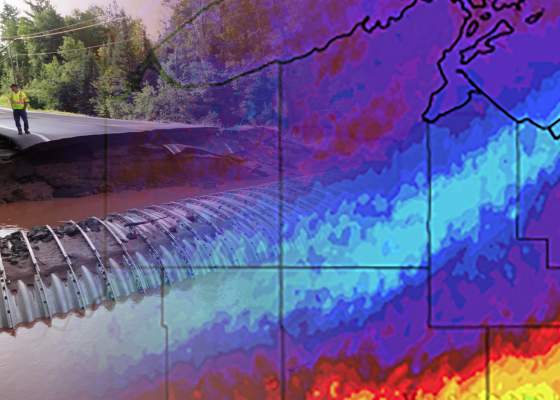

Flooding throughout the Midwest, including Wisconsin, is dangerous, costly and becoming a more frequent occurrence. Over the last few years, bridges and roads have washed away during flash floods in the northern part of the state, and in places like Madison, floodwaters took weeks to recede after heavy rainstorms in 2018. But how can engineers tackle the problem in order to prevent this kind of infrastructure damage in the future?

Daniel Wright is an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His areas of research include extreme rainfall and its effects on flooding, modeling the potential effects of heavy precipitation in different landscapes, and projecting the role of climate change in these risks. Wright is also working with colleagues in the Wisconsin Initiative On Climate Change Impacts in an infrastructure working group to develop approaches that take floods and climate change into consideration for engineering and planning purposes.

Wright spoke about these issues in a Nov. 1, 2019 interview with Wisconsin Public Radio's Central Time. The complete audio of this discussion follows, along with an abridged version of the conversation.

Rob Ferrett: People talk about things like the 10-year floods and 100-year floods, and I think people get confused when they hear those phrases. What do we mean by those terms?

Daniel Wright: I think the key point here for the public is just to understand that the larger the number, the more rare the event is. So a 10-year flood is going to be less severe, but happen more often than a 100-year flood.

But if our 100-year storm happens today, it doesn't mean we're off the hook for 100 years — it could happen tomorrow, too.

That's absolutely right. The analogy that I draws is to gambling in Las Vegas. Right. You never know what's going to happen on the next roll of the dice.

It feels like we're seeing intense storms happening more often, but maybe they're in the headlines lately, it's our perception that they are. Part of what you're looking into is are we seeing more intense rainfall, bigger storms? What do you see when you look at the data?

The data is pretty clear on this. Pretty clear in Wisconsin, in the Midwest and throughout the entire country that extreme rainstorms are happening more and more often. So, for example, we're seeing that what at least historically has been considered to be the 100-year storm in the eastern United States is happening almost twice as often now as it was in the 1950s.

Have we developed an infrastructure based on the old storm predictions that can't keep up with what's really happening now?

This is a huge issue that we're working on now in my research group at the University of Wisconsin.

The basic starting point for a lot of infrastructure design and infrastructure planning are these rainfall statistics such as the 100-year storm. So depending on what type of infrastructure you're needing to design, for example in the case of a stormwater pipe, it might need to be sized such that it could move the water associated with let's say a 10-year storm. But if you were designing a more critical piece of infrastructure like a bridge over a river or something like that, you might have to consider the 100-year storm or even 500-year storm.

Nowadays it's the National Weather Service that releases these numbers. The most recent update to these statistics came out, in this part of the country anyways, about eight or 10 years ago. And what we've found through analysis of more recent data is that, particularly in this part of the country, throughout the eastern U.S., that even those most recent numbers released by the National Weather Service are far behind where they need to be.

And so just an example of this is that what the National Weather Service says is 100-year storm in the upper Midwest looks to be something more between the 40- and 80-year storm. That means that any infrastructure that's been built according to that standard is much more likely to be overwhelmed than its intended design.

As you look at communities around the state, are we doing anything with our infrastructure to try to catch up with these new rainfall realities?

I think we're starting to. There's growing recognition, certainly amongst planners and engineers, that we need to start getting ahead of this problem. And so we're active in the university and also through what's known as the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts to help provide information to municipalities and other organizations to help them respond to this challenge.

We've just created a new infrastructure working group within the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, and this issue of increasing rainfall and flooding is one of the main focuses of that working group in the near term. We're working on producing new statistics, putting together a network of professionals from around the state to help see how we can integrate those statistics into new engineering practices. And then also by bringing that group together, different folks from around the state can share experiences and help find ways that we can all move ahead on this problem.

I wonder if there's a mindset issue here. I think a lot of people, I'll include myself, think of flooding as a "natural" disaster. Is it the case that a lot of things that we see, these floods that have happened, if we'd had a better infrastructure that was more up to speed with, again, this rainfall reality we have now, there would've been a heavy rain, but it wouldn't have been a flood event?

It's a mix of both issues.

Certainly extreme rainfall and floods have always happened long before Madison and other parts of the state were developed. When we have the types of rainfall that we had here in the Madison area last August, where we had upwards of 15 inches over six or eight hours, it's going to be really difficult to design infrastructure that can withstand that type of storm.

On the other hand, what we're seeing is that you don't these days need nearly that much rainfall to cause really serious problems. That's because of a combination of undersized stormwater and flood management infrastructure combined with all of the urban development that's going on ... that reduces the environment's capacity to soak water into the ground and move it downstream slowly. And the reduction of the number of wetlands and things like that in a natural environment helped to store some of that rainfall and slow down its movement through the environment.

With that in mind, I'm sure there's no one-size-fits-all approach that's going to help prevent floods in every community. That said, is there a laundry list of things that communities can consider as they try to update their infrastructure?

That's part of the objective of starting up this infrastructure working group in the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, is to try to figure out are there common themes that different communities around the state are facing? Because you could imagine that smaller communities in northern Wisconsin, for example, are facing a very different set of realities, both in terms perhaps of the storms, but also the availability of funding and whatnot as compared with Madison or Milwaukee. And so I'm not sure that we have that laundry list of solutions yet, but that is definitely where we're trying to head over the next year or so.